Yoko Ono

Through Sky T.V. in 1966, the eternal sky was invited indoors by way of a 24-hour live video feed. Yoko Ono subverted the anxiety that would come to surround television, made manifest in the material of the ‘TV dinner’ and its associated mindless consumption. Instead, the TV is an open window to the miraculous sky and all its promises – whether to be blue and clear, or disrupt the world with tempers. Ono imagined the work while living in a windowless apartment. The artist’s instructions read: “TV to see the sky: This is a TV just to see the sky. Different channels for different skies, high-up sky, low sky, etc.” Ono often collaborates with the sky in her work – as mirror, as escape; the sky as artist. Where the viewer is invited to witness the sky’s unbounded capacity to make out yonder, free of human interference, the sky, personified as conductor, performs like a god. Its metronome holds us in time, dictating our night and day, whereas, when a plane appears in the TV’s view, it’s but a blip, a mere actor stepping into frame for a small moment with little influence (like the way a van driving past the City Hall can’t drown out the orchestra’s symphony). Perhaps the germ of the sky’s intractability was conceived long before – the artist, as a child, remained on the outskirts of Tokyo throughout World War II. A sky flooded with hydrogen, alight with fire, would eventually climb out blue, defiantly redeeming its sunrise and set.

b.1933, Tokyo

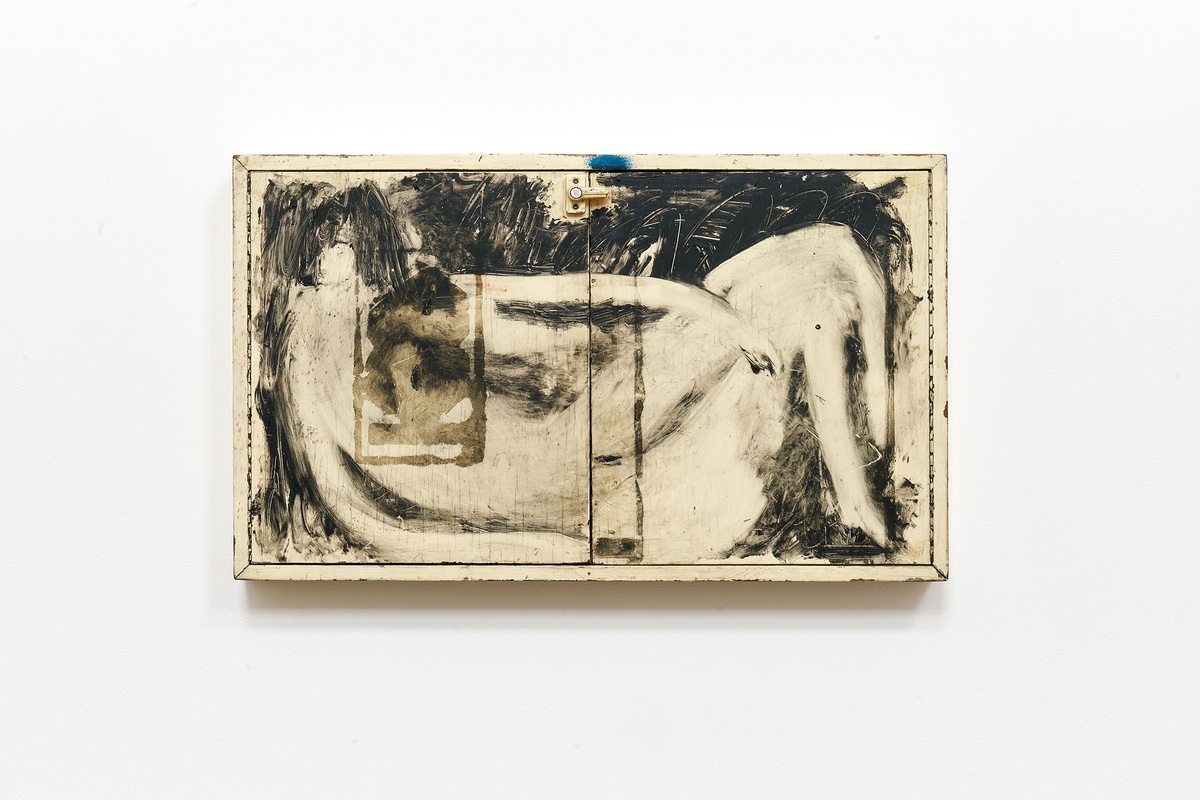

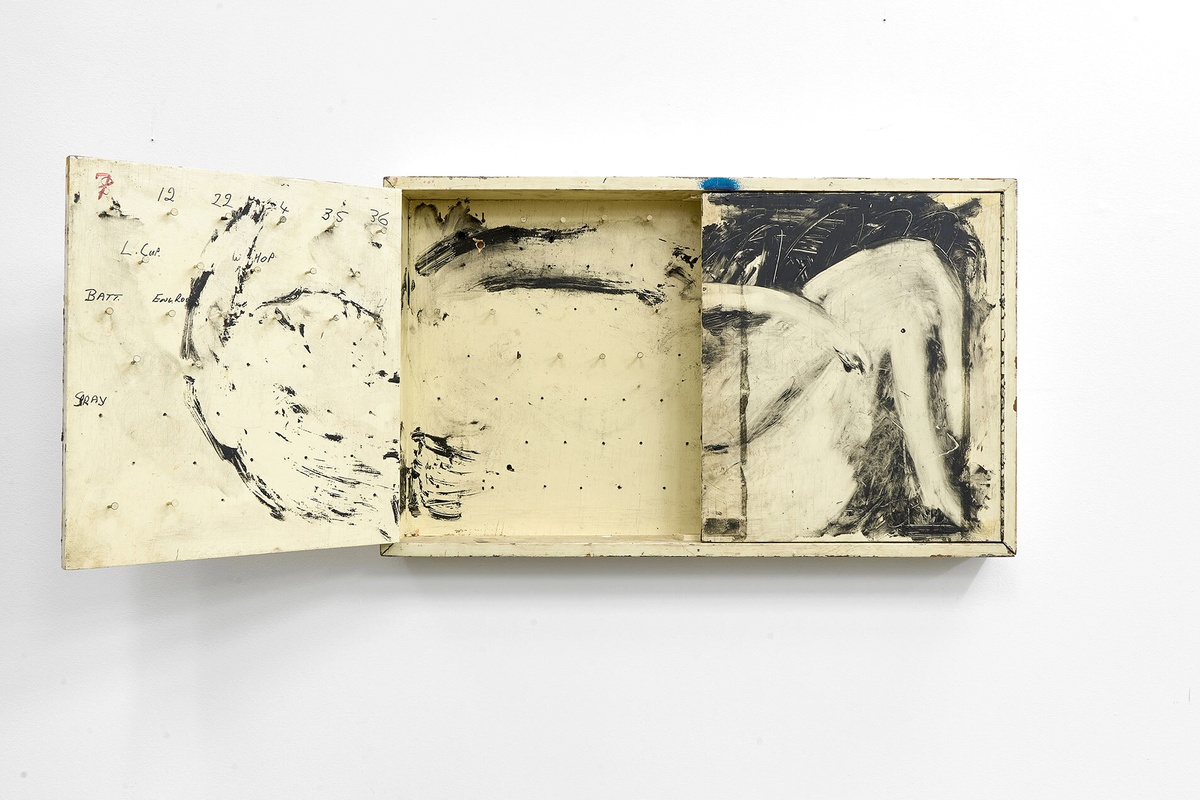

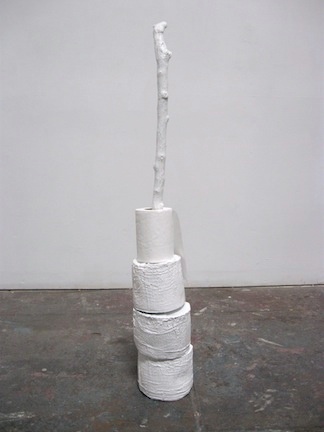

Among the art objects Yoko Ono has made, many have necessitated their own disappearance, much like Smoke Painting (1961), a canvas accompanied by the invitation to press lit cigarettes into its fibres until the fabric has all but burnt away. Drawn to the ephemeral, the incomplete and understated, those among her works that find no material expression persist instead as text, performance, film, or as koan-like instructions: “Light a match and watch till it goes out,” “draw a line until you disappear,” “make one tunafish sandwich and eat.” Some read as poetry, others are matter-of-fact. With these ‘instruction pieces’, Ono invites the viewer to perform the gesture she proposes, stepping back so that another may come forward to take her place. Even when the artist is bodily present, as in the performance Cut Piece (1965), she remains impassive; allowing her clothes to be cut away, the piece to continue on to its conclusion. Her work is coloured by this quiet contradiction: the precision of her propositions and her commitment to letting go.