Sophie Calle

Thirty-six days ago, the man I love left me. It was January 25, 1985, at two in the morning, in room 261 of the Imperial Hotel.

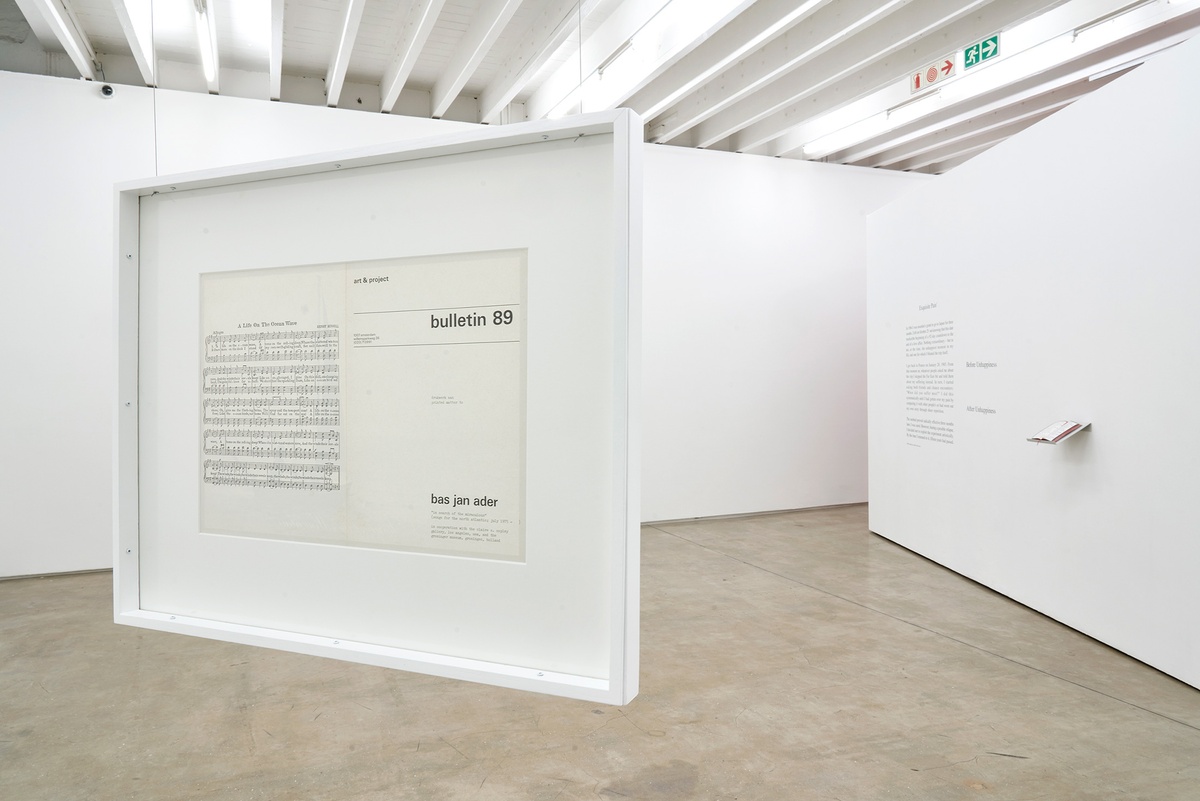

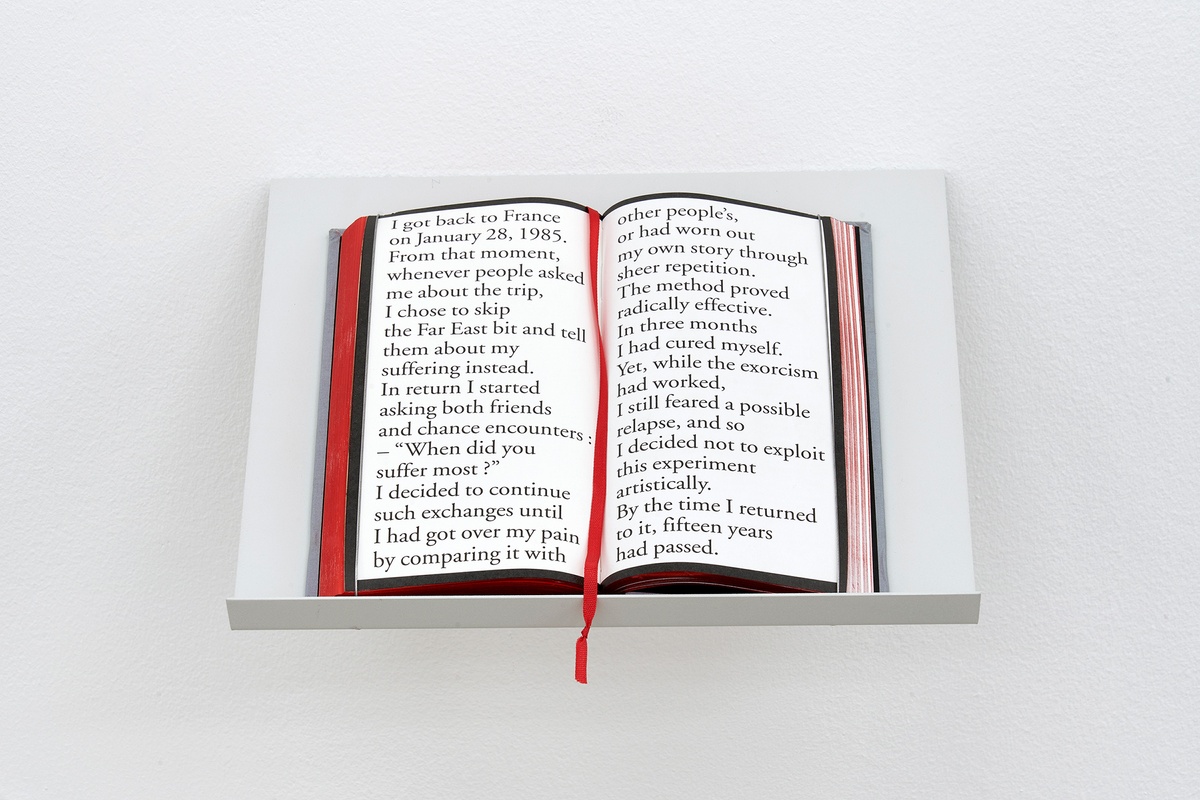

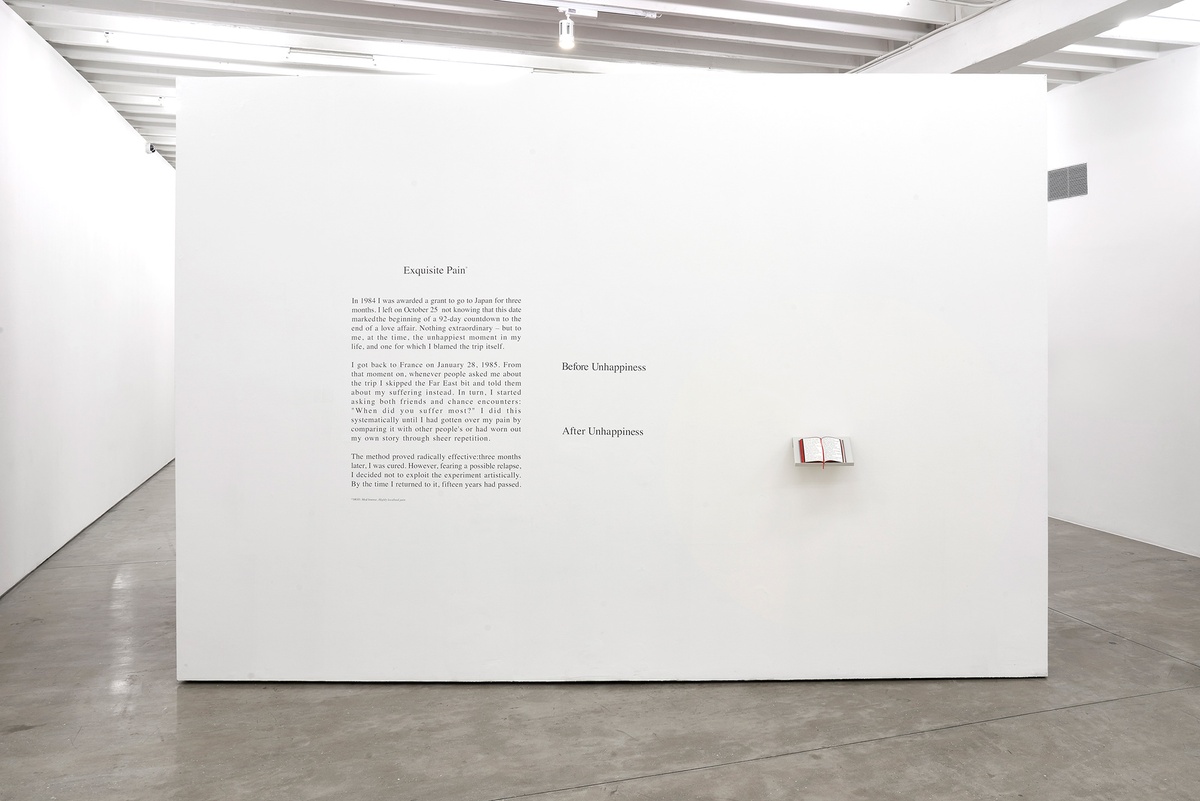

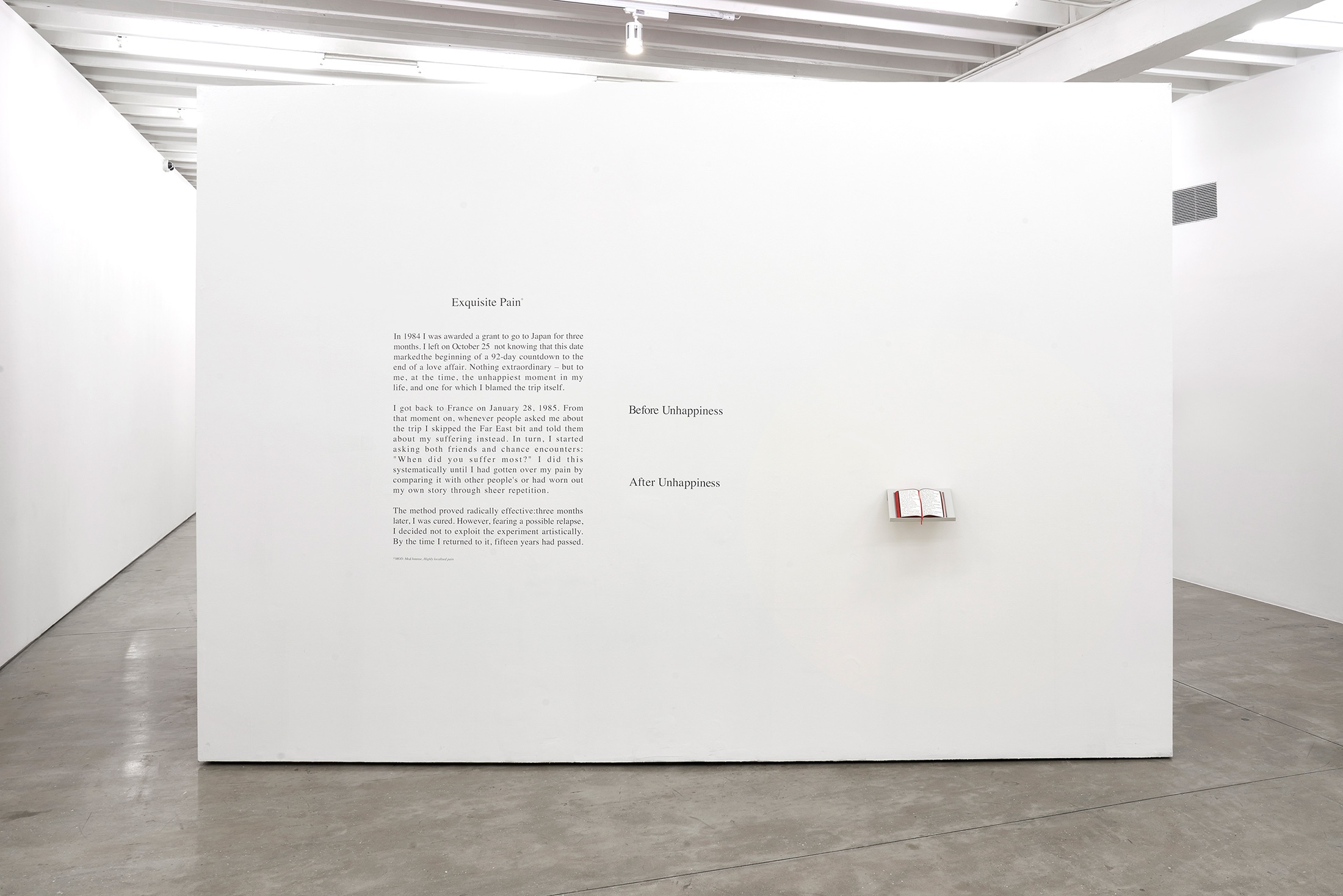

So begins Calle’s Exquisite Pain, a work that extends personal grief into collected reflections on love and loss. The work proceeds towards a rupture; for ninety-two days, the artist awaits the arrival of her lover, recording her happy anticipation in a series of photographs. The day arrives. He fails to appear. The relationship ends (over telephone, across continents). Heartbroken, Calle recounts the subject of her grief to anyone who will listen. In turn, she asks each listener, “when have you suffered the most?” The resulting exchanges, accompanied by images, comprise the book’s final thirty-six spreads. On each: two texts – the artist’s and the stranger's – and two photographs. Narrating and re-narrating