William Kentridge

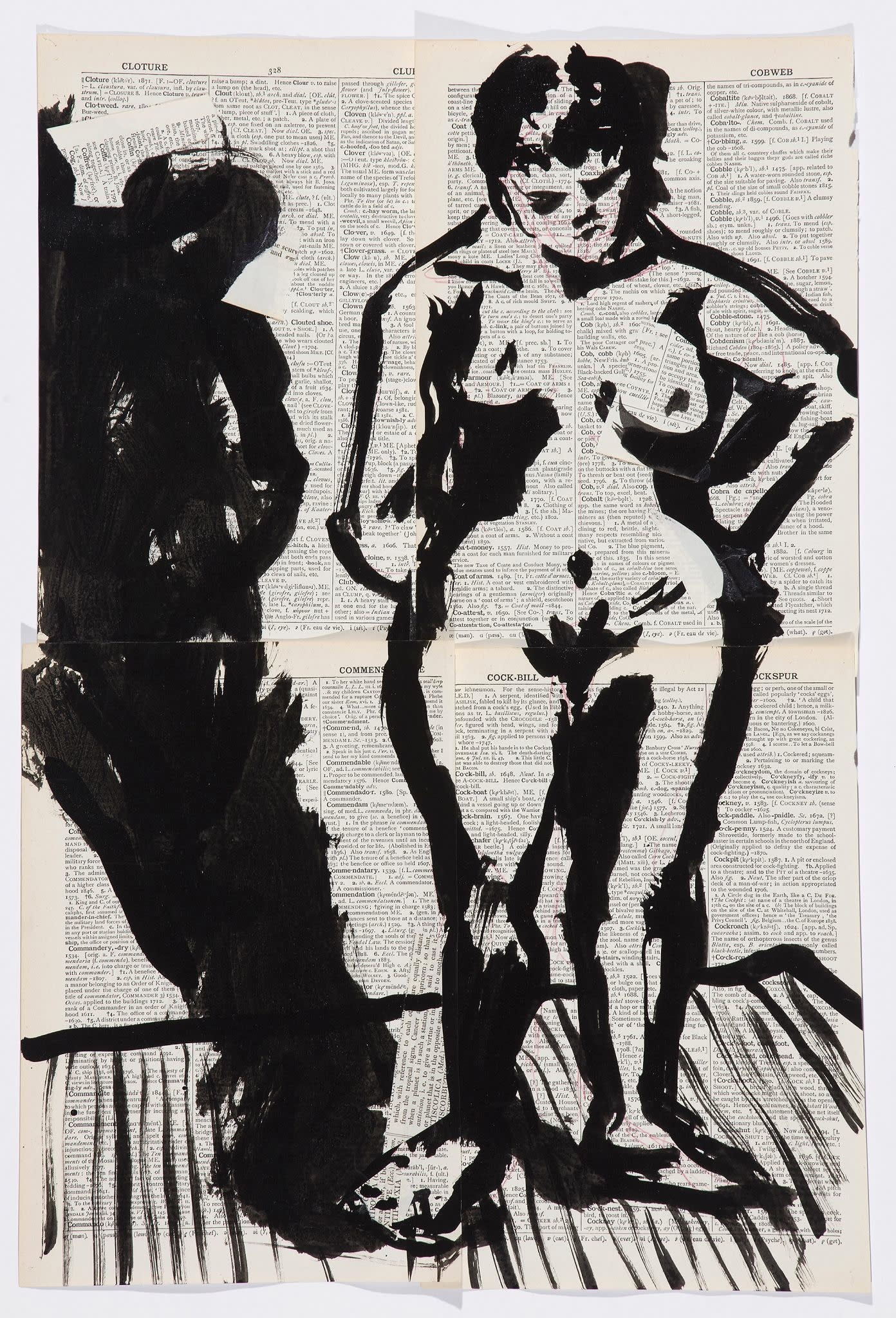

Drawn in ink on pages cut from the Shorter English Dictionary, Drawing for ‘Lulu’ is taken from a suite of illustrations made for Kentridge’s production of Alban Berg’s opera (1937/1979), which premiered at the Met in New York in 2015. Performed in the original German, the late-Weimar opera recalls the ill-fated femme fatale Lulu of the playwright Benjamin Franklin Wedekind’s Earth-Spirit (1895) and Pandora’s Box (1904). The opera’s twelve-tone composition and disjointed drama lend an unreality to Lulu’s downfall, as she rejects a series of lovers in scenes as atonal as the accompanying score –

Painter: I love you so.

Lulu: You reek of tobacco.

Painter: Can’t you speak with more warmth?

Lulu: I wouldn’t ever dare to.

Of the hundreds of drawings made for the production, Kentridge speaks to the physicality of ink, “black ink, ink as blood, the harsh lines and clarity of images corresponding to the ruthless world, becomes an aesthetic equivalent of the instability of desire, a central construct in the Lulu opera.” The drawings (later reimagined as set projections) are, the artist suggests, fragmented as desire is fragmented; the image of Lulu a mirage of imagined parts –

Lulu is both less and more than she wants to be, and more and less than her suitors imagine her to be. As such, she is often represented in a fractured formation in the drawings; constructed on multiple sheets; created to deconstruct and to fall apart.

b.1955, Johannesburg

Performing the character of the artist working on the stage (in the world) of the studio, William Kentridge centres art-making as primary action, preoccupation, and plot. Appearing across mediums as his own best actor, he draws an autobiography in walks across pages of notebooks, megaphones shouting poetry as propaganda, making a song and dance in his studio as chief conjuror in a creative play. Looking at his work, a ceaseless output and extraordinary contribution to the South African cultural landscape, one finds a repetition of people, places and histories: the city of Johannesburg, a white stinkwood tree in the garden of his childhood home (one of two planted when he was nine years old), his father (Sir Sydney Kentridge) and mother (Felicia Kentridge), both of whom contributed greatly to the dissolution of apartheid as lawyers and activists. The Kentridge home, where the artist still lives today, was populated in his childhood by his parents’ artist friends and political collaborators, a milieu that proved formative in his ongoing engagement with world histories of expansionism and oppression throughout the 20th century. Parallel to – or rather, entangled with – these reflections is an enquiry into art historical movements, particularly those that press language to unexpected ends, such as Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism.

Moving dextrously from the particular and personal to the global political terrain, Kentridge returns to metabolise these findings in the working home of the artist’s studio, where the practitioner is staged as a public figure making visible his modes of investigation. Celebrated as a leading artist of the 21st century, Kentridge is the artistic director of operas and orchestras, from Sydney to London to Paris to New York to Cape Town, known for his collaborative way of working that prioritises thinking together with fellow practitioners skilled in their disciplines (for example, as composers, as dancers). Most often, he is someone who draws, in charcoal, in pencil and pencil crayon, in ink, the gestures and mark-making assured. In a collection of books for which A4 acted as custodian during the exhibition History on One Leg, one finds 200 publications devoted to Kentridge’s practice. In the end, he has said, the work that emerges is who you are.