George Hallett

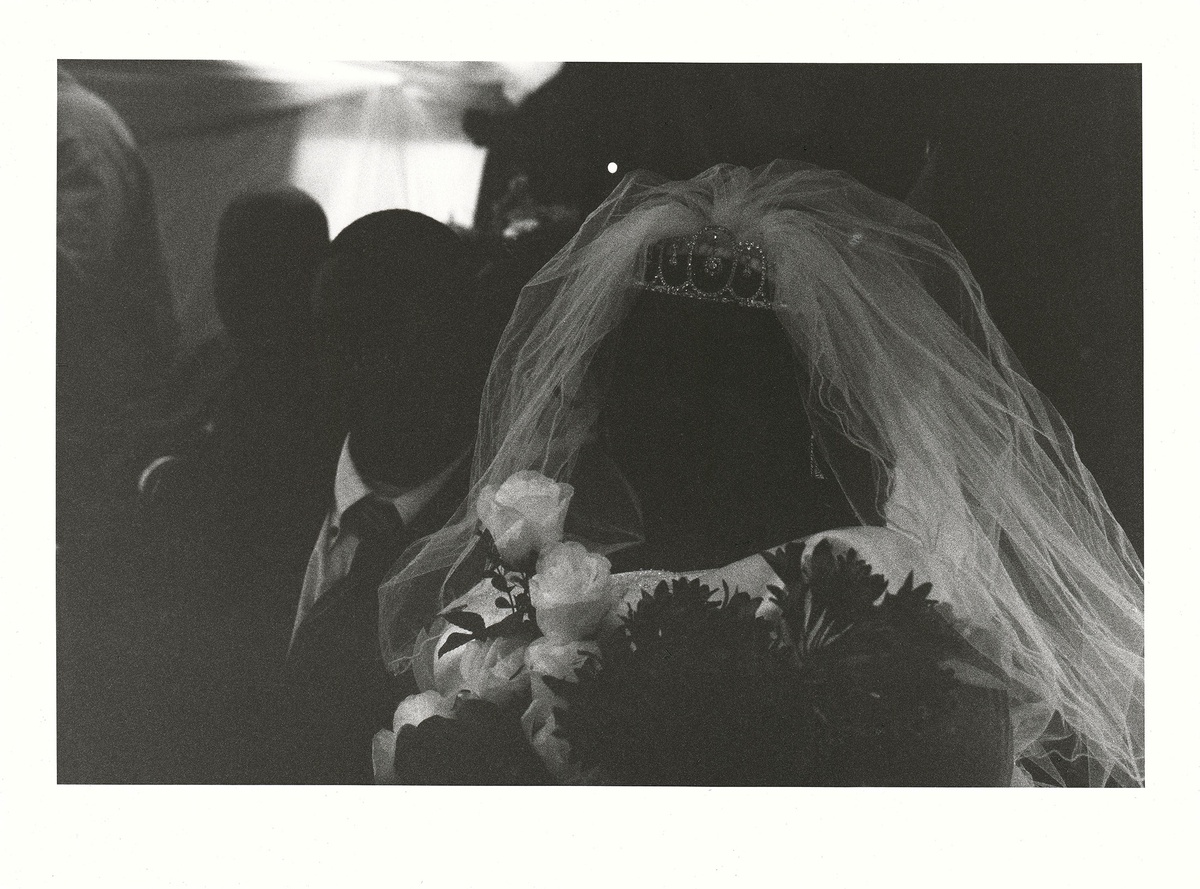

Peter Clarke’s Tongue is a tribute to the coupling of old friends. Photographed in France, it comprises two parts. The first is an intimate portrait of artist Peter Clarke cradling a cowbell, his eyes downturned. The second image is a subtle study in foliage. The diptych’s title offers more questions than answers. It is startlingly intimate; sensual and sonic. Can Peter Clarke’s tongue be found in the bell’s clapper? In the whispers of wind finding grass? In a story Peter told George that day? Of his time in France, Hallett said:

I started photographing more abstract stuff – patterns, textures. I took portraits of Peter Clarke there – an amazing portrait, the one with a cowbell. James Matthews in the water. That’s there. They came to visit me there. We played with each other. I photographed Peter in a Basotho hat, I photographed him stripped to the waist, doing all kinds of things. It was great.

