James Webb

Prayer is Webb’s most ambitious and expansive installation. Begun in 2000 in Cape Town, The Future Is Behind Us offered all the recordings – as many faith groups as Webb could find within the ten cities he has included over 22 years of Prayer. With the prayers of each city sounding asynchronously, the moment the visitor stepped onto the carpet was unlikely to be repeated; the work offering almost infinite combinations.

–

The following is an excerpt from a conversation between James Webb (J.W.), Josh Ginsburg (J.G.), and Sara de Beer (S.D.B.) in preparation for the Future Is Behind Us, 5 December, 2022.

S.D.B In our previous exhibition, Customs, Sumayya Vally referenced a conversation she had had with you, James, in which you spoke about the work, Prayer, as being like a sun. “Can a project be like a sun?” Sumayya asked. She continued: “I think so. The process of Customs has been like a sun for me.”

J.W. The artwork Prayer can be thought of like a sun, because new artworks came out of it, as well as new friendships. Prayer has created connections and given life to other projects.

J.G. This exhibition, The Future Is Behind Us, is an opportunity to walk backwards into nowhere. You pass things that come into view. You may choose to collect them in your sight; see what comes from them being in relation to one another.

The challenge is to not reach too far forward into what it is, or what it could be. Let it play itself out.

J.W. There are ideas and flows of time happening in the installation: the work is a space where all these time-based events have taken place.

I made the first Prayer in 2000, in the so-called (and in inverted commas) ‘post-Apartheid’ city of Cape Town. Religion has always played a part in South Africa, both in Apartheid, as well as in anti-Apartheid movements. I wondered: what would it be like to hear so many different people praying at the same time? I wanted the group; the many – the merging of different positions and beliefs.

