Sekoto: Home & Exile

Library Residency team

While in residence in the Library, Inga Somdyala, together with Khanya Mashabela and Daniel Malan, wonders about South African arts practitioners who left the country during apartheid, and the effects of exile on their understanding of home, belonging, citizenship, and national identity. – September 17, 2025

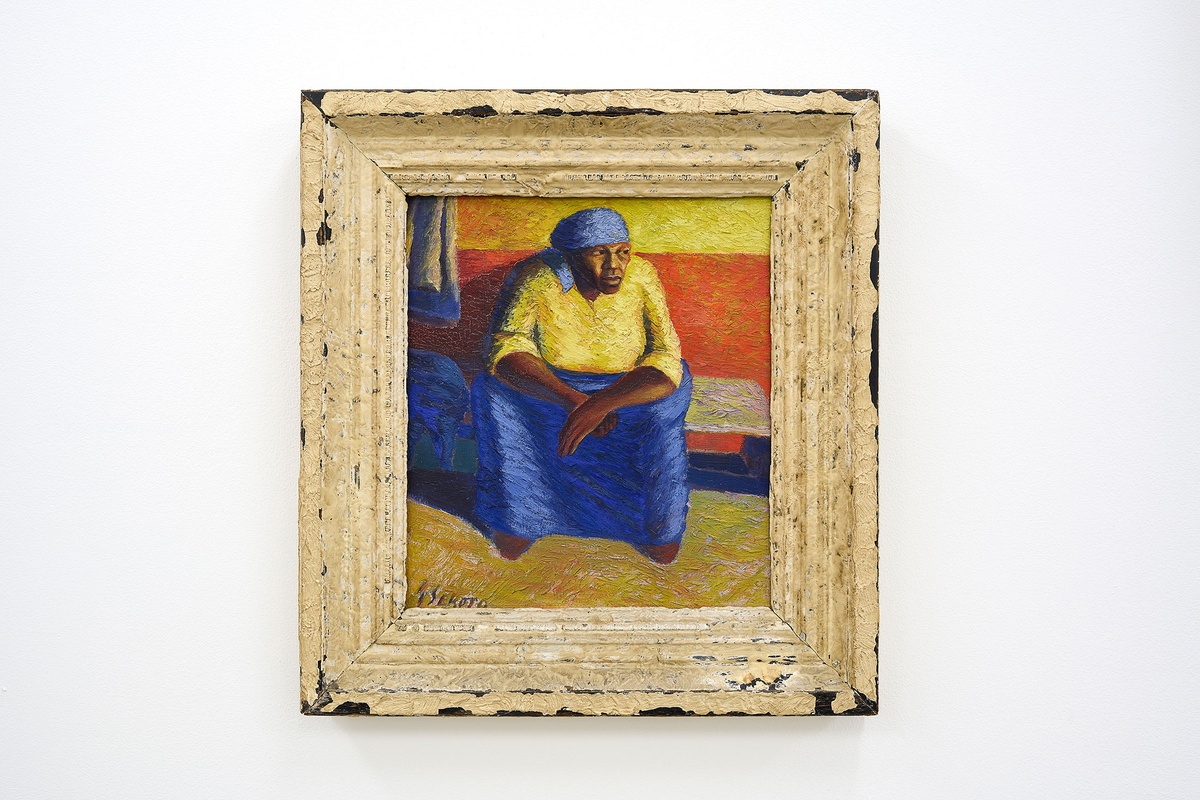

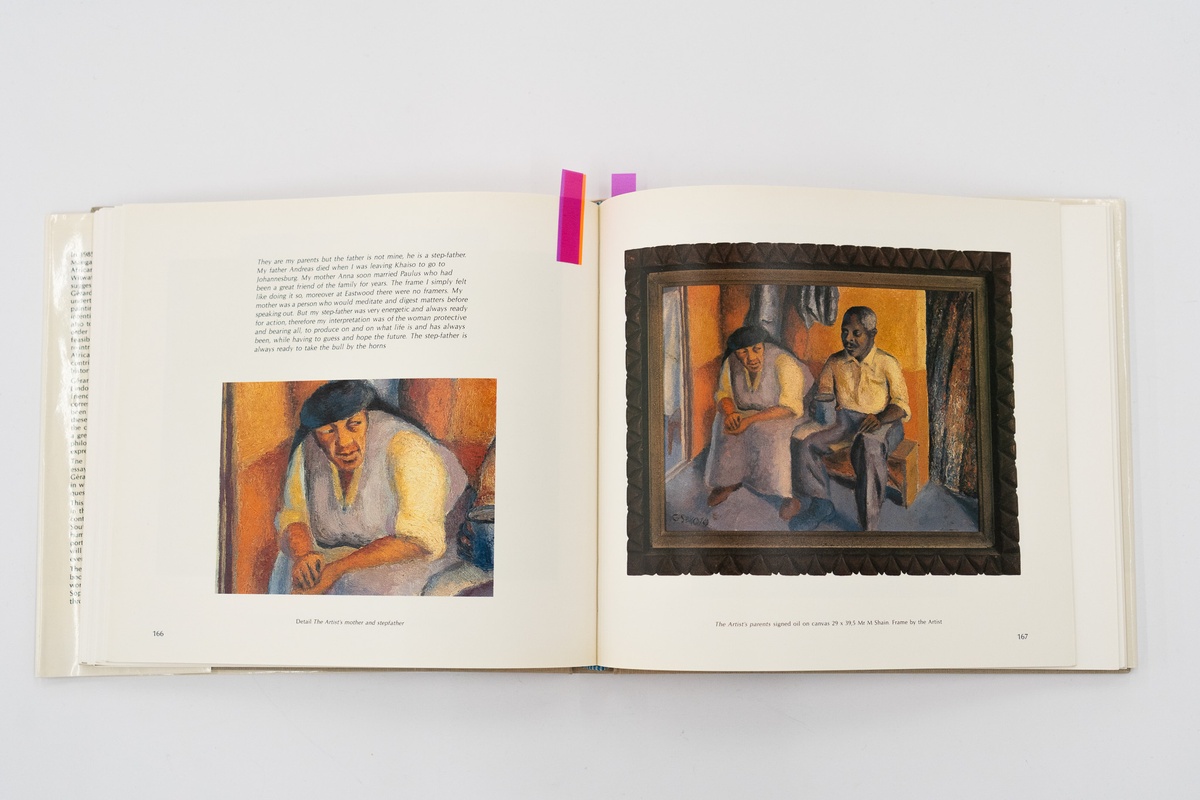

My mother was a person who would meditate and digest matters before speaking out. […] My interpretation was of the woman protective and bearing all, to produce on and on what life is and has always been, while having to guess and hope the future.1

– Gerard Sekoto

Gerard Sekoto sketched and reworked this same image of his mother – in variations of the same dress, seated on the same bench, in front of the same wall.Was he invoking home? Though Sekoto would have been living with his mother when he painted her portrait, he was away from his childhood home in Mpumalanga province.

