Shilpa Gupta

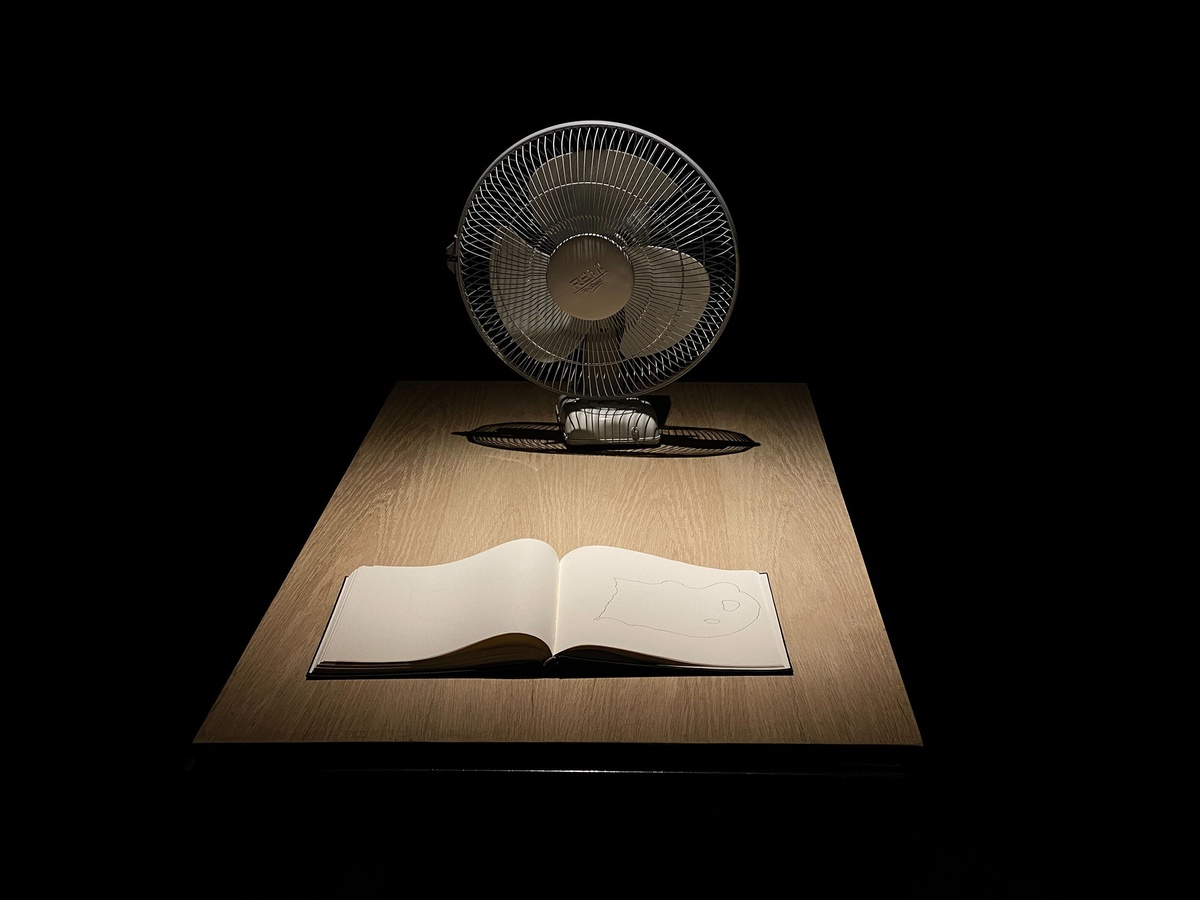

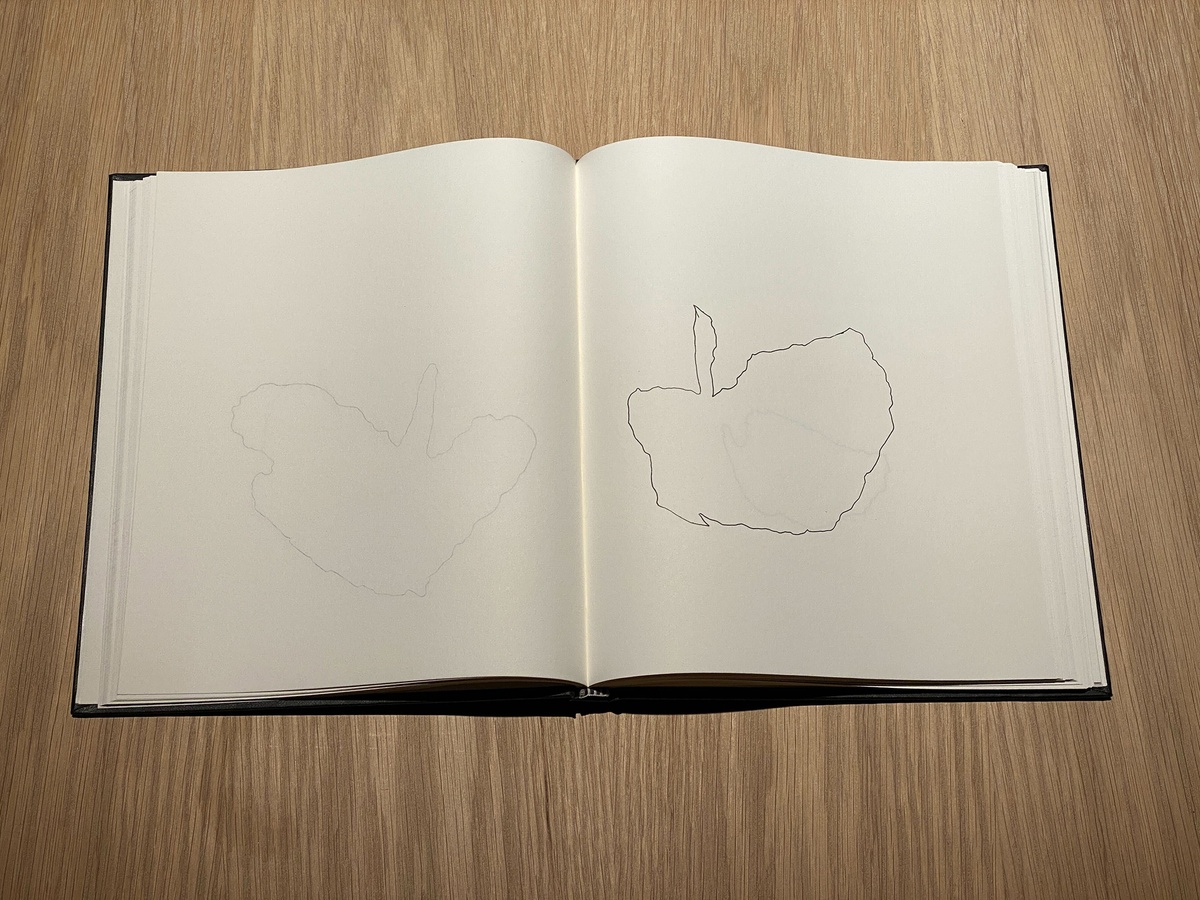

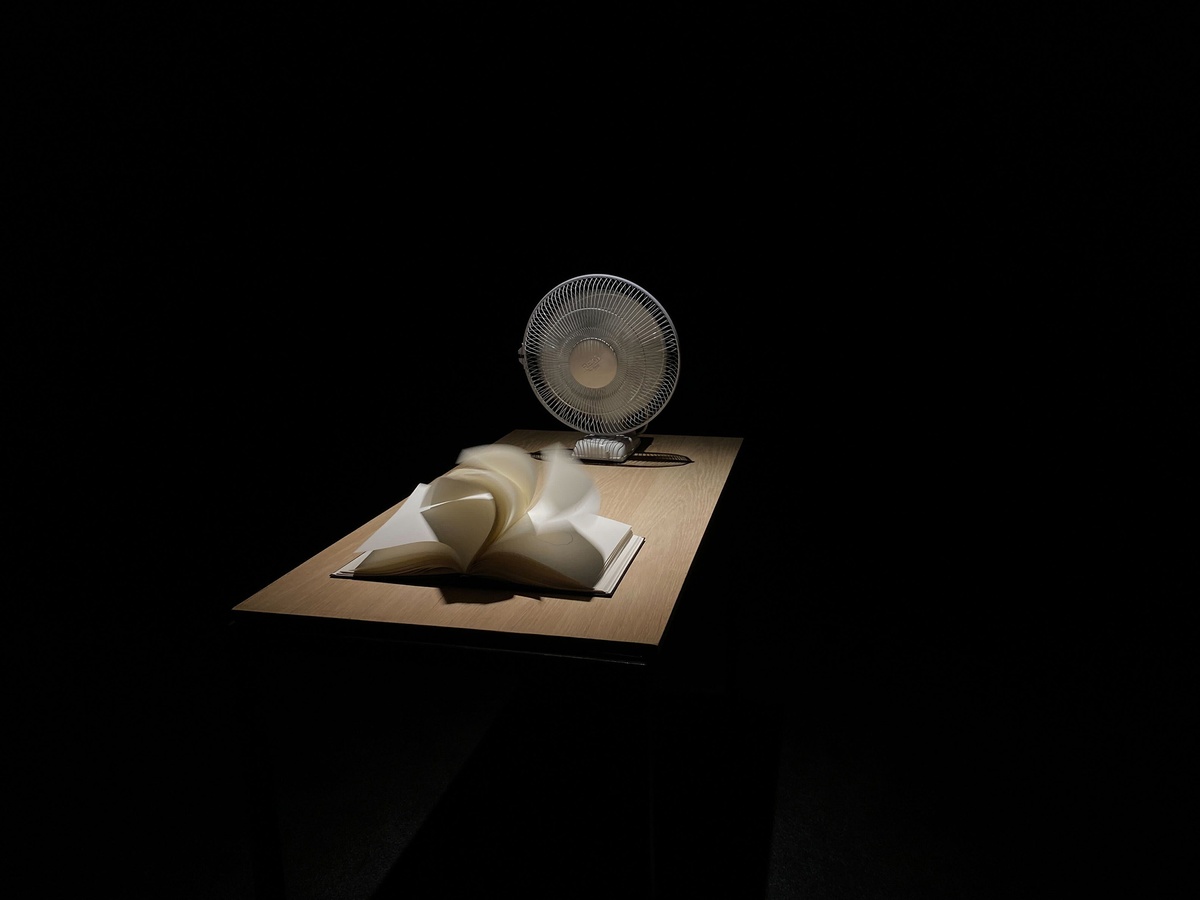

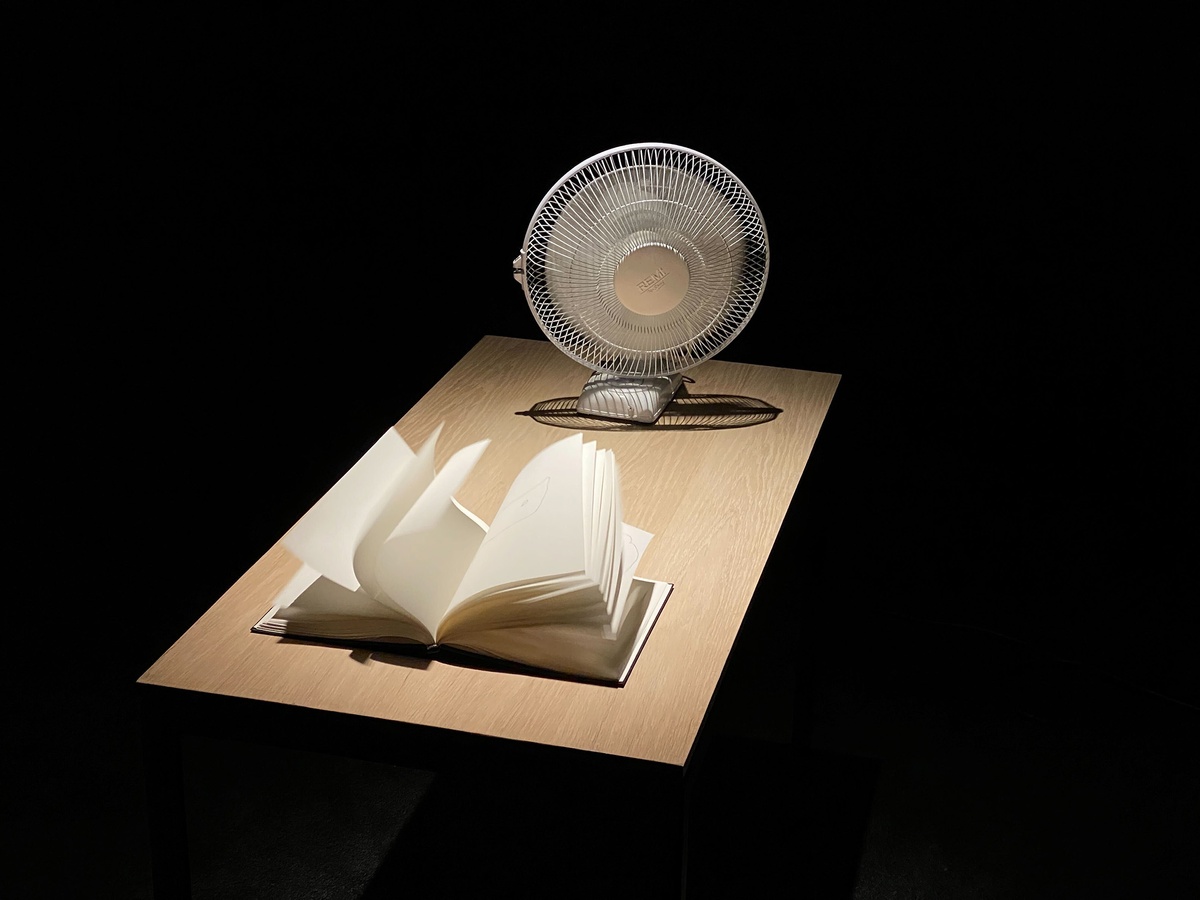

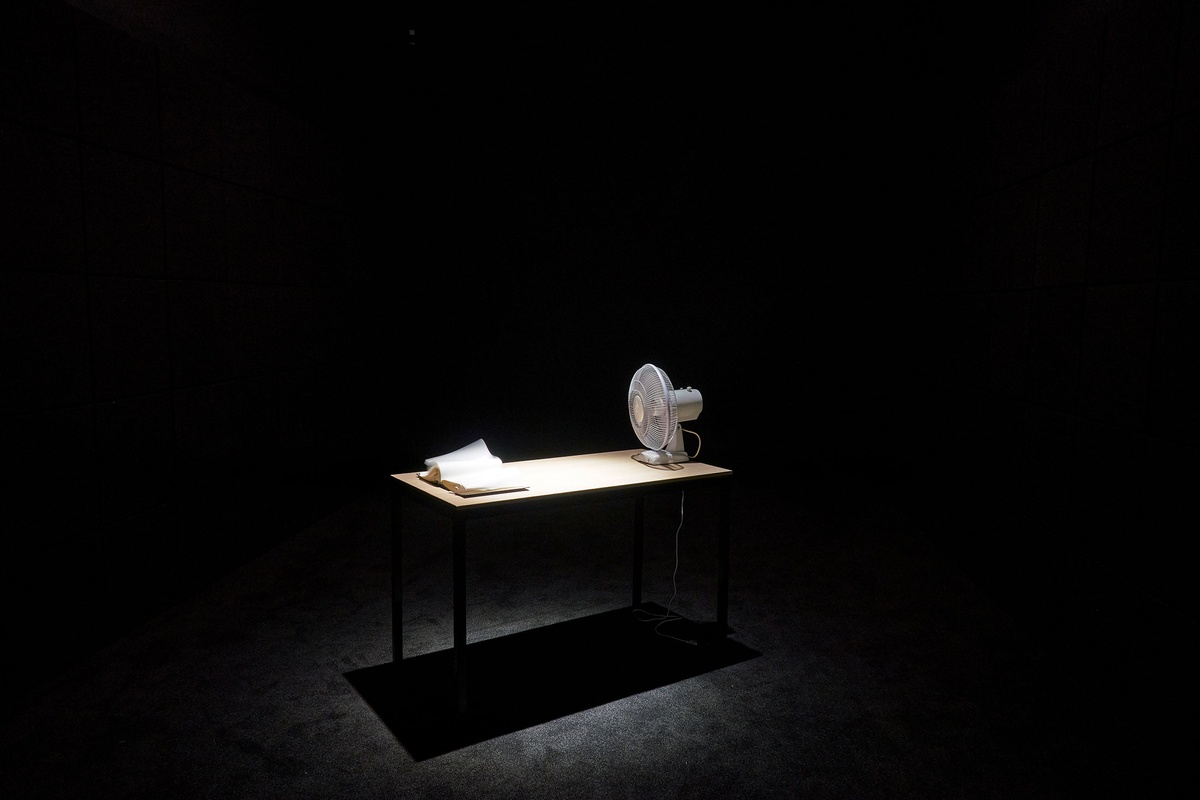

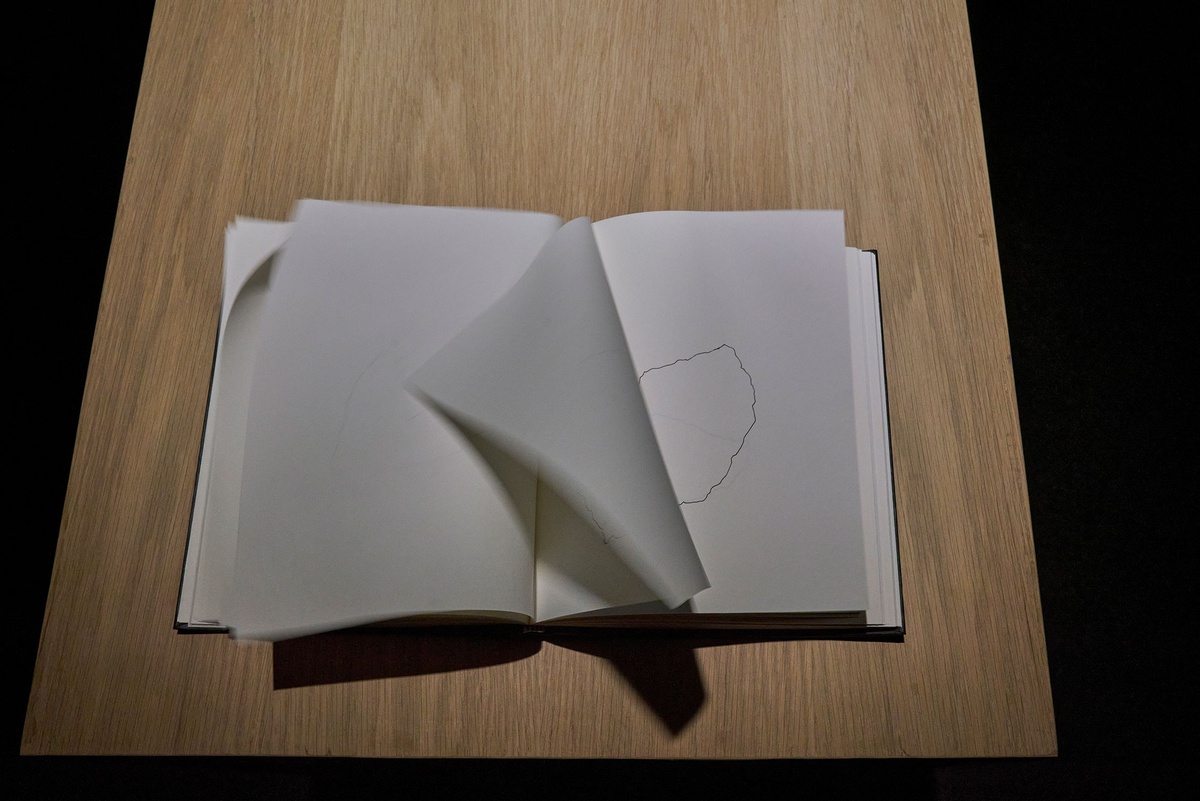

Begun in 2008, Shilpa Gupta’s ongoing series 100 Hand-drawn Maps explores the vagaries of discrete national geographies. The work begins with a request: a hundred people from a given country are asked to draw from memory its outline. These collected sets are differently compiled – in some, the drawings are traced onto one another to become a single, layered image; in others, they are traced into a book later set