Clarke continued living in South Africa (in Ocean View, where he was moved by force when his home of Simonstown was declared a ‘whites-only‘ area under the apartheid government’s Group Areas Act), when many artists of his generation went into exile. The comfortable silence located in the space between photographer and subject is testament to the enduring tenderness between two friends.

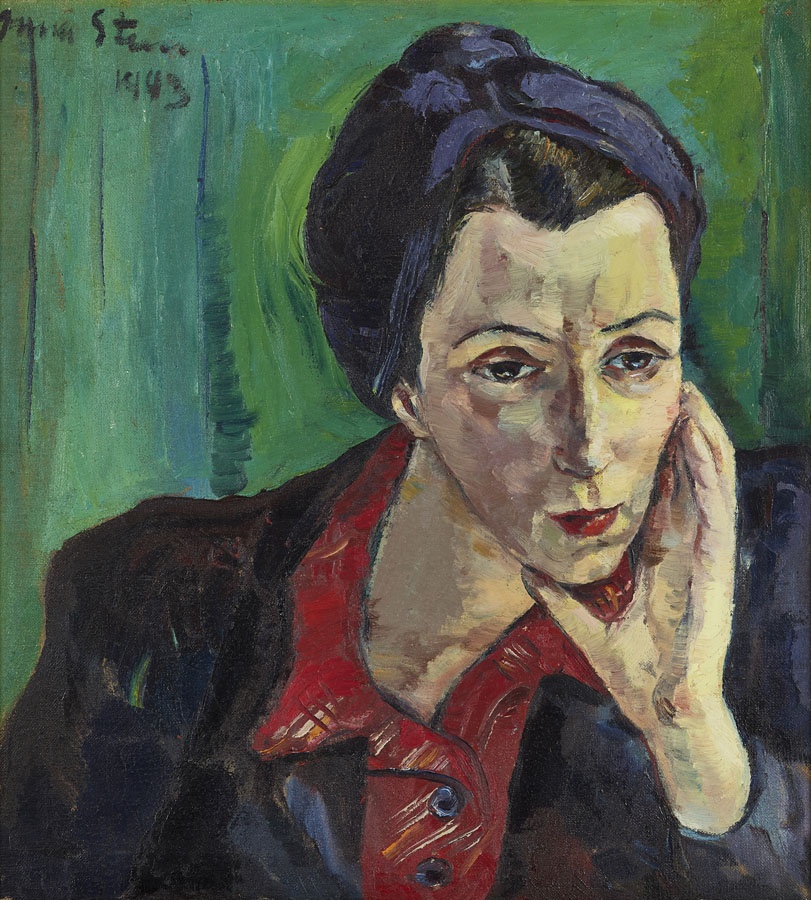

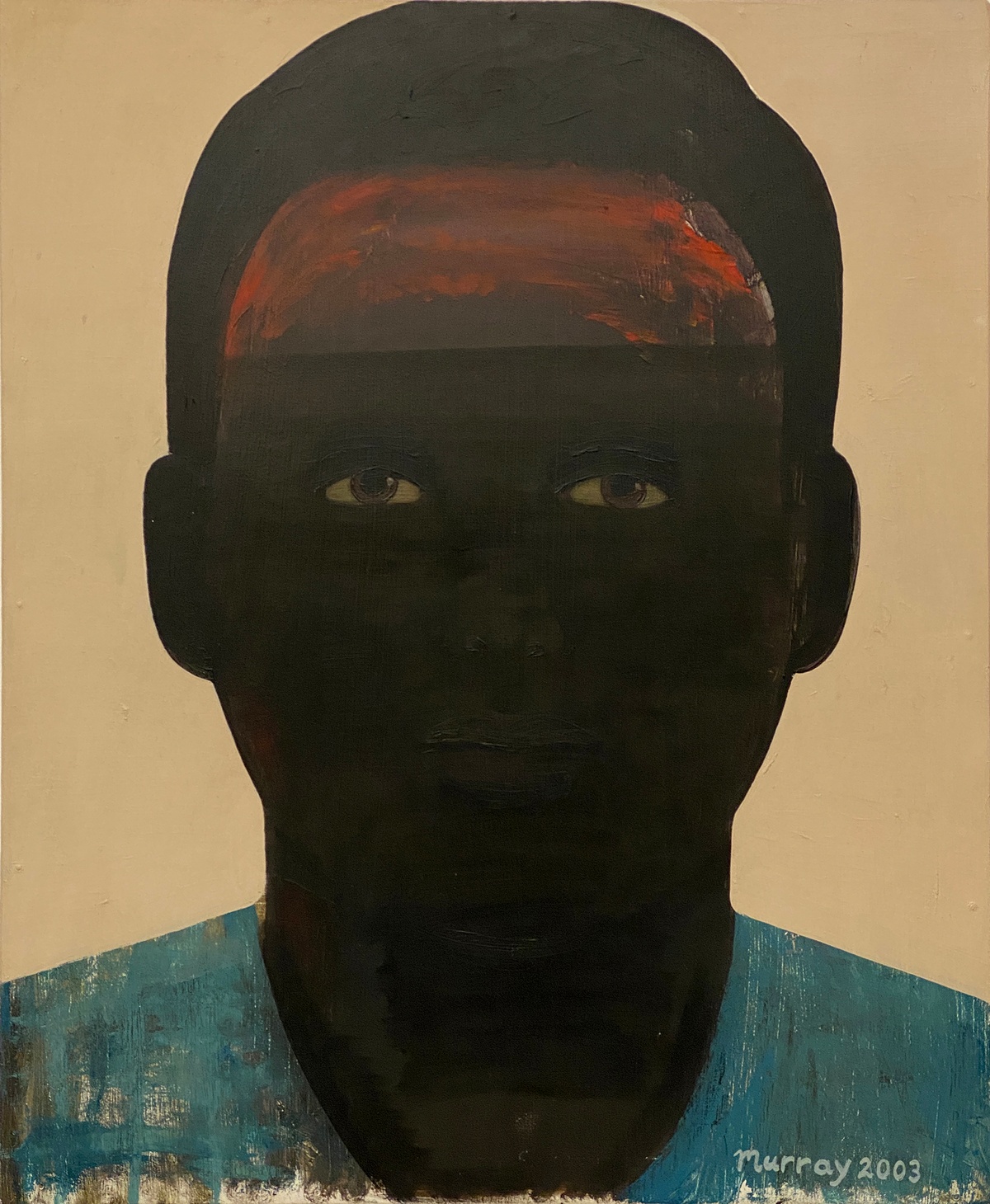

Editor’s note: Clarke’s painting Anxiety (1969) was included in the exhibition Customs at A4, visible in the distance behind this portrait by his friend.

