Bas Jan Ader

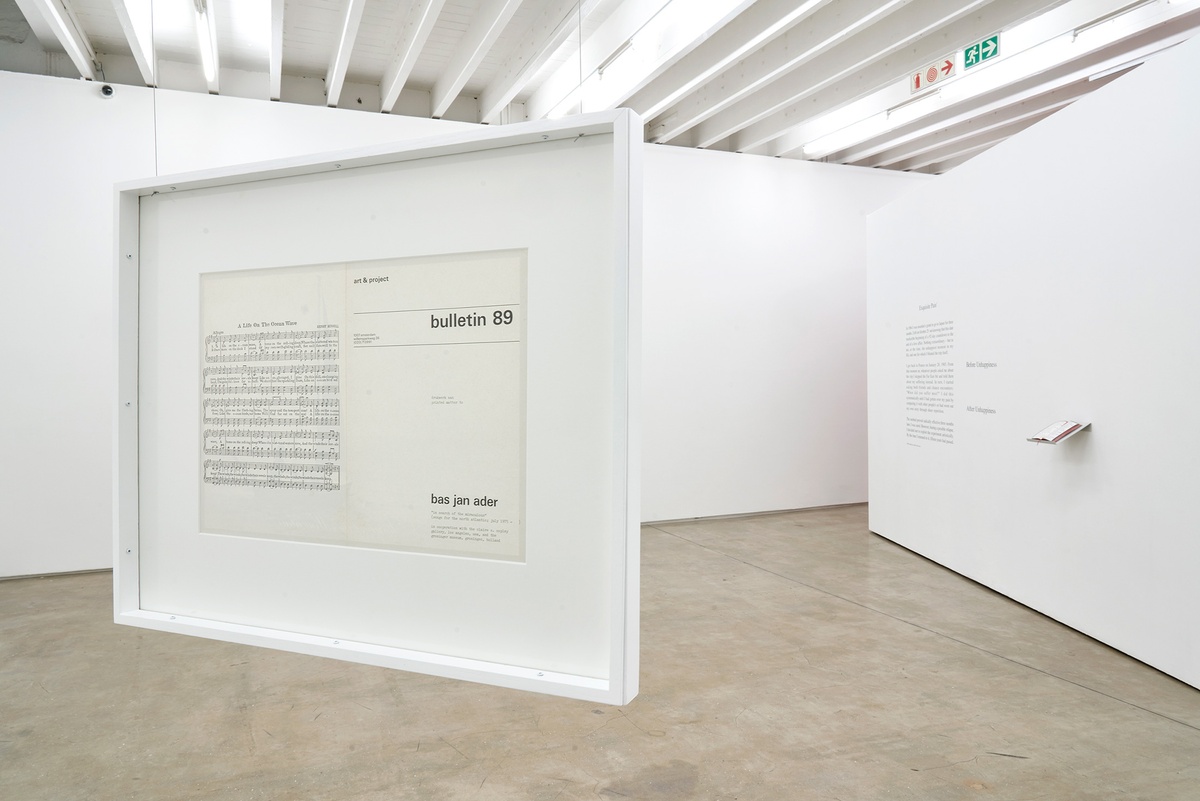

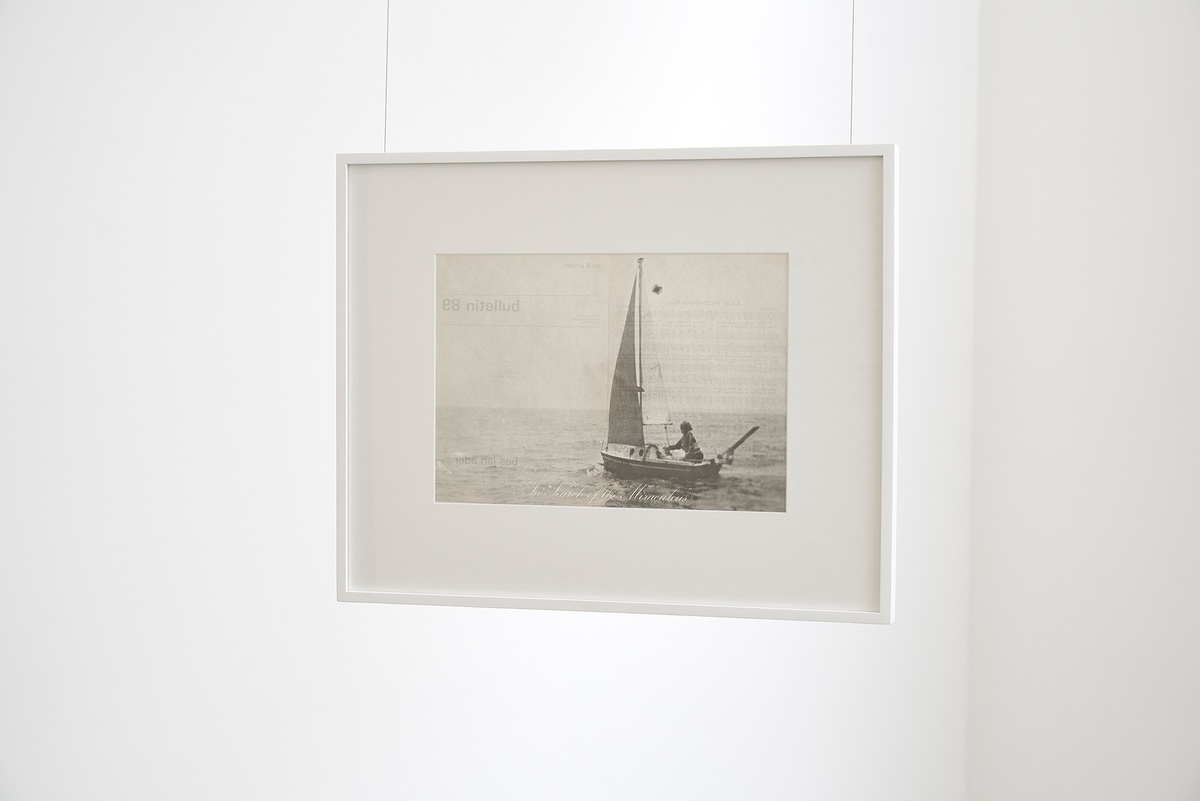

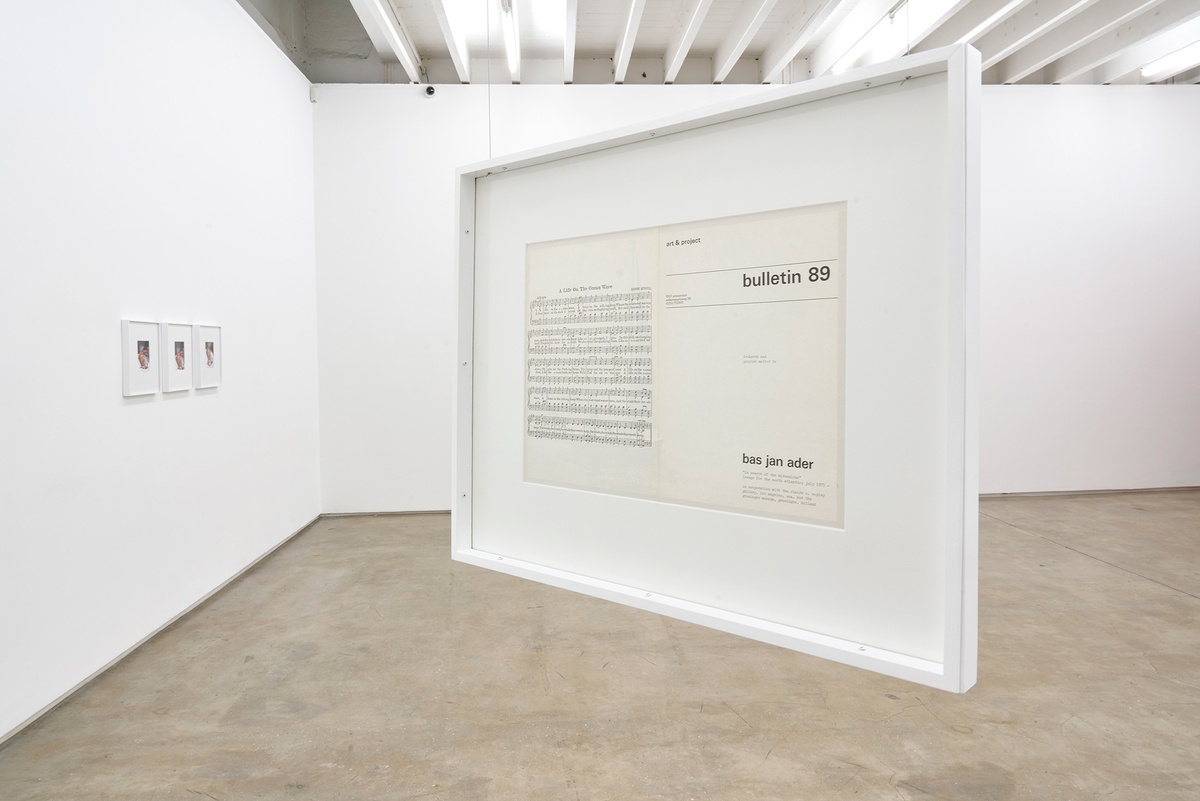

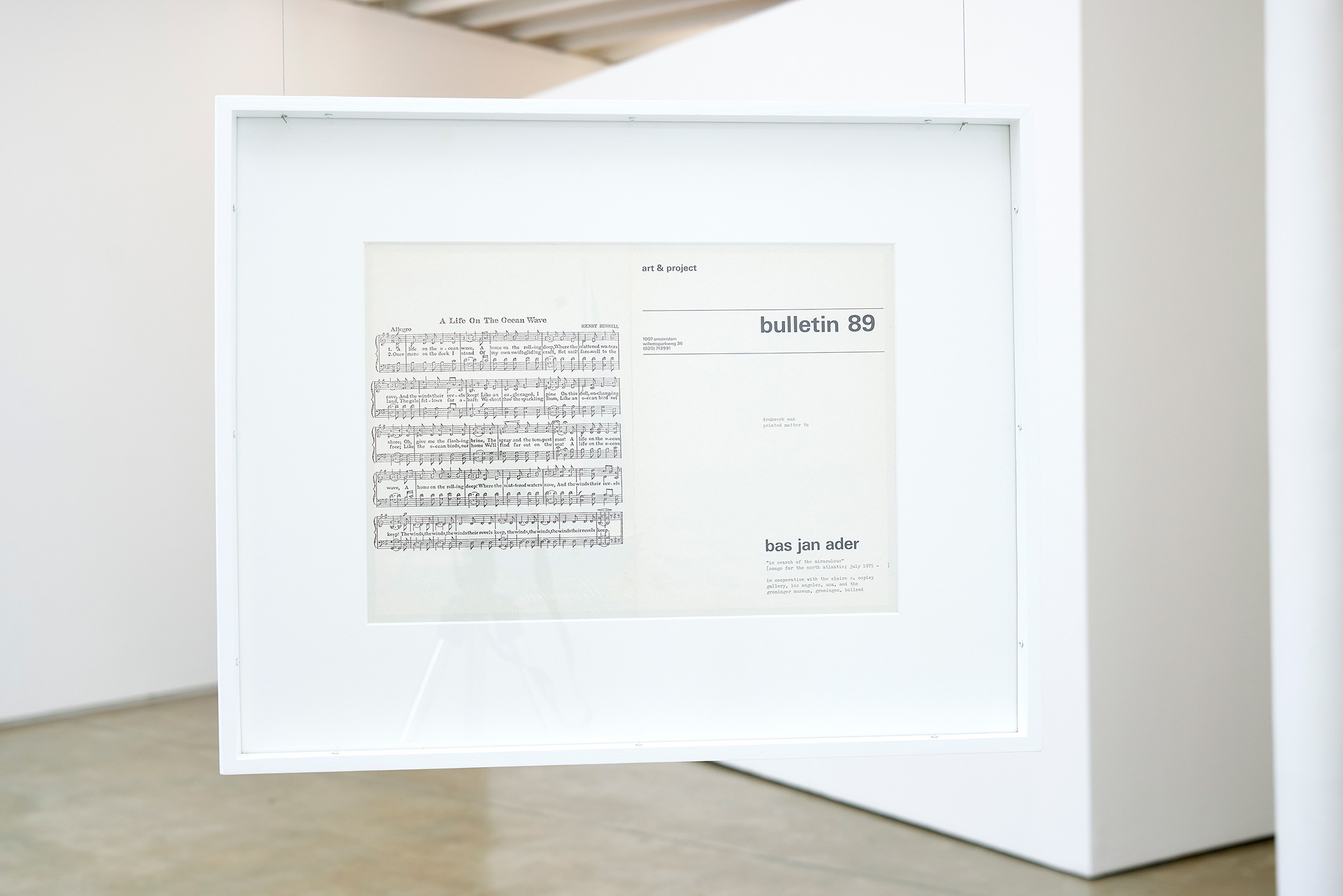

When In Search of the Miraculous (One Night in Los Angeles) was first exhibited, Ader displayed alongside it a bulletin published by Art & Project, an alternative art space in Amsterdam. The publication included the musical notation to a 19th-century sea shanty, A Life on the Ocean Wave (1838) by Epes Sargent and Henry Russell, as well as an image of the artist on a small sailing boat. The exhibition, held at Claire Copley Gallery, LA, was accompanied by a musical performance of seafaring songs. Together, the bulletin and shanties announced the artist’s upcoming gesture, the second in the In Search of the Miraculous series: Ader