Ernest Mancoba at Home

Inga Somdyala

Reflections on belonging in dialogue with Bridget Thompson’s documentary film Ernest Mancoba at Home (1994), which follows the artist's brief return to South Africa in 1994 after almost six decades' absence. – October 1, 2025

Ernest Mancoba has never felt so vivid to me as he does in film. The moving image collapses all my separate points of reference into something textured; history feels nearer, tactile.

Before having seen Ernest Mancoba at Home, the photograph of the artist I would return to most readily was a 1994 portrait of him in a light-coloured blazer, scarf, and black beret, backgrounded by an oak tree in Cape Town’s Company’s Garden. The clear winter sun is dappled by oak leaves, landing softly on his bust.

I look at it and think: having struggled to establish himself as a human being – and an artist – in the years prior to the formal institution of apartheid, how does the sudden political “happy ending” of a newly democratic South Africa affect his experience of returning to his native country as a French citizen? I wonder if his eyes reveal relief, or betray discomfort.

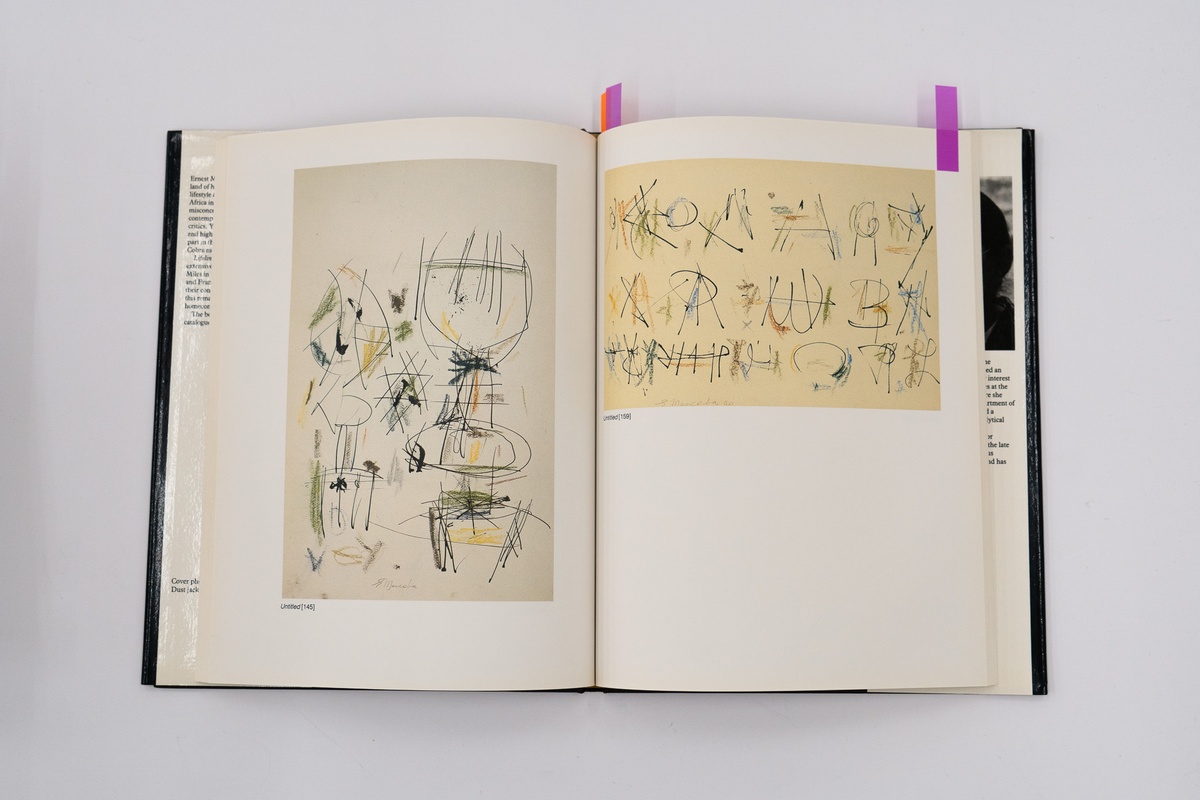

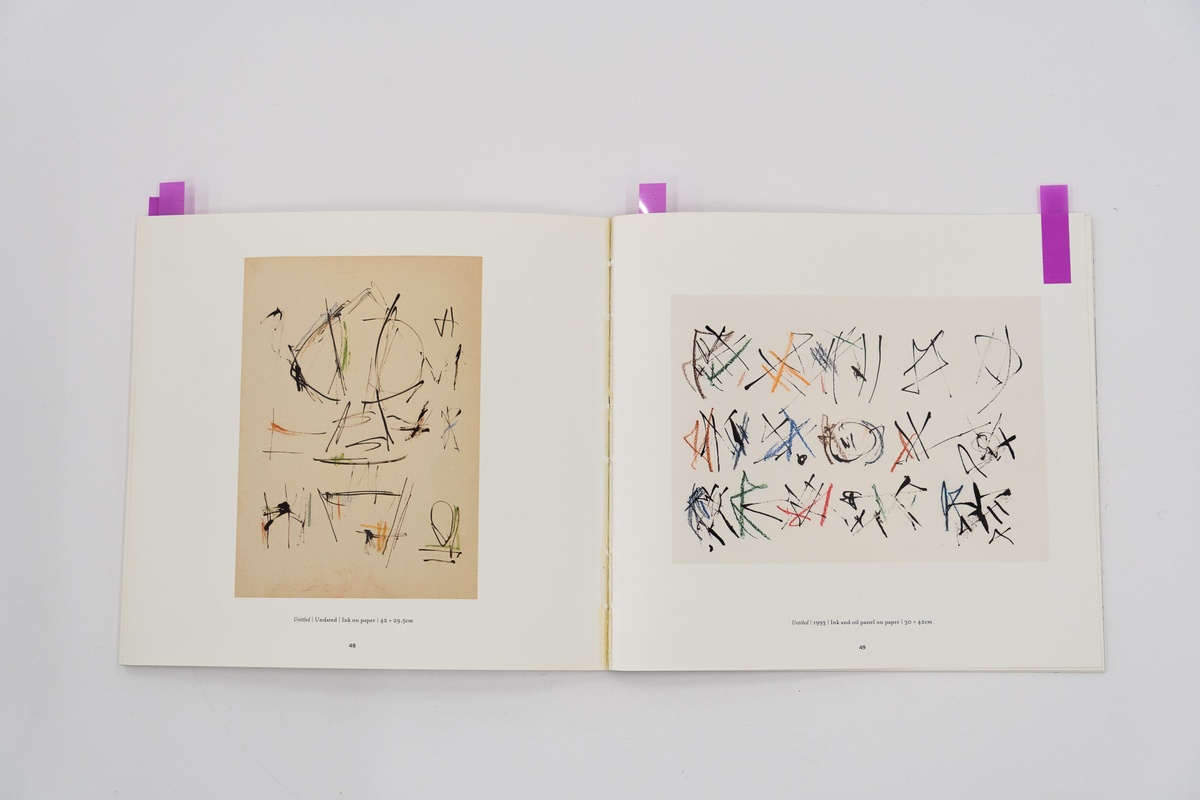

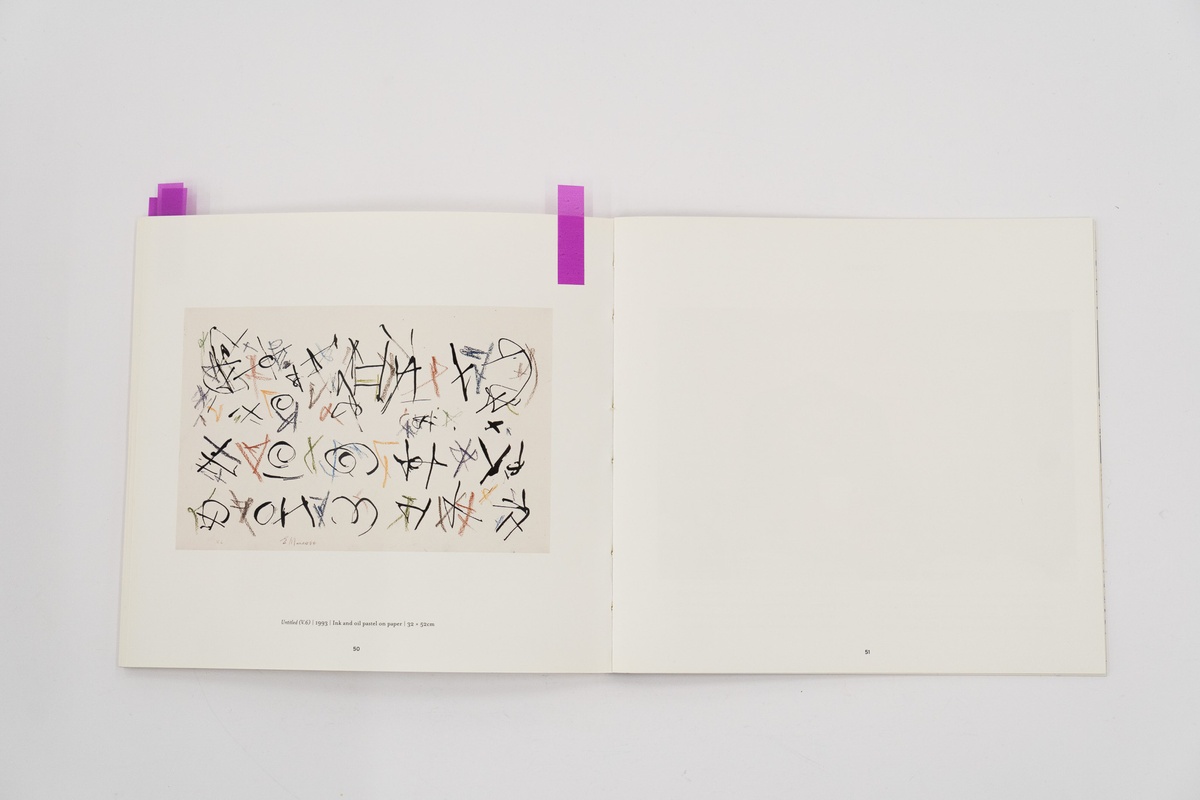

