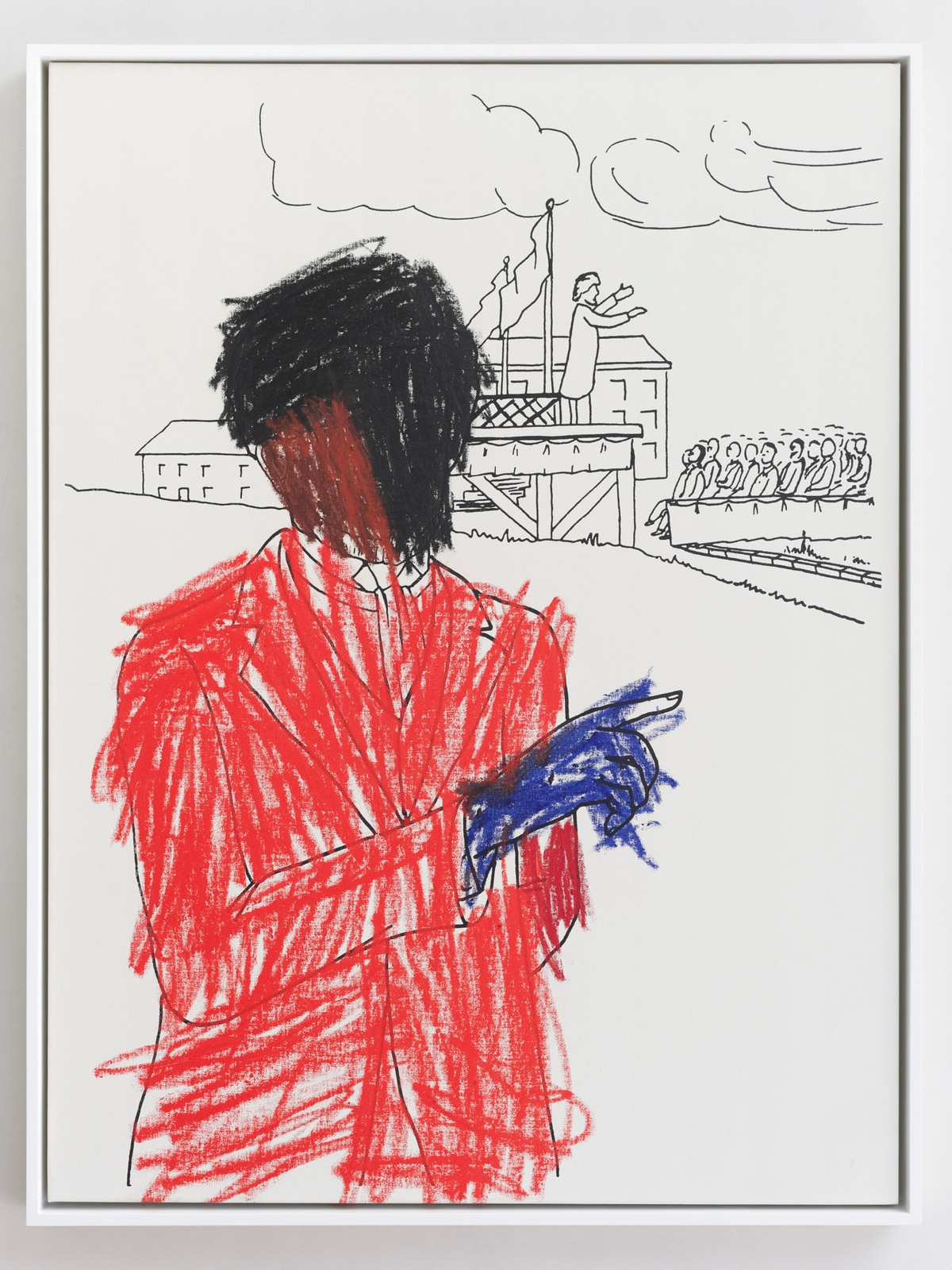

Glenn Ligon

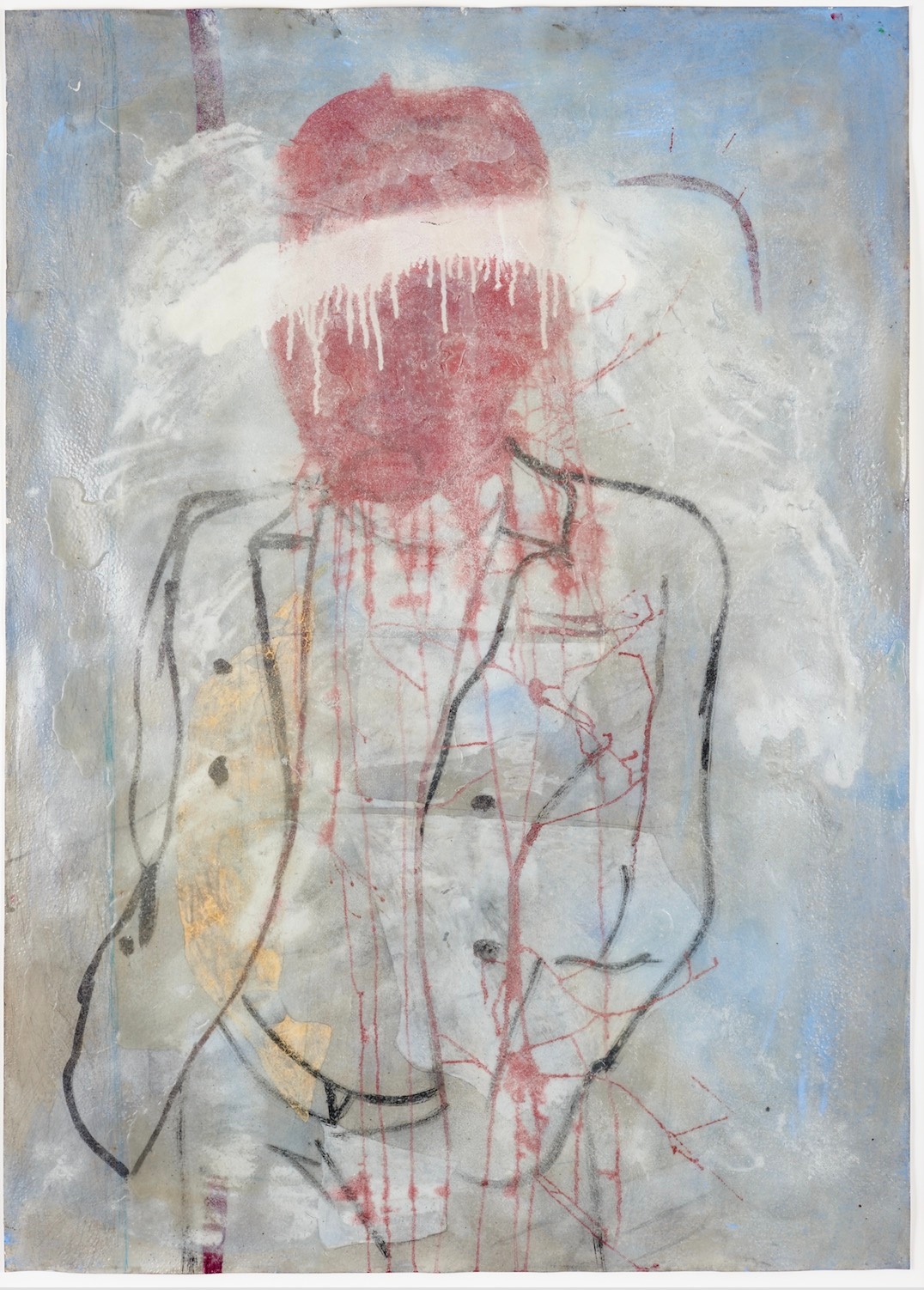

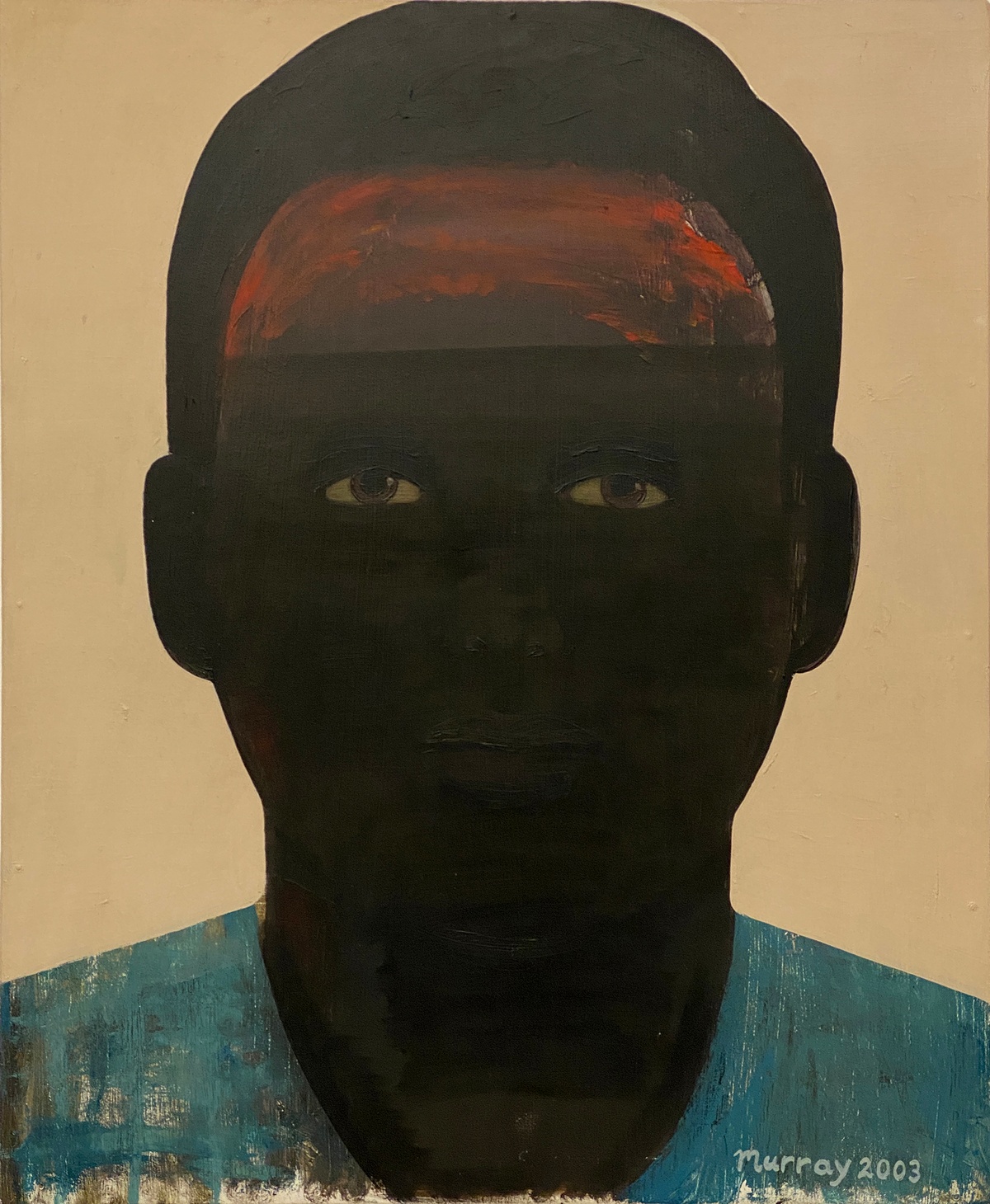

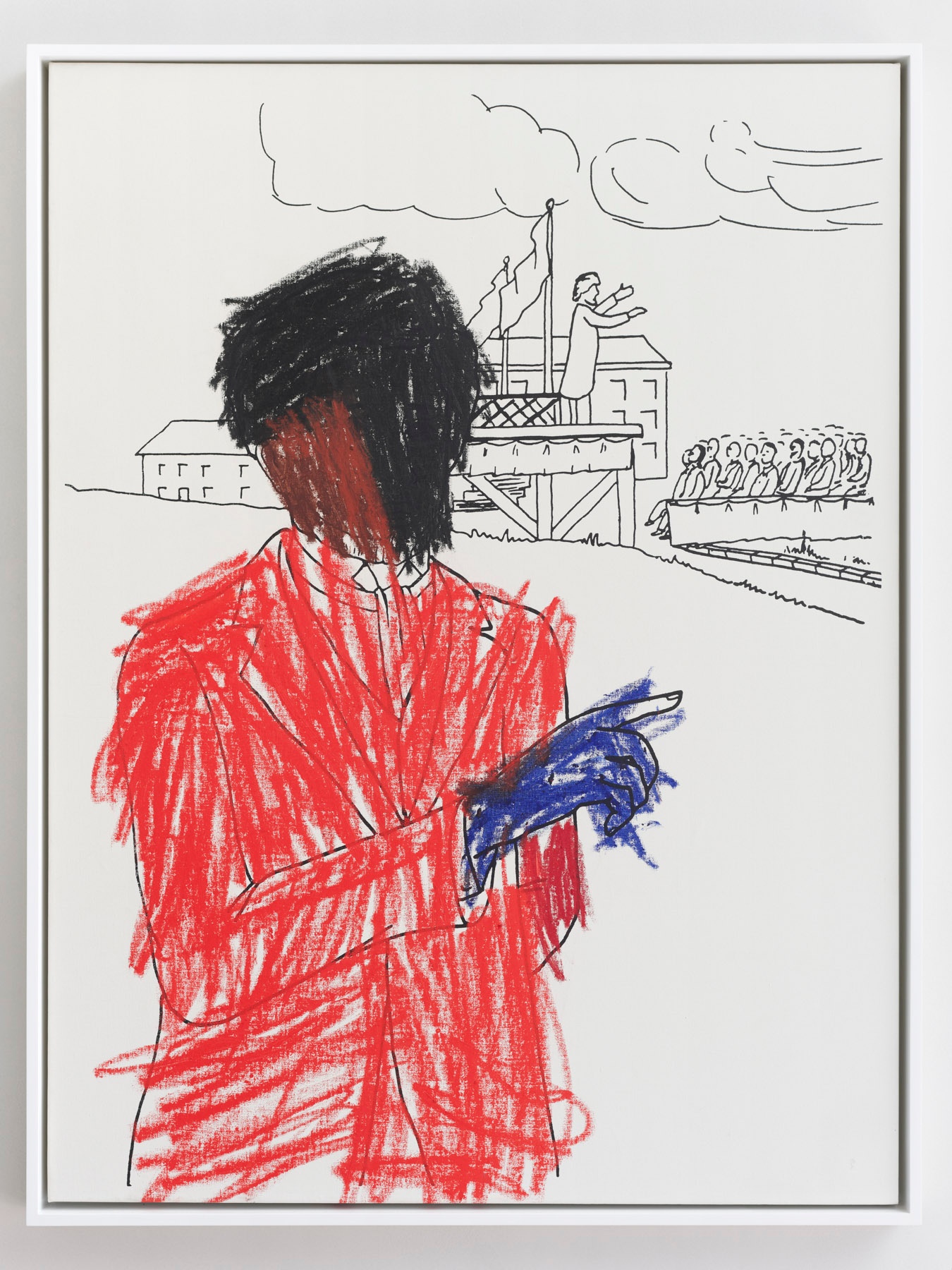

In Ligon’s Colouring series – to which Frederick Douglass (Version 1) No. 1 belongs – the artist reproduced drawings from Afrocentric colouring books published in the optimistic decade of the 1970s. Following the Civil Rights Movement in the USA, a political emphasis on the pictorial representation of black Americans saw the publication of many such pedagogical images. In a series of workshops, Ligon invited children to colour in drawings copied from such books. Most showed significant black American figures, such as Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X – though they largely went unrecognised by the primary-school participants. The irreverent scrawls and unintentional iconoclasm of the children’s crayons were later transcribed onto the artist’s canvas. “Ligon’s paintings,” art writer Liz Blackford suggests, “highlight the slippery nature of representation and the apparent desecration of these cultural icons... [H]e emphasises the unsettling extent to which the meaning of an image is socially determined.” The children, unconcerned with questions of identity politics, saw the images without the cultural and political import adults assign them.