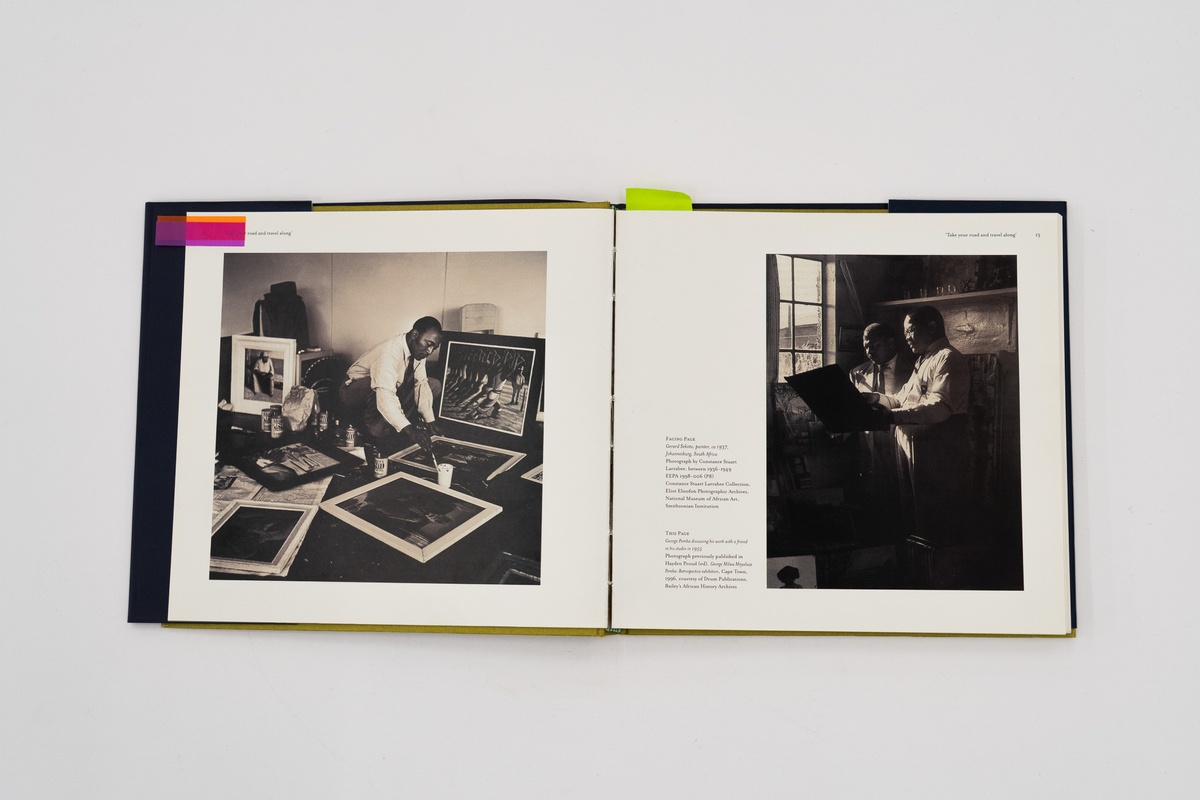

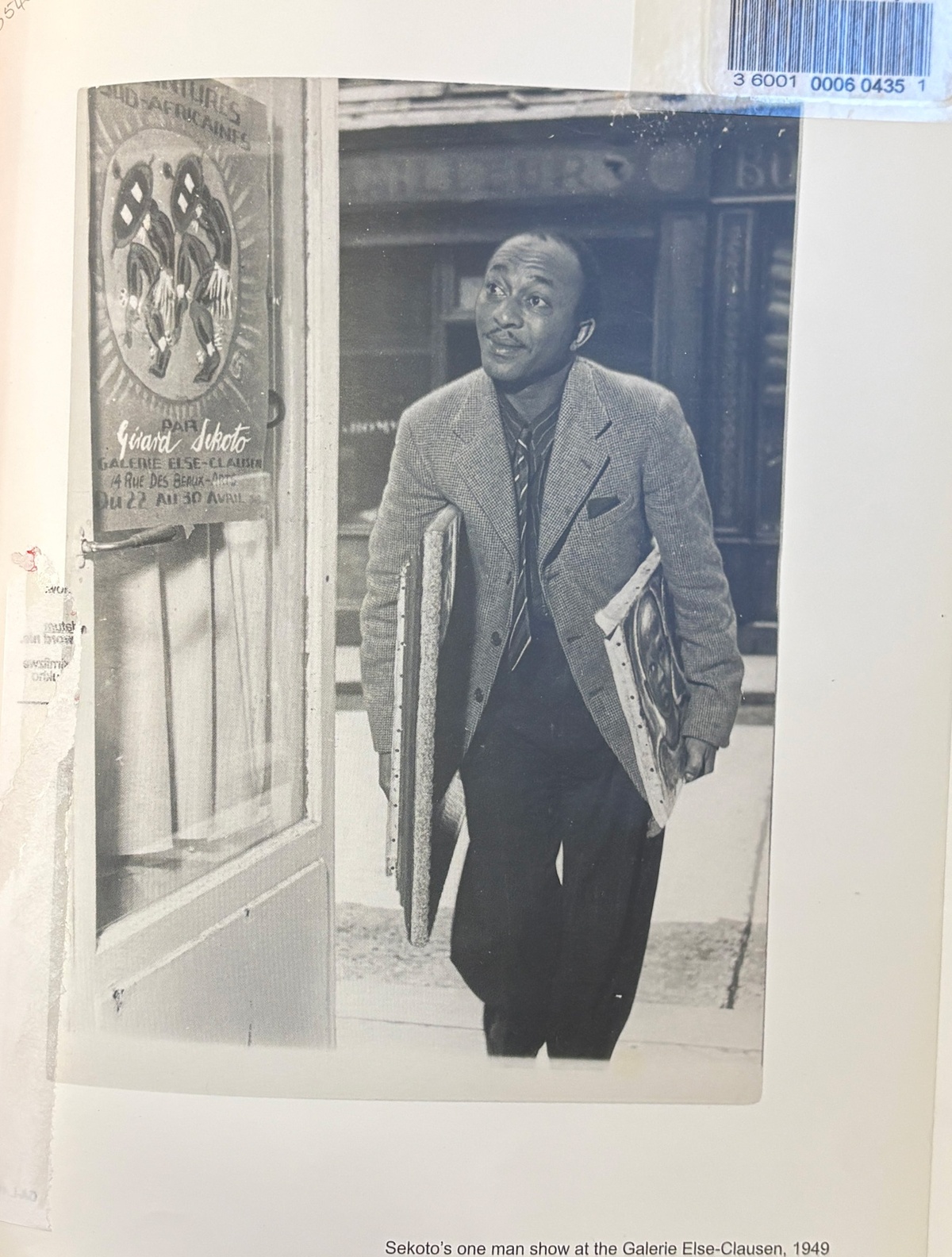

Aside from the skilled use of colour and form in Sekoto’s portrait of his mother Anna, the work’s frame exudes historical ‘aura’. Searching through books, we found that this frame is original, as seen (in better condition) behind Sekoto in a promotional portrait taken before he left South Africa.

