The necessity of banding together and communicating in order to achieve a shared goal is profound. ‘The Commons’ is a broad term which refers to any resource shared by a group of people. In her writings about the Commons, economist Elinor Ostrom analysed how people come together when there is a need to distribute resources in a manner that is equitable, efficient, and sustainable. She identified several principles needed for good governance of shared resources, including clearly defined, enforceable boundaries which meet the needs and conditions of the affected individuals.

People must feel that they have a voice in the creation of these rules and that they can participate in changing them.

The view that we are incapable of correctly distributing shared resources without an overarching governing body – an idea referred to as ‘The Tragedy of The Commons’ – has prevailed within the structures which guide our lives, such as workplaces and national governments (including democracies). Without top-down governing bodies, it is widely believed that people will work against the interests of the collective.

The exhibition Common has multiple entryways, initially found in process towards other projects at A4. The first is through research about independent initiatives by emerging artists and practitioners, and a desire to account for the exhibition models and experiences produced within the local ecosystem. The second entryway is via an anecdote that was shared in conversation with artist Unathi Mkonto. His family had come together for a funeral and, because of limited space, and the number of attendant guests, the marquee for the gathering was installed over the wall of the yard so that the crowd was split into two. One’s place in the familial and social hierarchy determined one’s seating position on one or the other side of the wall. This struck me as a relatable obstacle to the Commons.

Common explores new and longstanding models of self-governance and collective action. Expanding beyond the realm of economics – ‘the Commons’ is usually used to address ecological concerns such as forestry and water management – the exhibition takes an intimate approach to collective action, highlighting relatable forms of organising which are often taken for granted. These forms are as localised as a family refrigerator, weddings, and protest groups – and as expansive as liberation movements, the art world, and online information sharing. Though they may seem disparate, these examples demonstrate the variety and omnipresence of organisational structures in our daily interactions. By unpacking and magnifying the experiences and emotional responses evoked by varying forms of collective action, Common seeks to explore how people perceive themselves within these structures, and how we can better prioritise trust, reciprocity, and sociability.

