David Goldblatt

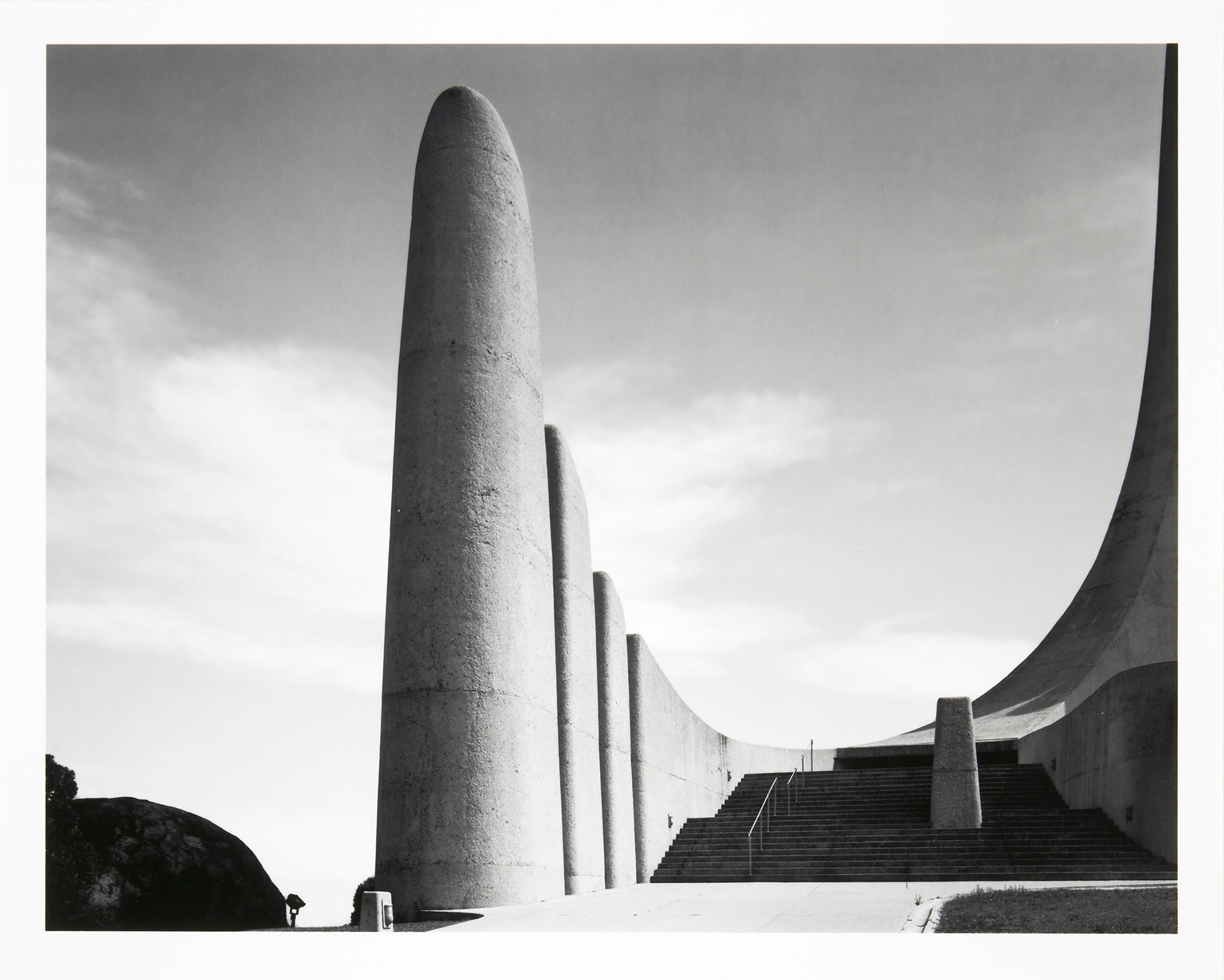

“Static structures, even the most confused, have a logic,” Goldblatt wrote, “find that and there will usually be one point from which to see the essentials of the whole.” That each site has a single authoritative view, a definitive vantage that offers a summary not only of its spatial implications but also its ideological inferences, is a premise elegantly expressed in The Structure of Things Then (1998), the essay in which this photograph was first published. Designed by architect Jan van Wijk, the Taalmonument – or Language Monument – is a secular folly commemorating the semicentennial of Afrikaans as an officially recognised language, and the 100th anniversary of the founding of Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners (Society of Real Afrikaners), which was instrumental in formalising and promoting it. Pairing Brutalism’s rough aggregate and cement construction with formal abstraction and didactic symbolism, the monument features a curved ‘bridge’ and ascending spire around which all its other elements are arranged. The former was inspired by renowned poet Nicolaas Petrus van Wyk Louw’s description of Afrikaans in a 1959 essay, Laat ons nie roem nie (Let us not boast), as “a bridge between the enlightened West and magical Africa.”

Flanking the stairs that lead to the structure’s entrance, three columns of diminishing height – representing, as per the brochure, “the languages and cultures of Western Europe” – assume a dominating presence in Goldblatt’s photograph. A fourth, much smaller column set in the middle of the staircase is symbolic of “Indonesian languages and dialects (mainly Malay)“. Absent from the image are three low convex forms representative of “Khoi and other African languages”. The apex of the central spire, cropped from view, continues to rise invisibly upwards – emblematic of the “accelerated growth of Afrikaans".

In a 1994 interview excerpted in the extended caption accompanying this photograph, van Wijk maintains that the structure was not informed by the prevailing ambitions of Afrikaner nationalism. “This monument is solely for the Afrikaans language, no matter who speaks it. It’s for a language spoken by 14 million people, of whom only 4.5 million are so-called Afrikaners, white people like me.” Goldblatt’s framing perhaps suggests otherwise.

b.1930, Randfontein; d.2018, Johannesburg

“I was drawn,” the late photographer David Goldblatt wrote, “not to the events of the time but to the quiet and commonplace where nothing ‘happened’ and yet all was contained and immanent.” A preeminent chronicler of South African life under apartheid and after, Goldblatt bore witness to how this life is written on the land, in its structures or their absence. Unconcerned with documenting significant historic moments, his photographs stand outside the events of the time and yet are eloquent of them. Through Goldblatt’s lens, the prosaic reveals a telling poignancy. Even in those images that appear benign, much is latent in them – histories and politics, desires and dread. His photographs are quietly critical reflections on the values and conditions that have shaped the country; those structures both ideological and tangible. Among his most notable photobooks are On the Mines (1973), Some Afrikaners Photographed (1975), In Boksburg (1982), The Structure of Things Then (1998), and Particulars (2003).