her grief, Calle attempts an escape from her mourning. For sixty days, she repeats the story of her heartbreak. Writing on the fifteenth day following the rupture, Calle says: “He’s the one I want to talk about. Until I’m up to here with him. Disgusted. He’s the one I have to get rid of.” Witnessing the suffering of others becomes a balm to her grief – “they made my pain manageable” – a way out of heartbreak’s hold. Though perhaps self-interested, Calle’s mourning mechanism offers its participants both cathartic release and an object of safekeeping (a book) to house their pain. The viewer assumes the part of distant witness, watching at a remove the grief of anonymous others.

Excerpt from Sophie Calle, Sans Titre (2012), a film by Victoria Clay Mendoza with Sophie Calle (S.C.):

S.C. People think they know my life because I am always talking about it. But I do not feel like I am revealing anything.

My work is not a blog nor an intimate diary.

This happened, that happened but it is not The Truth. I have selected one moment amongst many others, separated it, given it importance and written it, generally it is just an ordinary moment.

We have all received a break-up letter, been left, felt lonely, I just use those moments for my work and to turn the situation around and distance myself from it.

Obviously I speak only of situations gone wrong.

Who wants to know I spent six years with a man that loved me and with whom there were no conflicts.

I live the happy moments, the sad ones, I exploit for artistic reasons, to turn them into a piece. Even if the starting point is therapeutic, the real reason is for the piece to end up hanging on a wall or be in the pages of a book.

b.1953, Paris

A certain slipperiness defines Sophie Calle’s practice, which turns on a singular, voyeuristic intrigue into the lives of others. Central to all her works is stated absence – of the beloved, of sight, of permission to intrude. The artist performs as a storyteller, spy and stalker, compiling intimate accounts of her subjects (who are more often unwilling strangers). The resulting narratives speak to loss, longing, and the opacity of selves other than one’s own. Missed connections offer a theme; suggested encounters fail to arise. A curious inclination to expose domestic privacy and an archival impulse to document – in words and photographs – directs her work and its indiscretions. Calle, disguised as a cleaner, photographs the possessions of guests in a hotel. She shadows a man to Venice and records his every movement unnoticed. An address book found in a street is returned to its owner but not before the artist has photocopied it; every contact later interviewed to form an impression of the stranger to whom the book belongs. Text is primary in recounting these encounters, the artist distilling her transgressions in lyrically spare prose. Calle maintains a distinct distance from her stated subjects – even her own heartbreak and the death of her mother – framing her vulnerabilities and those of others with studied detachment.