Family as organisational structure

Sue Williamson, Guy Simpson, Sabelo Mlangeni

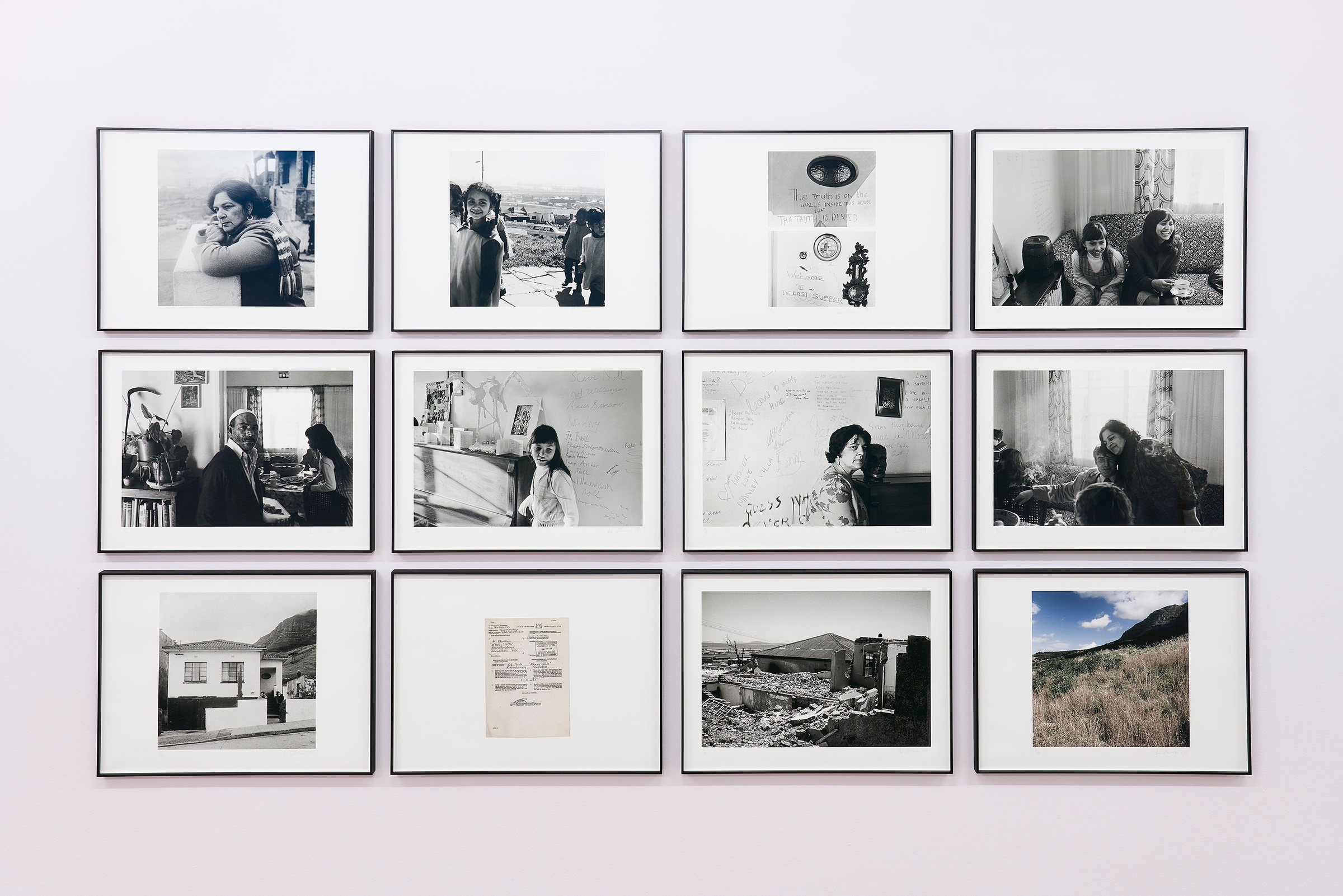

The most relatable – and widely defined – organisational structure is the family unit. The exhibition begins with Sue Williamson’s The Last Supper at Manley Villa (1981/2008). The series of photographs documents the Ebrahim family’s last Eid celebration in their District Six home before being forcibly removed by the apartheid government. The first ten images of the series were taken on or around 2 August 1981, showing a family at peace in the comfort of their home. The last two photographs show the remnants of their home. One was taken a few months after Manley Villa’s destruction, made visible in the remaining rubble. The final image shows the site of removal almost two decades later. Here, there is no sign of the act of violence or the harmonious structure that preceded it. In its place is an expanse of scenic green space. The beauty of nature is often used by colonialist governments to mask and justify the destruction of preexisting communities.

The inclusion of fourteen photographs from Sabelo Mlangeni’s Isivumelwano series (2003–2020) continues the exploration of family as an organisational structure.

As set out in Ostrom’s principles of a well-run commons, boundaries should not only be clearly defined, but the people affected by these boundaries should be able to participate in modifying them.

The title of the series can be translated into English as ‘agreement’ – a word which can be interpreted as referring to informal consensus amongst a group, or a formal process of defining the boundaries between two or more people, which acts as a social (or legal, or customary) contract. Marriage is the primary tool of shifting boundaries within the family (alongside divorce).

Wedding photography centres on sentimentality, a quality which is ranked low within the Western hierarchy of aesthetic value. Mlangeni subverts this understanding of the genre by pairing sentiment with challenging compositions. Neutral, candid facial expressions and veils of shadow create a sombre tone and a sense of anonymity, which is uncommon in a wedding picture, placing the rituals which surround weddings above the subjectivity of the brides and grooms. However, he does not fully rely on the critical, impersonal lens of the documentary photographer. The moments he has captured often feel deeply intimate, such as Umkhongi, the chief negotiator (2020), an image of a male family member sleeping on the floor during the process of negotiating lobola (translated in English as ‘bride price’ or ‘bride wealth’).