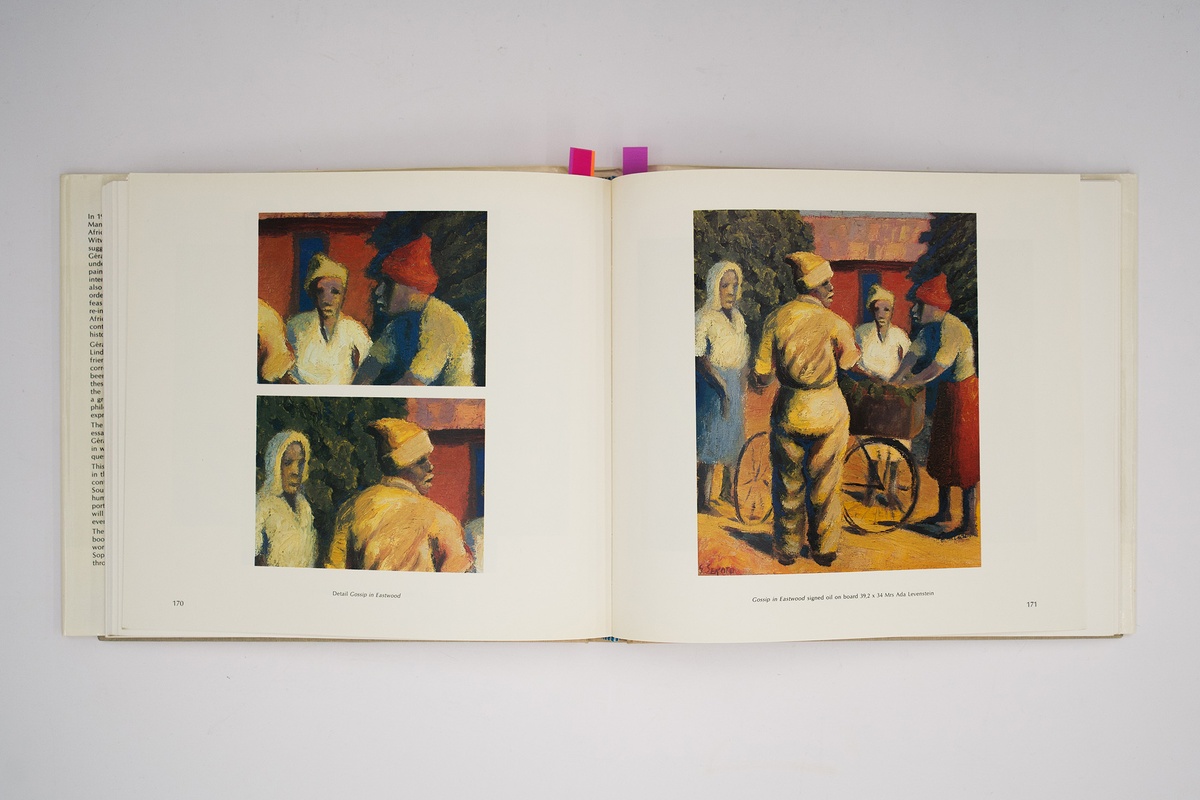

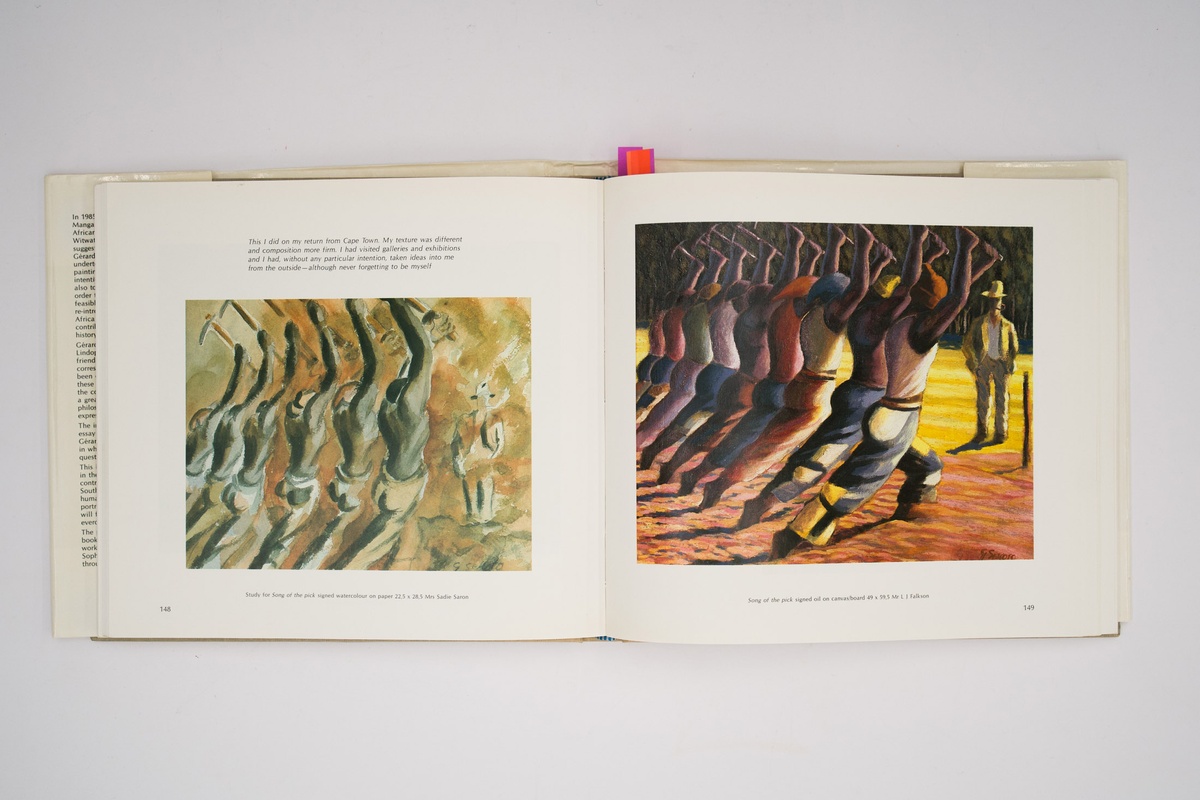

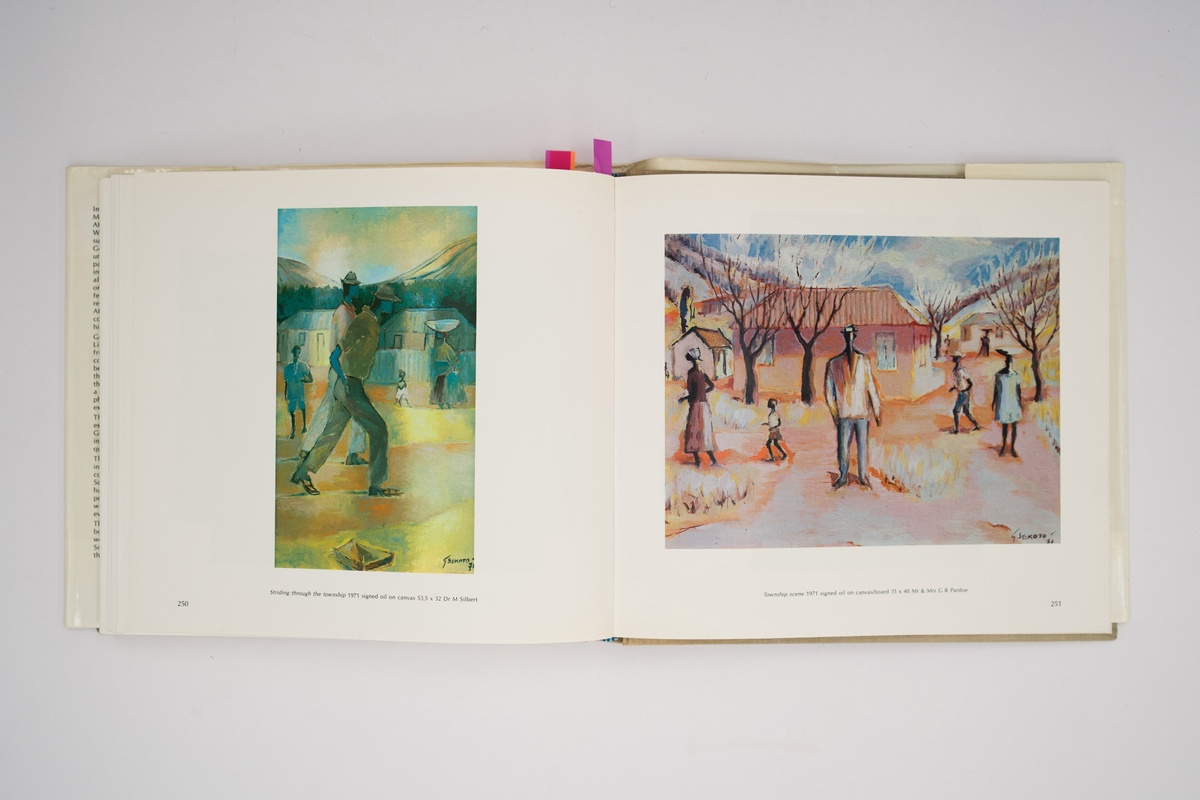

He moved to work in Sophiatown, Johannesburg in 1938 and then District Six, Cape Town in 1942, but reunited with his family in 1945 and lived with them in the Eastwood township outside of Pretoria.Curator Barbara Lindop describes this time in Eastwood as Sekoto’s ‘golden years’. He would continue to paint from his memories of this period long after he went into exile in 1947.

Was it possible for South African artists in exile to reconcile their practices with a new place? Inga Somdyala asked during his residency in A4’s Library.

You have never known what it is to be humiliated deep into the very mind as an individual as well as being a member of those people who are globally undergoing that same humiliation through the guilt in the colour of their skin. Therefore deemed as the oppressed.I left my land of birth on my own means and will. There where I pride my roots and where my mother first brought me to land upon the perplexities of life. Where I have become a citizen in a country where the law does not permit me the full citizenship.2