b.1942, Cape Town; d.2020, Cape Town

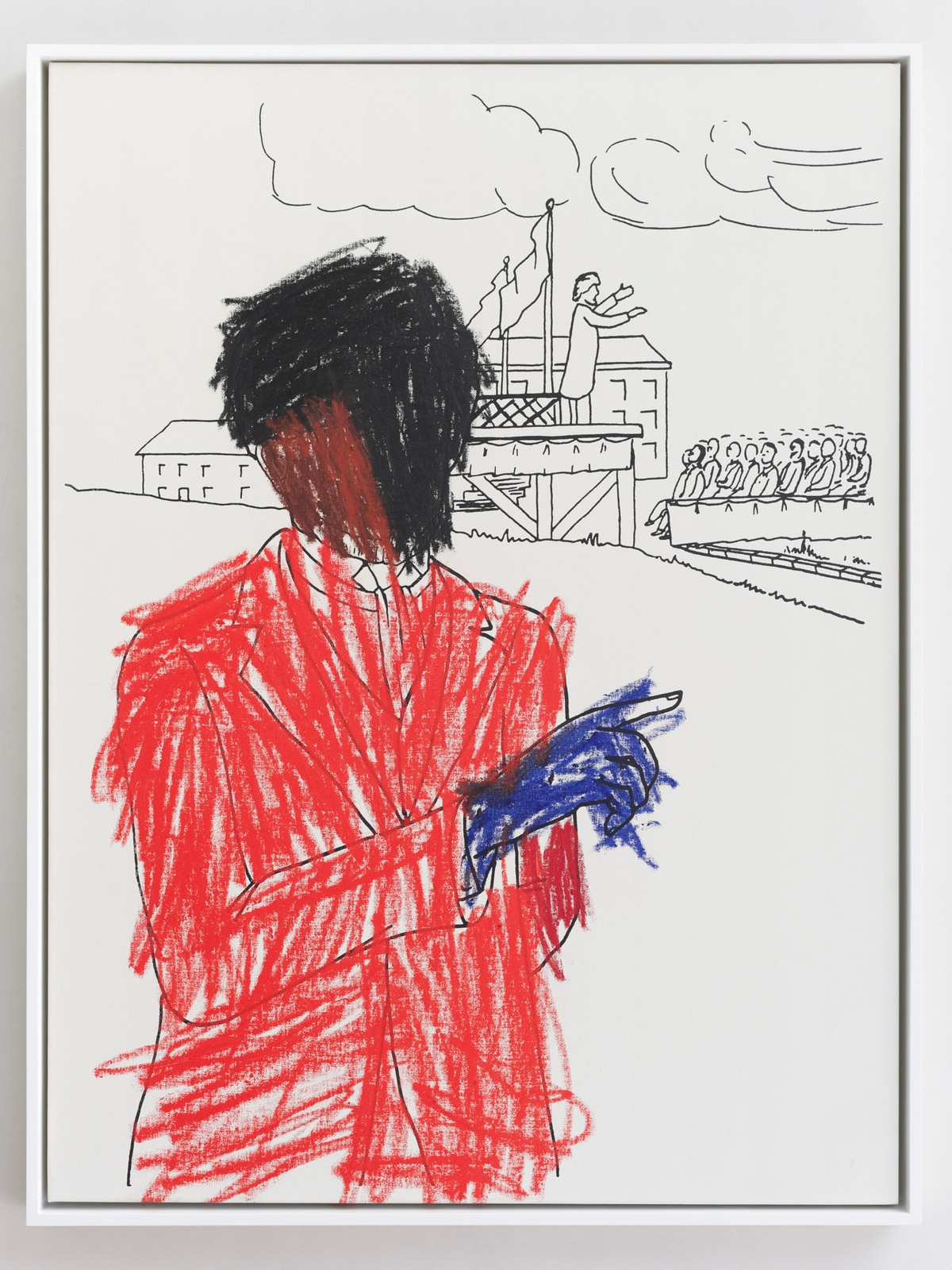

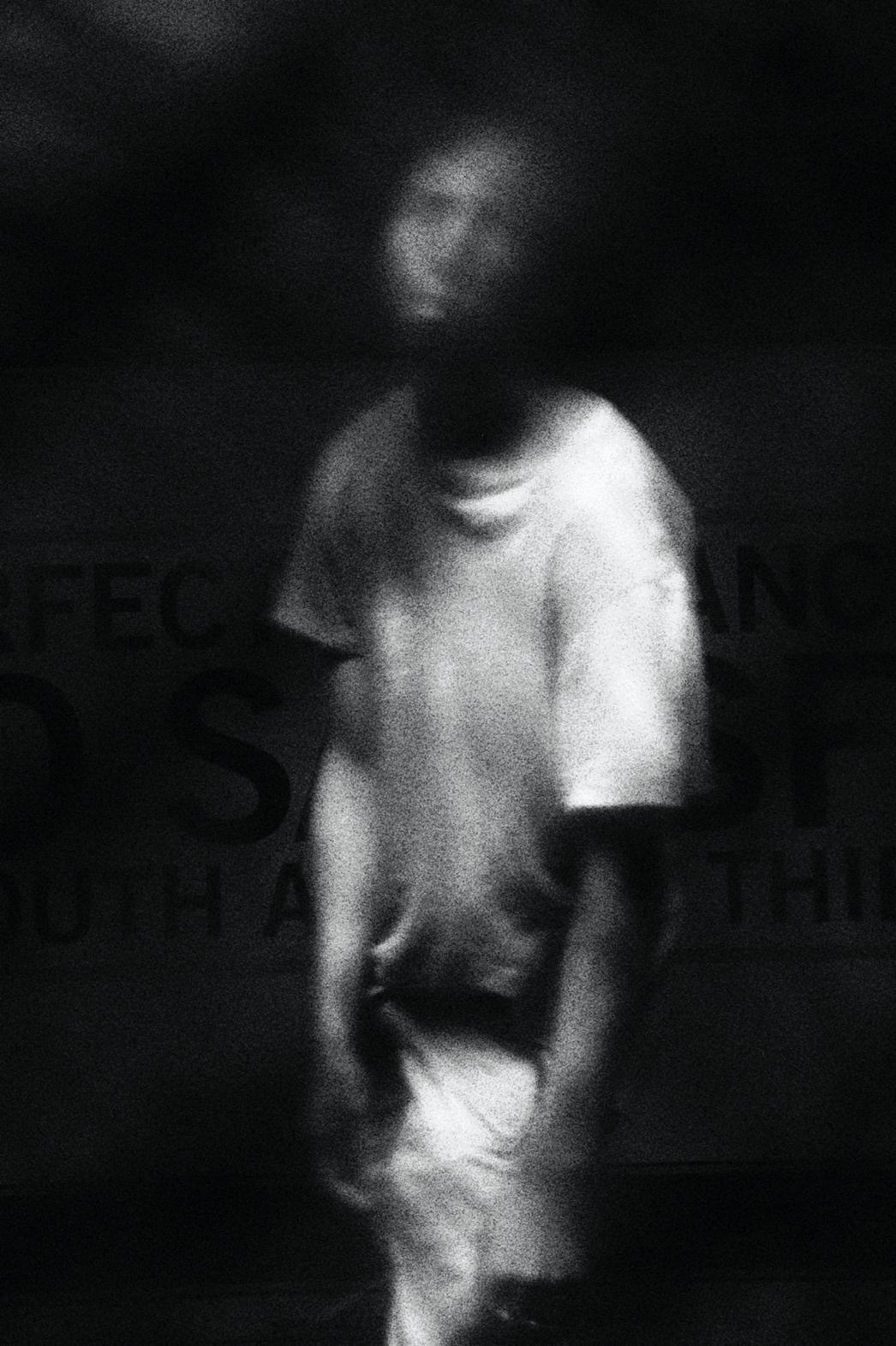

George Hallett’s photographs traverse geographical borders and political regimes. Hallett, who first gained recognition for his photographs of District Six, moved to London in 1970 to escape the untenable racism and violence of apartheid South Africa. He established collective homes away from home with other South African exiles in England and France. His images of these writers, artists, intellectuals, and activists embody intimacy. Hallett’s humanist approach to photography intercepts the camera as it seeks to separate himself, the silent observer, from his subject. In his words: “I became the camera...aware that when the lighting changed, [then too] the mood changed, the music changed.” Returning in 1994 to document South Africa’s first democratic election for the African National Congress, his photographs possess an optimism that distinguishes them from those of his contemporaries. This optimism does not compromise the integrity with which Hallett captured sombre scenes; instead, it points to historical texture, to dispersed beauty, and to the fervent complexity of a transitioning South Africa.