Marriage is a mechanism of sharing wealth among immediate family, while weddings cast a wider net to the community at large. This intention drives the ubiquitous inclusion of the multi-tiered wedding cake, marquees, buffet tables, and event chairs draped in white fabric, all present in the images. They are a visual expression of an organisational form, intended to create an impression of plentiful resources and generosity.

Archives of collective action

GALA Queer Archive, SAHA, The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember

Central to the exhibition are organisations which have enlivened the archive by including ephemera which highlight the sensations associated with collective action. The GALA Queer Archive and the South African History Archive have contributed a small selection of the many T-shirts in their care, made for specific protest actions.

While many of the T-shirts prioritise message over visual impact, there are also many which clearly express the creativity and care of their makers – a reminder of the essential work of cultural workers like Judy Seidman and Thamsanqa Mnyele.

The selection of T-shirts contributed to the exhibition by the South African History Archive (SAHA) are a visceral response to inequitable access to the country’s resources. Labour unions and community groups as large as the National Union of Mineworkers and as small as the Queenstown Residents’ Association are represented. Their slogans show the struggle for basic resources: housing, living wages, safe working conditions, freedom of movement, and the right to gather. They reiterate the need for collective action, placing persistent emphasis on words like ‘we’ and ‘us’, ‘unity’, and ‘mobilise’, and phrases such as “each one, teach one”.

The T-shirts in GALA’s collection show the struggle for equitable access to safety and tolerance as resources. The context of ideological and physical violence against LGBTQI+ people which has forced them to hide their sexuality or gender – an innate part of our sense of identity – makes the T-shirts particularly affecting. Groups like the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of Witwatersrand (GLOW) and the Organisation of Lesbian and Gay Activists (OLGA) gave their members the ability to wear their hearts on their sleeves with ferocity and humour, through slogans like “Marriage: anything less is not equal” and “Closets are for clothes, not people”.