– Gerard Sekoto

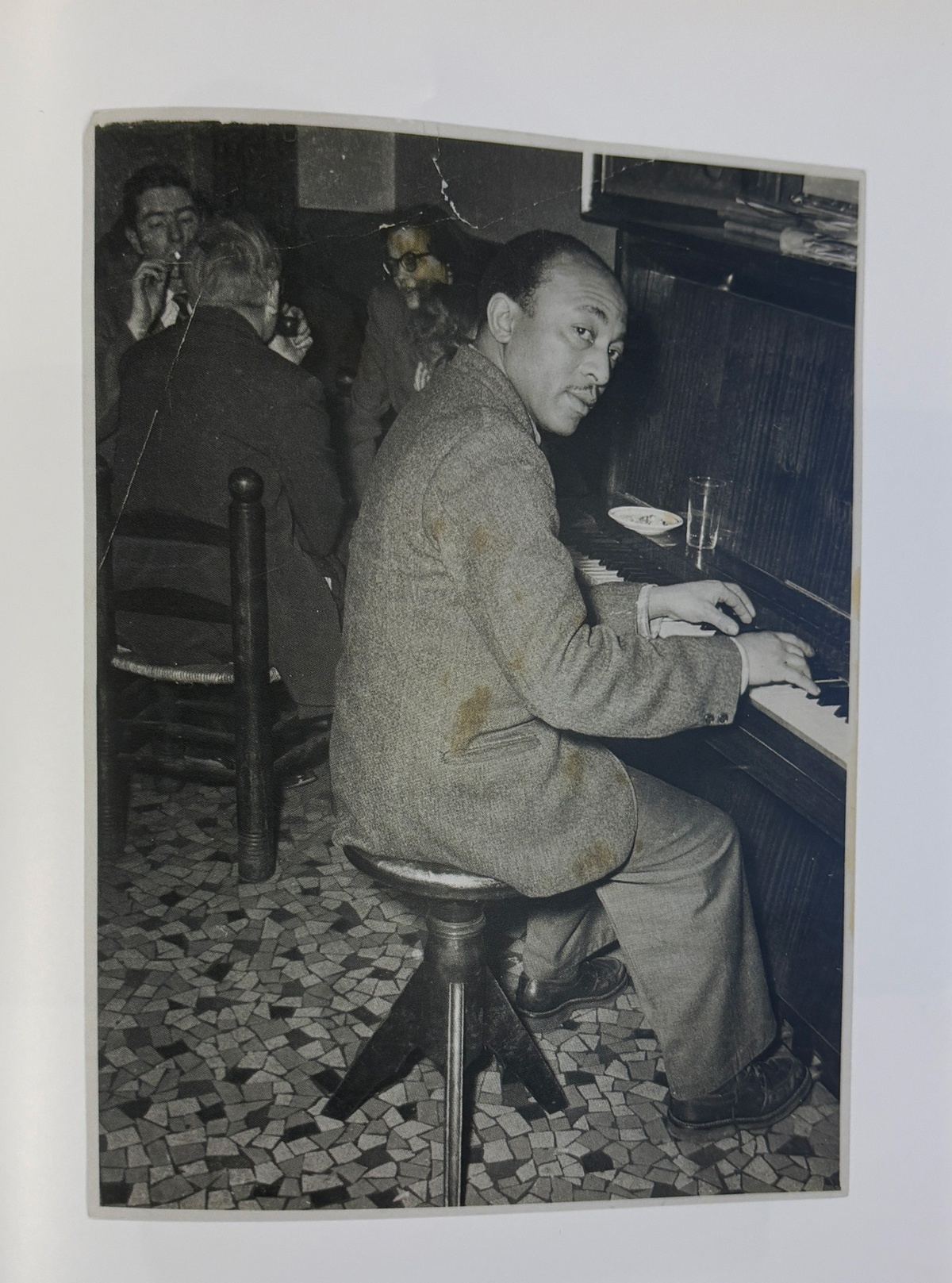

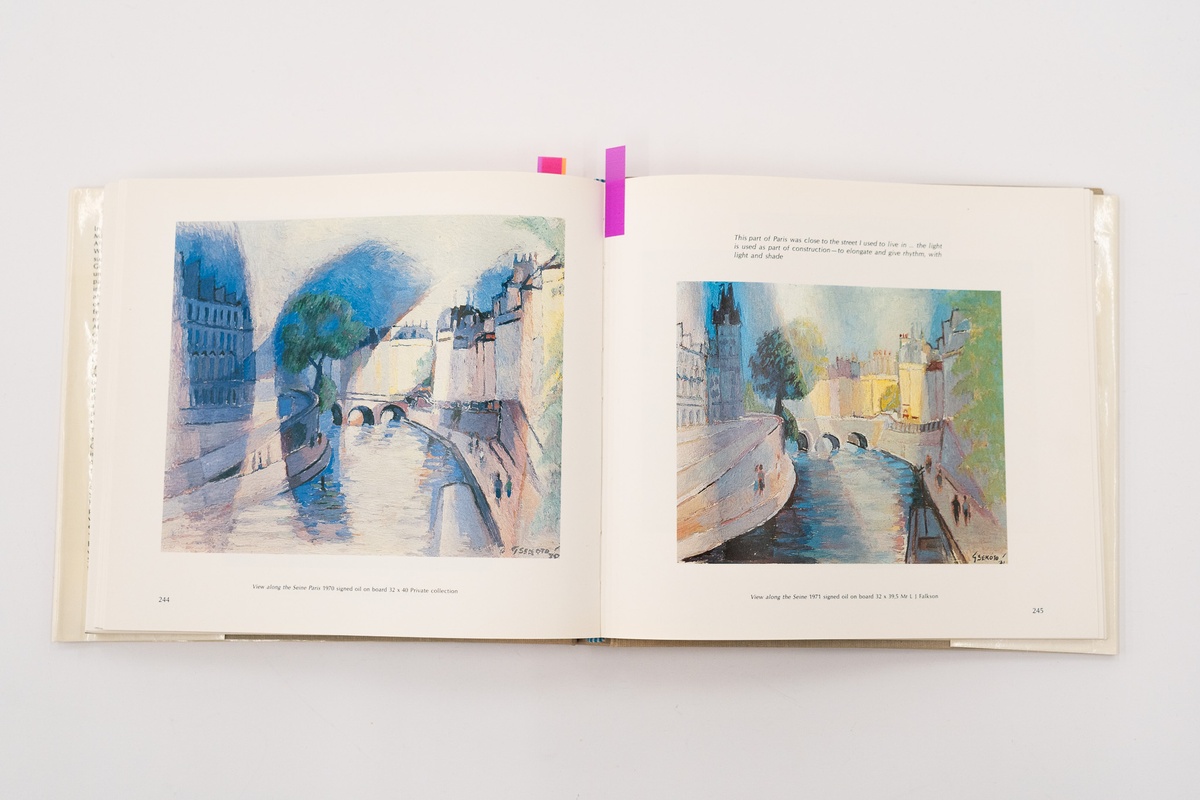

My subject matter was still of South African life as I had decided to hang onto it so as not to lose roots. I had made my little sketches in the Parisian streets and bars to put aside for later when I had gathered myself into the atmosphere as I would feel it.3

– Gerard Sekoto

Sekoto was both keen observer and active participant of Parisian cultural and social life. He exhibited new work and engaged with the cultural discourses of the day.He was also a musician, singing and playing the piano in jazz bars as an additional source of income.

It was difficult and still is to remain oneself in the enormous jungle of various characters all gathered together in this world wide reputed city of arts.4

– Gerard Sekoto

The tragic irony of Sekoto’s exile is that having realised his dream of being able to leave South Africa, he was forced to pay a high personal price. His art, which had drawn such poignant inspiration from the environment which he knew so well, slowly lost its strength and character.[...] In exile he continued to recreate South African subject matter but he failed to identify himself with his work. It was as if he felt obliged to paint what the public expected of him as a black South African artist.5

– Barbara Lindop

Barbara Lindop’s assessment of Sekoto’s work as ‘losing its strength’ in exile is based on years of conversations with the artist and close readings of his work. It expresses an expectation that he reconcile himself with the ‘in-betweenness’ of his circumstances – never fully French but also not treated as being fully South African by the apartheid state. Perhaps this expectation was impossible to meet.