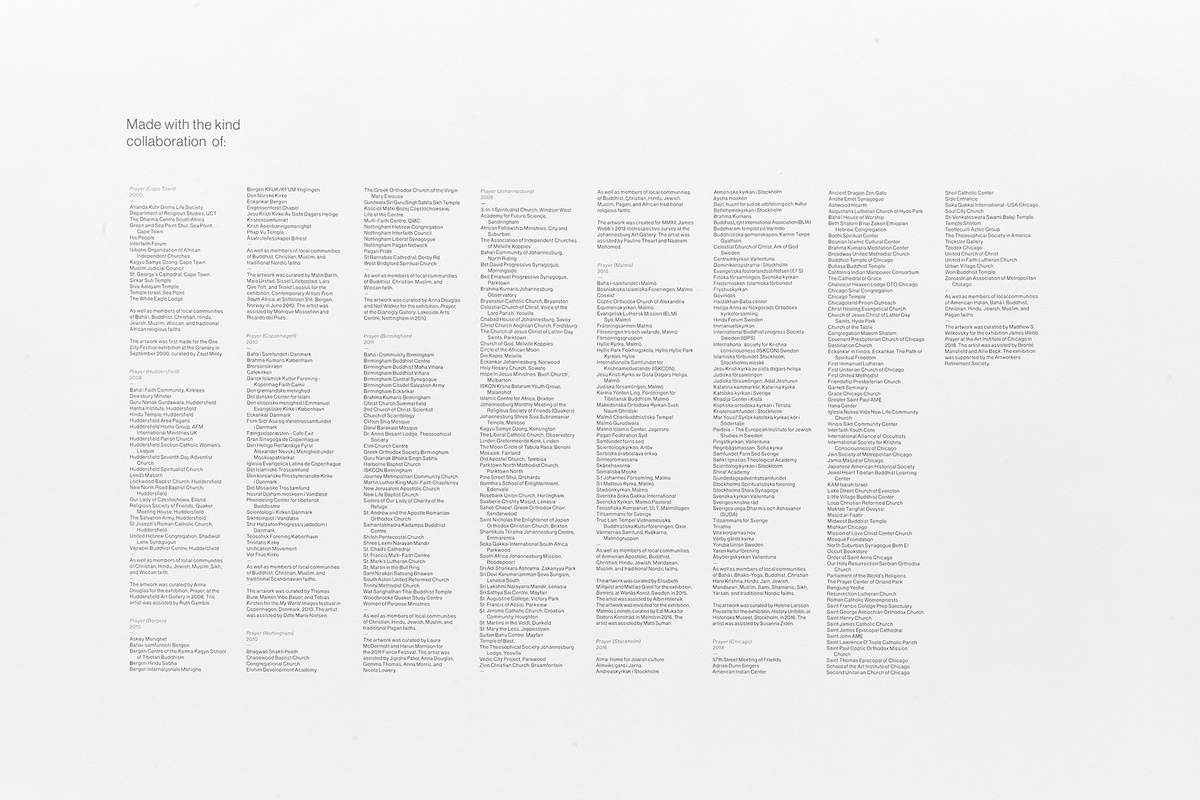

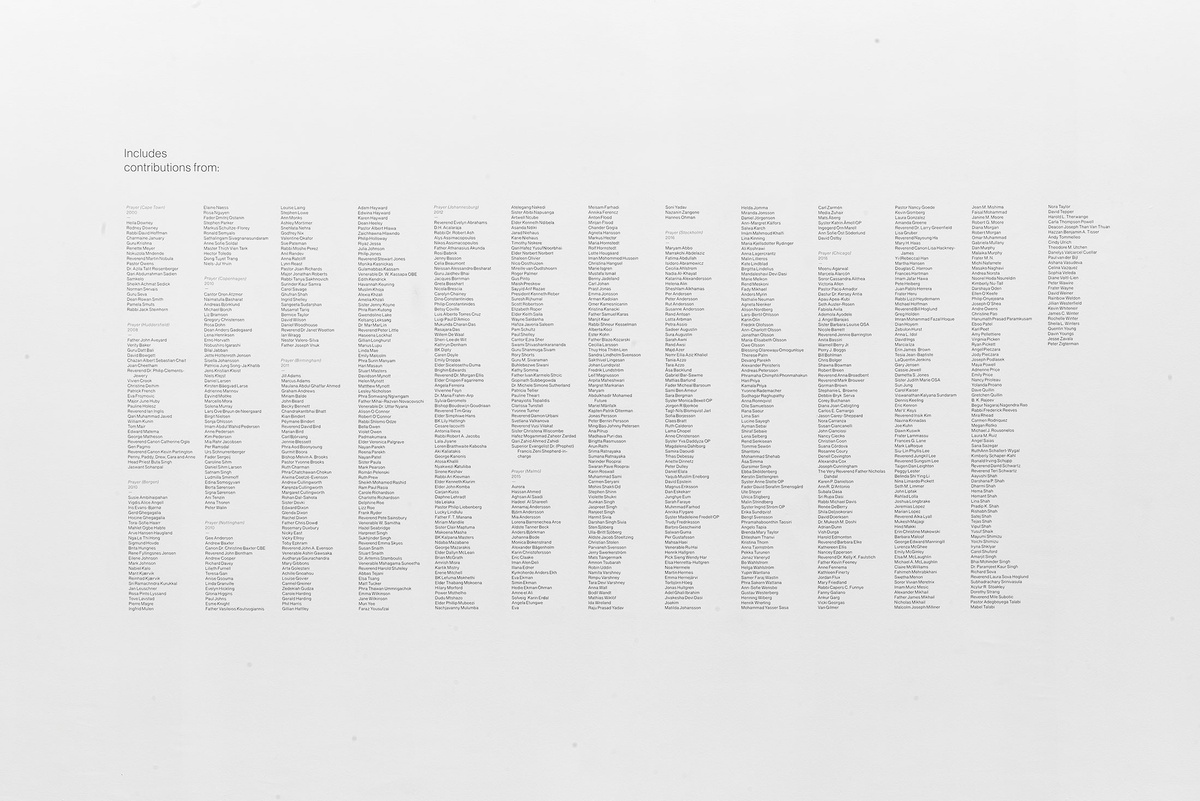

Prayer has since taken place in ten cities, over the span of 22 years. Each version of Prayer is of its moment. It’s not a municipal census. I ask people to help me, and those that will, do. I couldn’t make the work without them. Prayer creates kinship and community. My interest in this has created a problem I have to try and solve with the help of other people.