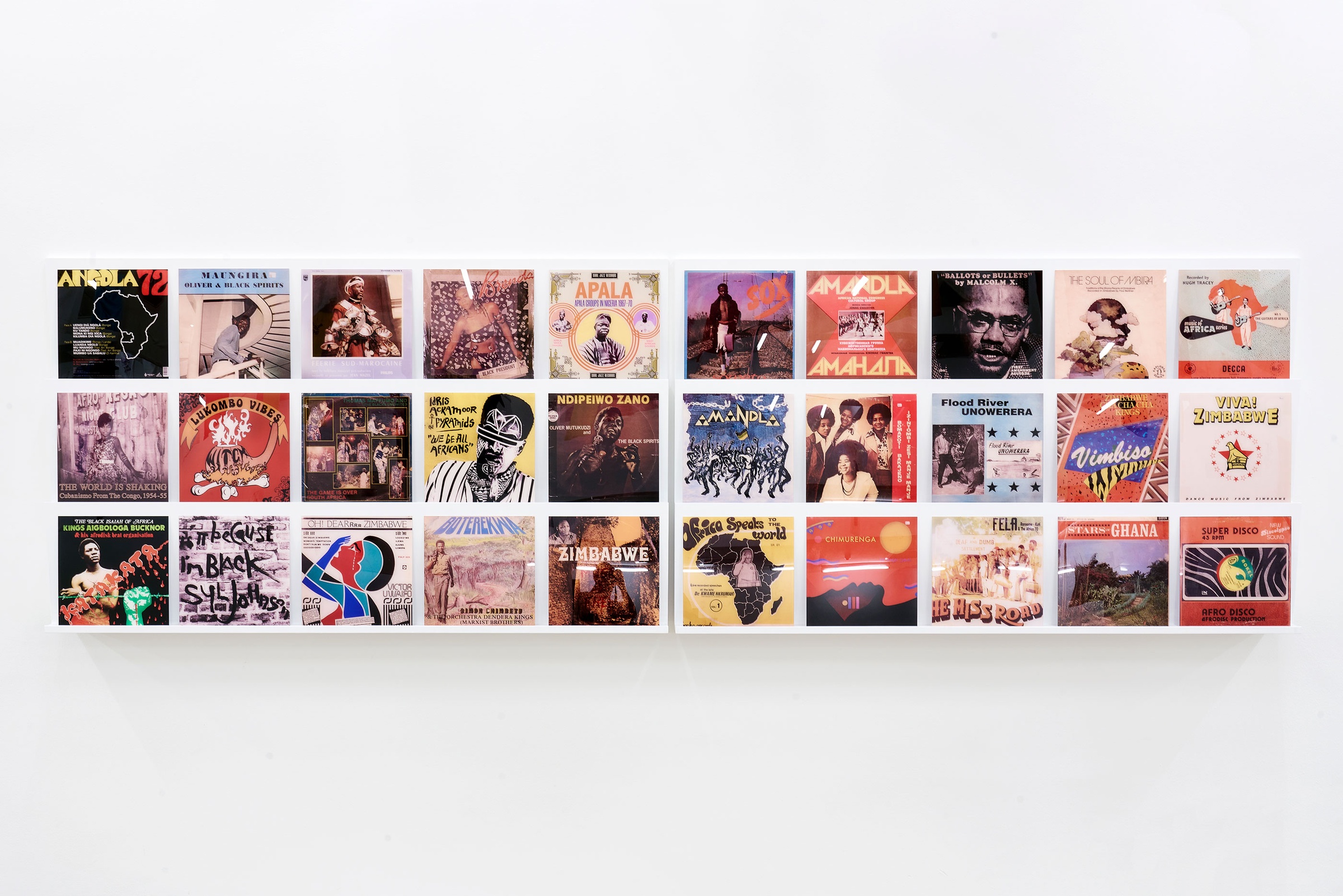

The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember expands the exhibition’s view to collective, political action throughout Africa. This exhibition focuses on The Library’s vinyl record collection. Most of the vinyls were produced between the mid- to late-twentieth century. They were the soundtrack to the continent-wide struggle for freedom and a further example of the contributions of cultural workers to liberation movements. Though they do not all include explicitly political messaging, their references to folk traditions of African music were inherent acts of resistance to colonial governments.

Gerard Sekoto’s The Milkman (1945–47) and George Pemba’s The Agitator (1960) both make use of their own interpretations of social realist painting, to different emotional ends. The golden light and long shadows of The Milkman imbues it with sentiment despite the poverty of the people, seen bare-footed amongst the rudimentary forms of township houses. The composition places emphasis on the mechanism they use to distribute food within their community, rather than their individual experiences. The milkman, who is ostensibly the central figure, is mostly faceless and grouped together with his customers. In The Agitator, the protagonist (or antagonist) is more clearcut. The audiences’ faces are a blur of abstracted brushstrokes. We see the potential influence of an individual over a group.

Information sharing and knowledge as commons

Fabian Saptouw, Mark Bradford, Hanna Noor Mahomed, The Library of

Things We Forgot to Remember

Knowledge is cumulative. With ideas the cumulative effect is a public good, so long as people have access to the vast storehouse – Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom. 1

The Commons was initially used to understand how best to distribute and maintain natural resources which are finite and therefore need to be sustainably managed. Knowledge is an unusual resource because one person’s use does not exclude its use by others, and greater access fuels greater knowledge production.

Fabian Saptouw’s ISBN Portrait Series (2015) gives a ‘face’ to the huge stores of knowledge held by the libraries of South African universities. Saptouw’s attempt to exhaustively record these codes was challenged by the bureaucracy which guards university archives, as well as the lack of software compatibility amongst different digital archive systems, and the fact that ISBNs were introduced in 1970, not capturing the many books which existed before, as well as publications which were informally produced.

