Jo Ractliffe

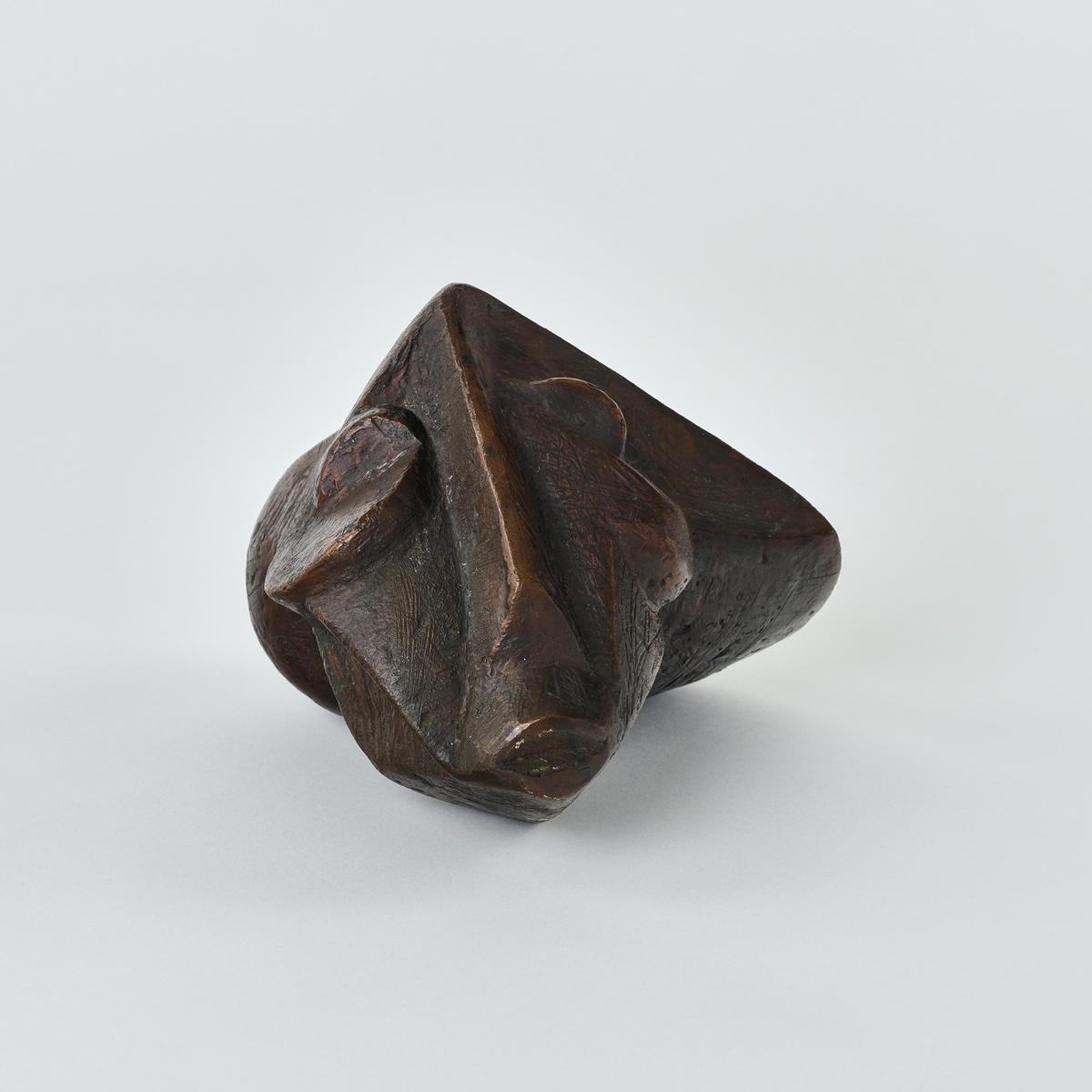

When Francisco Berzunza asked Jo Ractliffe to suggest an artwork to be included in You to Me, Me to You at A4, he had in mind a photograph Ractliffe had taken in Oaxaca of the curator standing together with his friend and collaborator, Dario Yazbek Bernal. Listening closely to what underpinned the proposed exhibition, Ractliffe instead brought out Love’s Body. Berzunza chose to place the work into a raised structure – reminiscent, perhaps, of a tomb. Above Love’s Body, he placed a photograph by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, and at the work’s back, Diego Rivera’s mural The Protestor as photographed by Tina Modotti.