In the film, Mancoba’s expression is distant when he searches for a phrase that approximates this “unspeakable” experience, expressed in the work. The decisive pauses in Mancoba's speech recall a fundamental painting approach he later described as marks made with the “lightest means possible”. That is, an approach reduced to essential gestures landing sparsely on the surface.

Making quick, successive marks on a blank canvas, Mancoba speaks about drawing his palette from the colours of the rainbow. When he says this, I think about Mancoba’s lifetime in parallel with the genealogy of South Africa’s flag – from 1904 through to this Rainbow Nation moment in 1994.

I’m especially drawn to this transitional moment in South Africa’s history, which is distilled in Mancoba's being honoured in a public institution just months after the first democratic elections, when Jane Gool Tabata delivers an elliptical umntu ngumntu ngabantu from Mancoba’s acceptance speech. The university hall erupts in applause. I understand this as a moment of full-blown Rainbow Nation euphoria.

I later recall James Baldwin’s remark: “In the heart of that confusion he encounters here is that which he came so blindly seeking: the terms on which he is related to his country, and to the world.” 'Here' is generally exile, but for Baldwin too, specifically, it was Paris. I wonder if one ever fully reconciles with home after making home all over again in exile.

I’m curious about that complicated relationship with belonging – in exile, in return. I see something generative in thinking about Mancoba’s return 'home' to South Africa as a French citizen.

There’s more to be said on exiled artists, their work, and their own words – some of which I’ve been exploring. I write as I dig, trying to bring those histories into the present, to speak through them and alongside them, to talk about my own experiences and work.

I’m driven by a sense of a distant cultural heritage that must be claimed, reckoned with, worked through, made present, placed on the lip.

Mancoba’s work feels urgent to me now. He was searching for ancestry, and I share that curiosity about origins. In the film, he also mentions his “dual-faith” upbringing – Christian and traditional Nguni spiritual practices coexisting. This is the “threshing floor of faith” that Santu Mofokeng also wrote about, and which speaks to my own experience.

I am inspired by the film to further explore ways of talking about this experience as something shared but deeply personal, and historically relevant to contemporary black life.