Hanna Noor Mahomed’s painting, Google Docs (2022) depicts the online software’s icon. For many it is a symbol of productivity and collaborative processes. However its instant recognisability illustrates the growing monopoly on personal data and information held by tech companies like Google. The company assures users that they do not mine personal documents for data to sell to advertisers or government agencies, though this use of data from their search engine is integral to their business model. Given the ubiquity of Google’s software, it is plausible that a change in this policy would not deter most users away from their services. Privacy has been devalued in favour of technological conveniences.

Mark Bradford’s Life Size (2019) is an editioned rendering of a police body camera, used in the US. It brings to mind the social structures which have created an environment in which people of colour are murdered by police with little to no consequences. However, it is also an illustration of the power of online information sharing. Filmed footage of police brutality, shared widely on the internet, has validated African American experiences of the corrupt justice system which had been ignored for years, leading to widespread calls for police reform.

Boundaries

Nolan Oswald Dennis, Francis Alÿs, Guy Simpson, Lerato Shadi, Hanna Noor Mahomed

Nolan Oswald Dennis’ model to an endless column (2021) references Constantin Brancusi’s work of the same name, which he turned into a monumental outdoor sculpture in 1938. It is a visual illustration of infinity. For Brancusi, this was a symbol of the infinite sacrifice of Romanian soldiers during the First World War. Dennis’ sculpture shows infinite Earths, implying infinite resources. The impossibility of the model emphasises the finite nature of the world’s resources. Dennis has flipped the Earth, placing the southern hemisphere at the top of the globe - a reminder that the models we use to understand the world are a result of the cultural primacy of European cartographers rather than scientific necessity.

Conceptually, Guy Simpson’s Untitled (2023) acts directly in contrast with model to an endless column. Dennis’ work is a representation of infinity, which is near impossible to wrap one’s head around, while Simpson uses a relatable example of limited resources and their boundaries. A shared refrigerator, whether it is placed in the home or in the workplace, is subject to the boundaries of etiquette and the collective’s perception of fairness. The appliance’s familiar surface immediately gives rise to all of our personal anecdotes about the communications and miscommunications surrounding its contents.

In Painting/Retoque (2008), Francis Alÿs offers a more intimate interaction with boundaries imposed by overarching, dominating bodies. The video is set in the former Panama Canal Zone, carved out by the US to secure economic interests in South America via the Panama Canal shipping route. Alÿs carefully repaints the faded marking of a traffic boundary line with an artist’s brush, as locals continue on in the course of their daily lives, sometimes watching the performance with bemusement. The humour of Alÿs’s action and the contrast of his unchanged surroundings shows the arbitrariness of national boundaries.

Lerato Shadi’s Mabogo Dinku (2019) points to an opaque Setswana proverb, “Mabogo Dinku a a thebana” translated in English as “hands are like sheep, they help each other”2. Like this proverb, Shadi’s video documentation of hand gestures resists translation. Language is often explored for its ability to bridge gaps of understanding. This work demonstrates language as a fortress against the oppressive, colonial force of English translation.

In a discussion about the present lack of cultural workers’ groups, like the Community Art Project (CAP) in Woodstock and the Medu Art Ensemble in Gaborone, Sue Williamson suggested that it could be due to the ‘enemy’ being more diffuse. The people and organisations who contributed to the three archives represented in Common had clearly defined obstacles and objectives.

The contemporary art world often uses the language of radical, collective action but there is a wider context of individualisation and commercialisation.

There is also the understandable need to be an individual rather than only making work about one’s gender, sexuality, race, or economic class. Hanna Noor Mahomed’s wall mural, titled The Prodigal Daughter (2023), details the battle undertaken by young women artists of colour attempting to surmount the ambiguous boundaries, hierarchies, and rules of the art world, mediated through her own experience.

1. Hess, Charlotte, and Ostrom, Elinor. 2006. ‘Introduction’, Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: Theory to Practice, p. 8. The MIT Press: Massachusetts

2. Ramagoshi, Refilwe, 2016. ‘Stokvels in the African communities: this is how we do it’, Plus 50, Vol. 11, No. 4, p.51.