Binelde Hyrcan

Chauffeur, go faster!

I’m getting tired.

Chauffeur, don’t talk, just drive!

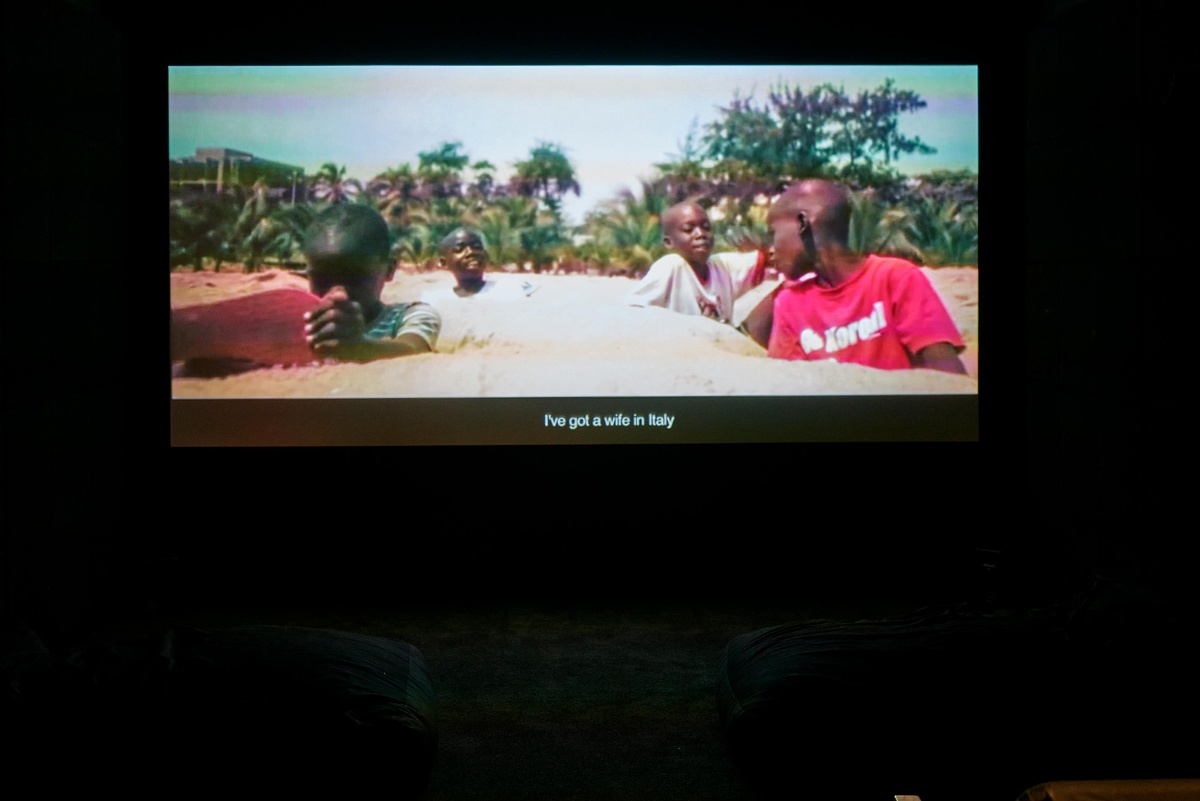

These English subtitles accompany Hyrcan’s short film Cambeck, which features four young children on a beach in Angola playing at big shots and servants. For a vehicle, they’ve dug themselves into the sand. Equipped with meagre props – a flip-flop for a steering wheel, a sea view – the scene contains multiple readings. In one, it’s a playground-paradise, the children’s agency apparent in ‘making-do’ while ‘making-it-up.’ In another, they yearn for an imagined elsewhere possessed of riches and resources, in rapid dialogue:

Your father is the doctor

He’s taking me to America, to live in a building.

The conversation progresses in Portuguese, the highest pitched voice of a small boy features the loudest (he’s the boss, plays the wealthy man shouting at the driver). The phrase, The good life is said in English. In Brazil, they get around by planes, it’s not like in here, there’s no shitty car like this one. The chauffeur of the shitty car keeps his eyes on the road in spite of the cruel comments levelled towards his vehicle, not once taking his eyes from the horizon line over the ocean, or ceasing to push at his steering wheel. The children’s play features the polarity acted in so many childhood games. Think cops and robbers, the multitude of ‘goodies vs. baddies’ characters that populate these imaginative processes. Present too is the ambivalence, even rogue sensibilities children reveal when taking on these roles. Who is the hero? Cop or robber? The rich man hurling abuse at this driver, or the abused?

b.1983, Luanda

Binelde Hyrcan is the youngest child of thirteen. This must in some way account for the feeling of free-play which characterises much of the artist’s work. Mischief, games, a puckish caper; the fun of Hyrcan’s practice contains a strong kick, as if used to the myriad humiliations that only siblings can exert on one another underwritten by the insurance of affection. In his performance works and films, Hyrcan creates a theatre of absurdity, a biting comedy. In White Rain, he sat under a tree opposite a state building in Luanda. The tree’s inhabitants – a multitude of birds – repeatedly shit on him. In Monaco, from inside a cage, he proclaimed himself ‘King’, ordering passersby to push him around. “We will repaint the world,” writer Jean-Baptiste Gauvin quotes Hyrcan as saying. The backdrop to Hyrcan’s childhood was the Angolan Civil War, a twenty-seven-year conflict which displaced over a million people. Movement – the freedom to move, attendant themes of migration – is a recurring thread in Hyrcan’s work. In 2020, finding himself in isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic due to mandatory quarantines placed on citizens worldwide, he created life-size ‘puppet friends’ and posted videos on Instagram, drinking wine with one, exercising with another. As soon as restrictions were lifted, he began a solo walking journey from Paris to Lisbon along the coast in the manner of religious pilgrims. Hyrcan pokes fun at entrenched ‘pecking orders’ and calls out hypocrisy, while remaining committed to play.