before a table fan, its directed breeze paging through the various renditions. “It’s only when you see these shifts and alterations in the drawings that they evoke an emotional resonance,” Gupta says. “This brings forth a certain disparity between private and public memory, between the officially sanctioned cartography and the informal mental image one holds of their country.” National borders, while largely static, reveal themselves capricious in the minds of their populace. Their accumulation highlights the disparities between geopolitical divisions and imagined boundaries, revealing the similarities and divergences in our impressions of place.

For this edition of the work, 100 Hand-drawn Maps of South Africa, Gupta sent a blank notebook to A4 from her studio in Mumbai. The artist, through A4’s team, invited 100 people to draw an outline of South Africa’s borders inside this book. This map was to be drawn from memory (or, should memory not serve, using imagination). Participants were asked not to Google the country’s boundary and to resist the urge to peek at the previous drawer’s page. As far as possible, the outline was to be drawn in one continuous gesture. Upon receiving the filled book, Gupta traced each drawing. That book of her tracings stands on the table, the pages blown into disarray by a hand-painted fan, awakening the viewer to the handmadeness of all borders despite their pretensions of impermeability, legality, and fact. Borders shift on the whims of so-called leaders. Most boundaries are invisible, more are imagined. The sands shift, the claims multiply, and as the edges blur, so the line divides.

b.1976, Mumbai

In materially understated compositions, Shilpa Gupta attends to the hard edges of geopolitics – border walls, infrastructures of control, the physical limitations placed on bodies – as they play out in our imaginings of nationhood, sovereignty, and belonging. Pairing empirical data with formal lyricism, she asks after the more often insidious mechanisms of statehood. Gupta traverses diverse mediums with conceptual deftness, citing the Hindi expression ‘jugaar’ as her working principle: a way to innovate with and around imposed rules, rigid bureaucracies, and limited resources. National borders become tensile in Gupta’s hands, her various articulations of their forms calling their often intangible yet acutely felt presence into view. “These map lines have become so hard,” the artist says, “and they have not always been that way: since they were first drawn, they have been porous.” In many of the artist’s works, poetics rub up against impassive facts. In 1:14.9 (2011–12), a hand-wound ball of thread presented in a vitrine is accompanied by a small plaque that reads: 1188.5 MILES OF FENCED BORDER – WEST, NORTH-WEST / DATA UPDATE: DEC 31, 2007. The thread, appearing as an egg-like abstraction, assumes political resonance with this inferred context. Unspooled, it measures nearly one-fifteenth of the length of the borderline between Pakistan and India (the scale recalled in its title without geographic specificity), and gestures to broad political implications – among them, the South Asian partition in 1947 and present-day religious nationalism in India. Other similarly restrained works set commonplace materials and objects in relation to state borders, and still more ask after state oppression, military occupation, and censorship.