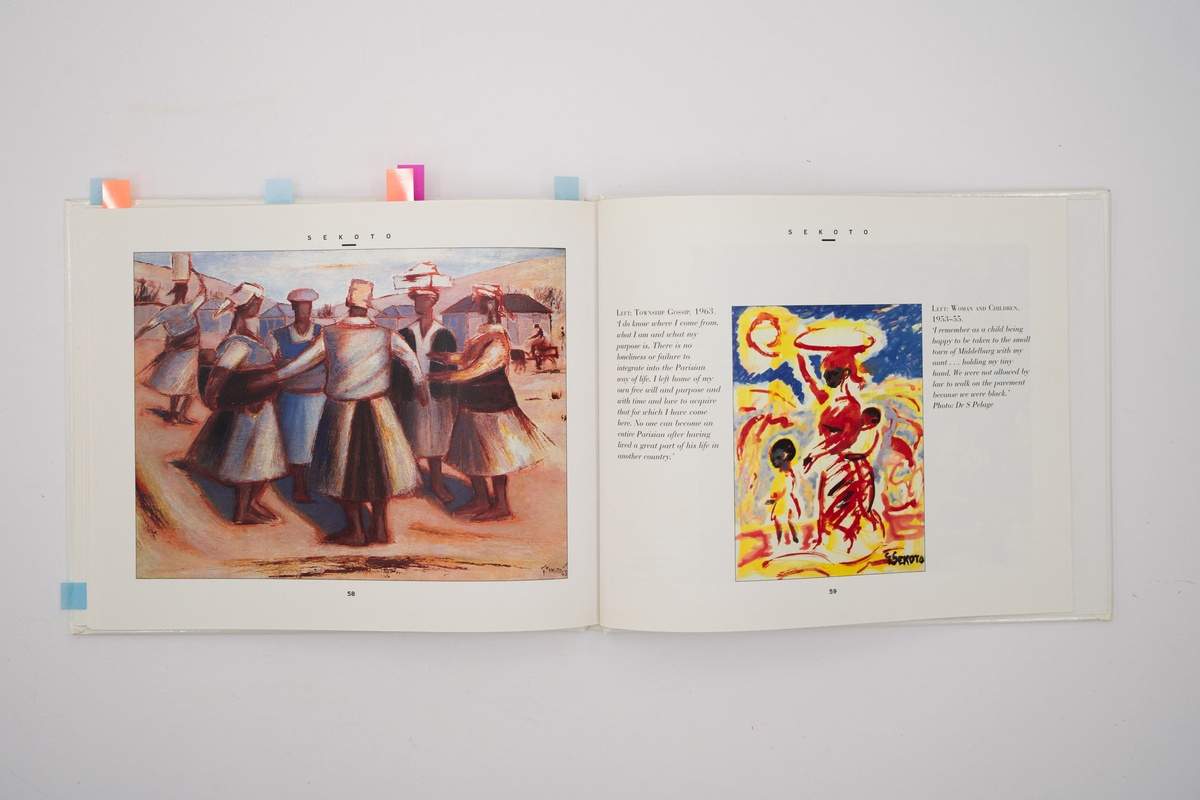

I do know where I came from, what I am and what my purpose is. There is no loneliness or failure to integrate into the Parisian way of life. I left home of my own free will and purpose and with time and love to acquire that for which I have come here. No one can become an entire Parisian after having lived a great part of his life in another country.6

– Gerard Sekoto

Sekoto asserted his agency but has also acknowledged the difficulty of remaining rooted in an increasingly diffuse conception of what and where home is.Though these tensions are placed in relief by the extremity of exile, experiences of unbelonging are central to artistic practice and the human condition.By painting his memories of Eastwood township, coloured by the palette of winter in Paris and with the sinuous, sophisticated figures he found in Dakar, Senegal, perhaps he was constructing a new home for himself unlike the place he had left.

Footnotes

- Lindop, B., and De Beer, M (eds.) (1988) Gerard Sekoto. Johannesburg: Dictum, pp.116–117. Available here.

- Lindop, B. (1995) Sekoto: The Art of Gerard Sekoto. London: Pavilion Books, p.17. Available here.

- Ibid. p.19.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. pp.17–18.

- Ibid. p.59.