Sabelo Mlangeni

From the series Isivumelwano, 2003–2020

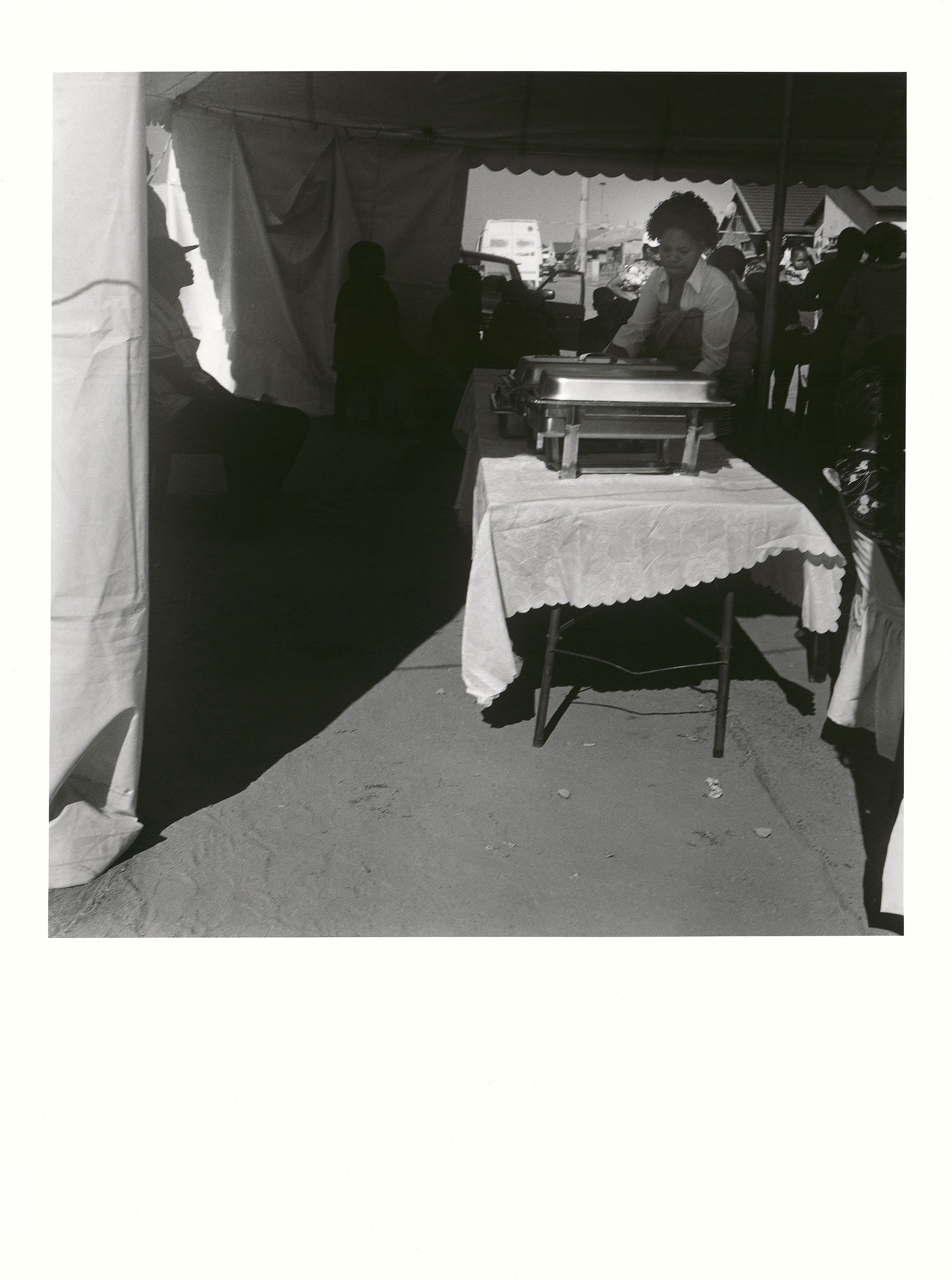

“The camera’s intervention reveals the ritualistic work of love – in these works, it is a formal act that drives cultures from subjugation to celebration,” says Emmanuel Balogun of Isimvumelwano. “The Nguni word, isivumelwano, represents a contract, agreement or alliance. In Sabelo Mlangeni’s context, Isivumelwano is a cause for celebration and critique of the relationships we keep with others.” In this series of wedding photographs spanning nearly 20 years, Sabelo Mlangeni documents moments of informality seldom seen in staged wedding photographs – empty chairs; silvered catering containers; a bride, Xhikeleni, and her husband, Rafito, his likeness halved by the image edge. Mlangeni often divides his images in two, obscuring figures in darkness. Through imperfect images, he betrays both his photographic precision and position within the scenes pictured – he is a part of the procession, at once observer and participant. A maker of deeply etched snapshots, Mlangeni makes visible the power of marriage in shifting communal boundaries and loyalties.

b.1980, Driefontein

Sabelo Mlangeni’s photographs offer intimate insights into the lives of others. He takes as subject expressions of community – be it chosen or happenstance – from a poor, historically-white suburb in Johannesburg to migrant workers living in hostels, Christian Zionist church groups and inner-city street sweepers. A sense of Mlangeni’s affinity with the people he photographs is apparent in all his work; a sense of his being present in the photograph yet out of frame. His is not the lens of a voyeur, but rather one in close dialogue with those he pictures, wary of the tropes of poverty and otherness to which the documentary medium plays. Bongani Madondo writes that “Mlangeni is ill at ease with referring to his work as ‘art’, or to himself as a ‘photographer’, preferring instead the term ‘cameraman.’ It might be most accurate, though, to say that he is a street photographer in the most historical sense, the ultimate flâneur – to wit, an [Eugène] Atget of Johannesburg.” Each photograph is a tender reflection on selfhood and community, on what it is to be both a part and apart.