Frederick Douglass (b.1818), for those unfamiliar with his name – children and adults alike – was an influential abolitionist and social reformer. An escaped slave turned statesman, he is remembered for his incisive antislavery tracts and autobiographical writings.

b.1960, New York

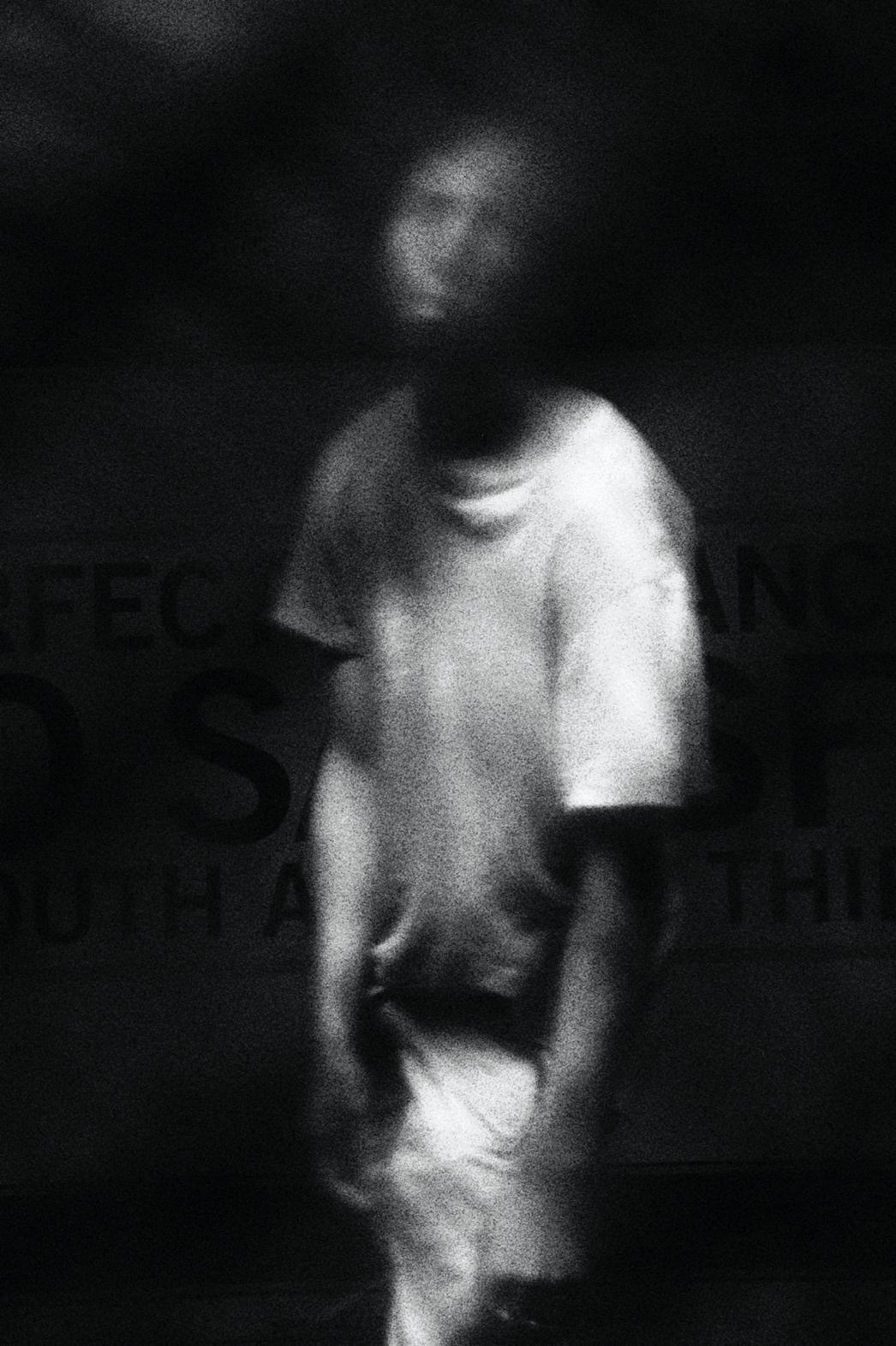

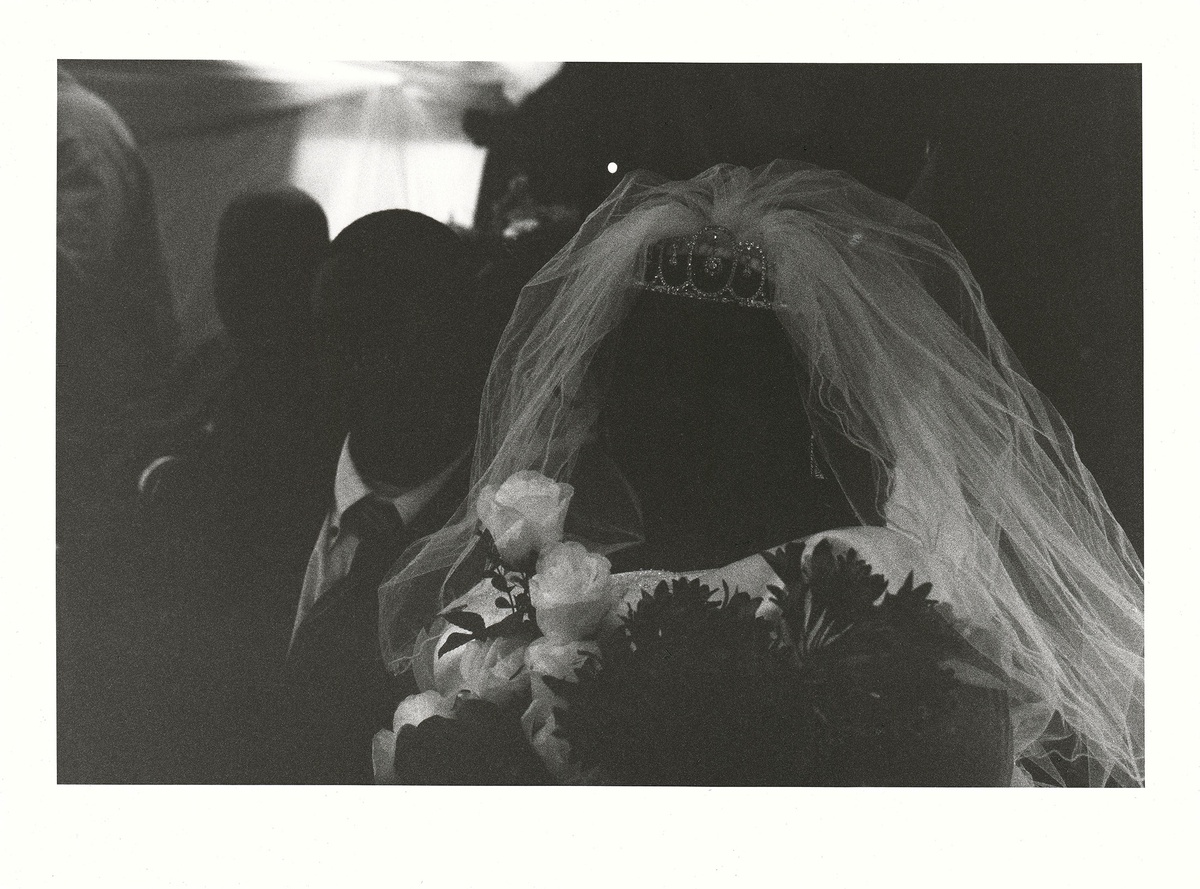

“Cultural translation, like any other translation,” the artist Glenn Ligon says, “is always involved with loss, the untranslatable, excess meanings, the indecipherable.” Recognised for his language-based conceptualism, Ligon’s practice cleaves cultural representation from its pictorial and linguistic signs. He works against the assumed legibility of black bodies to explore African American identity and queer sexuality, gesturing to the inadequacies of representation, to the imperfect translation of lived experience in image and word. He borrows widely from literature and popular culture yet disrupts the call and response these familiar quotations inspire, the recognition and implied meaning they have come to signify. Ligon invites the viewer to look again, to see anew, to re-evaluate the implications of these shared symbols.