–

An excerpt from a conversation with Jo Ractliffe (JR), Josh Ginsburg (JG), and Francisco Berzunza (FB), held in person and online in preparation for You to Me, Me to You, 1 June 2023:

J.R. He was only ten years old. It was inexplicable. I remember waking up in the morning, and he was lying outside on the stoep. He was dead. It was an incredible shock. And I remember that, within a few hours, he was buried. Stephen and his dad dug this big hole, and it was all over very quickly. I was never alone with him. I didn’t have that kind of moment, of parting... I suppose when you lose something or someone very special. He was so present in various parts of my life over the last ten years, spatially – the way that I moved in the house, in the garden, so much in my life was governed by his great big body. Even my work. I decided to photograph him. I’d always argued that photographs were fundamentally separate from the real. That the photograph couldn’t stand in for experience.

J.G. There’s something, formally, about this image with its blanket, that is particular. How was it constructed?

J.R. I photographed with a twin-lens reflex. And I’m above looking down, so I have to invert my camera. It’s almost shot upside down. And it’s a square format, which means it’s quite balanced in that way, centralised. It’s shot on slide film, which has a much more saturated colour. And there’s that Joburg red earth, which has a very particular quality. It’s quite lush in that way – a kind of visceral red, that Joburg earth.

J.G. The image, in some way, allowed you to let go of Gus, knowing you had something to carry, to show others.

J.R. What I was doing wasn’t very different from the ways that people have long dealt with grief, particularly in the early days of photography. It was quite ordinary – though maybe not so much now – to photograph your dead… It’s a way of thinking about the photograph, not simply as a transcription of something but as an actual material object. It’s like the wafer and the wine, which stand in for the body and blood of Christ. Here’s a photograph that stands in for the body pictured. The photograph starts performing or enacting something. It was a different way to think about what photographs do. They are material objects that have a force; they assert themselves.

J.G. Did it change the way you took photos?

J.R. No, not necessarily. But it changed the way I thought of photographs and death – the understanding of the photograph being tied up with death. It actually shifted that. I don’t think that all photographs are memento mori simply because they’re always about the past, and the past is irretrievably gone. I think photographs are distinct from their referent or subject. They enter a present as their own object. Curiously though, I have never actually printed this photograph. It’s presented as a lightbox. So it’s remained a spectral thing, a kind of emanation of something, ghostly – disembodied.

b.1961, Cape Town

To Jo Ractliffe, photography is “largely about guarding against loss,” of giving to memory an image, that it might be kept safe from forgetting. Her photographs more often speak of events past, considering the traces southern Africa’s recent conflicts have left on the land. She returns time and again to Angola, which remained at war for twenty-seven years, from the War of Independence, beginning in 1961, to the end of the Civil War in 2002. In 2007, she visited the country for the first time. “Until then, in my imagination,” Ractliffe writes, “Angola had been an abstract place…it was simply 'the border'. It remained, for me, largely a place of myth.” Absence is inscribed into all her photographs of that country, absence and the persistent presence of war's aftermath. More often, her titles alone establish their significance. Dusty landscapes are revealed to be minefields; rocky outcrops, the sites of mass graves. The atrocities of the past, now mute, are evoked in the bleak emptiness of the scenes she pictures. Ractliffe, preoccupied by all that photography necessarily leaves out, considers silence implicit to her medium. “I try to work in an area between the things we know and things we don't know, what sits outside the frame…these oblique and furtive ‘spaces of betweenness’.”