intended to set sail from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Falmouth, England, in a thirteen-foot vessel. The performance would last sixty days; the voyage documented in a logbook and photographs. On July 9, 1975, Ader sailed out into the Atlantic. His wife, Mary Sue Ader Andersen, photographed the artist as his boat was towed out from the harbour. Three weeks later, radio contact onboard Ocean Wave was lost. On April 16, 1976, the crew of a Spanish fishing trawler found Ocean Wave, bow submerged, the boat unmanned. That he disappeared in his search, rather than diminish the work’s success, has affirmed its lasting intrigue; the lone figure of the artist set adrift at sea.

b.1942, Winschoten; d.1975, Atlantic Ocean

Bas Jan Ader’s foundational works centre on a single verb: to fall. Following his relocation to America’s West Coast, the Dutch-born artist fell in with Los Angeles’ Conceptual art scene of the 1970s alongside the likes of Chris Burden and Jack Goldstein, with whom he shared a proclivity for precarious performances. The ‘fall’ works, which came to define his short career, distil Alder’s dedication to gestural simplicity, of action pursued to its logical limits. The artist falls from a roof, from his bicycle, from a tree branch hanging above a river – the performances compelling for the commitment with which the artist resigns his body to gravity’s pull. While parallels are often drawn between these performances and Buster Keaton’s deadpan acts, any humour in the ‘fall’ works is largely eclipsed by the violence of their fulfilment. Similarly opaque in their intentions, his proceeding works, which demonstrated less a fall than a falling apart, appear torn between self-seriousness and irony – the artist sends photographs of himself crying to friends, inscribes pop-song lyrics on pictures of late-night wanderings, proposes a work with the premise: “My body practising having been drowned.” This last has since gained the weight of prophecy. In 1975, Ader was lost at sea. His disappearance coincided with his final performance, the second work in a trilogy called In Search of the Miraculous. In death, Ader has become a modern-day myth: a tragic figure lost in pursuit of the transcendent. Popular imaginings, coloured by this romance, have further obscured the attitude with which his works were first conceived. The story of his death precedes his practice, circumscribing its resonances.