J.G. What would you call it now if you could rename it?

J.W. Prayer is an umbrella term: it’s where I was in 2000. Would I call it Untitled now, I don’t know. Each time it is created it’s new because the world has changed. There is Prayer before, and then after, 9/11. Before and after the invasion of Iraq. Before and after Jacob Zuma. Within the prayers are recorded historical moments: in Prayer (Malmö), for instance, a Vietnamese Buddhist priest prays for the ships carrying refugees across the Mediterranean Sea. Another participant prays in the morning, upon waking, “Thank you, God, for letting me wake up sober this morning.” Gordon Brown is in there insomuch that he was prayed for by some of the participants in Prayer (Nottingham) in 2009. There are prayers that reach beyond the lines of everyone’s assumptions. Religion is a political force, and it is also social care and self-orientation.

J.G. Is it a cacophony? Is it a Babel moment? A collapse or an arise?

J.W. It’s many things, and, in a way, those descriptions are up to the audience. When you enter the gallery you see an event and you hear an event. A thundercloud, a garden, a mass, a symphony, a gurgling: someone once said it’s the sound of God’s answering machine.

Then there is a choreographic moment; a change as you take off your shoes and feel the carpet under your feet. Step within the voices and you are now part of a community. When, as an artist, I enter a place of worship, I am entering into a new space as a guest.

You can tune in and out, intercept the shimmer of voices around you, or you can kneel down, genuflect and hear just one. But that one isn’t taken out of the context of the many.

J.G. How did the project change your lens of each city?

J.W.: I can say what I found: I found hospitality and humanity. I have been moved by the positive responses, by the hospitality of people willing to share their time and their beliefs and practices with me. There are people who disagree with one another but who are happy to be recorded together and to be listened to.

Listening, which is a lot of what Prayer is about, changes one’s perception of the world by giving time to the world. I am interested in listening because it requires one to give time and respect and an openness to the person and/or environment you are listening to – there's a pausing of other activities and a focusing of attention. Adam Phillips speaks of therapy as the ‘listening cure': we find something when we listen to ourselves and know someone else is listening to us.

J.G. The work tinkers with infinite combinations. The prayers play asynchronously, and this is the first time that all the prayers have been heard together, in one place. Each person’s moment on the carpet will be a different moment.

J.W. I like to think that visitors to the piece are remixing it as they move from place to place along the carpet. Perhaps their perspectives of the city are expanding, mixing, and remixing then too.

J.G. What is your geometry of time?

J.W. I think of these 10 editions as time capsules. To pray locates one in the moment, honours the past, and perhaps, is desirous of some kind of future. Absence is a key thing in my practice; the imagination goes into that absence and attempts to populate it. Prayer, the artwork, is a request that is answered. This is a lifelong project. At least, I hope it is.

b.1975, Kimberley

There is in James Webb's work a gestural eloquence in form and thought, a distillation of idea akin to haiku. While his primary medium is sound, the artist suggests that “listening and doing nothing” perhaps better describes his preoccupations. “Listening,” Webb says, “is a very hard thing to do. It’s about paying attention, and being open to the unknown.” Indeed, he is no stranger to the unknown, inviting such themes as the occult and spiritualism into his work. Attuned to the poetics of the ordinary and understated, his work draws attention to the numinous in the normal. With objects minimal and more often monochrome, Webb lends to his sounds a material housing. Some he allows to exist as only aural offerings – birds calling from trees, voices singing under bridges. Few remain silent yet are all the more compelling for their quiet. An unseen stranger coughs in the gallery, a voice directs a series of questions to five litres of Nigerian crude oil – “What do you remember of prehistoric sunlight?” – a microphone records its journey to the bottom of a mine shaft, a broken clock becomes obscure religious symbol.