Santu Mofokeng

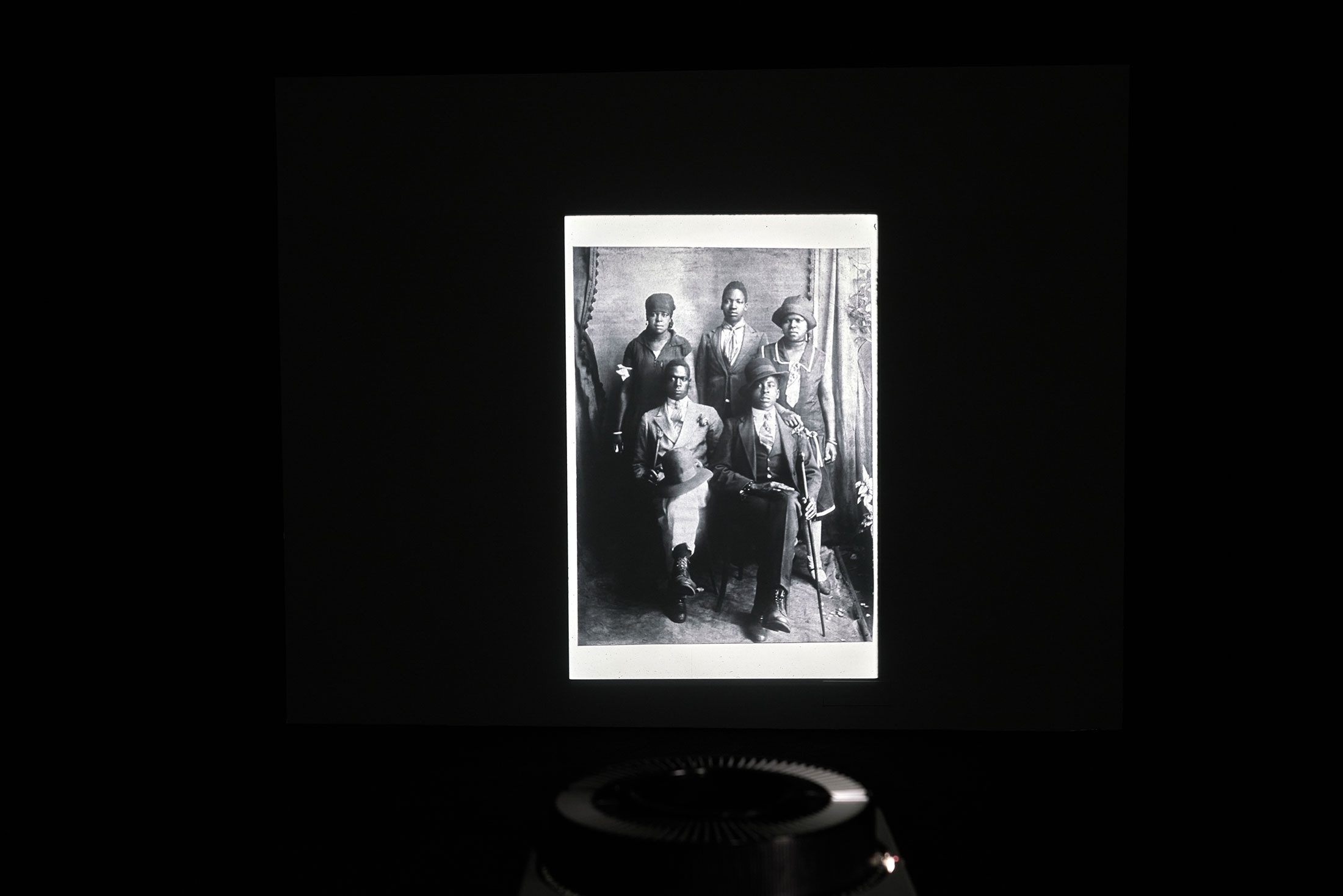

“Look at me,” Mofokeng’s Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950 prompts in a text slide, as the images begin to carousel. Interspersed with the photographs, text slides tell the family names, or those of individuals pictured, recollections from their relatives with whom Mofokeng spoke, and further challenges from the artist: “Who is gazing?”; “Who were these people; What were their aspirations, what is going to happen to those aspirations at the end of twentieth-century South Africa?”; “Are these images evidence of mental colonisation or did they serve to challenge prevailing images of ‘The African’ in the Western world?” Mofokeng liked best to have his own words accompany his work, disliking the mediation of exhibition texts and accompaniments provided by external writers. Of this project, he wrote, “The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950 is drawn from an ongoing research project. The project seeks to create an archive of images that black working- and middle-class families commissioned during the period 1890 to 1950 and the stories about the subjects of the photographs. Those of you with even a cursory knowledge of history will realize the significance of this period. While the world went to war twice during this time, South Africa was busy articulating, entrenching, and legitimating a racist political system that the United Nations later proclaimed, ‘a crime against humanity!’ In keeping with the theme of this analysis, I chose mostly those images that were made in the 1890s to 1900s and a few from the 1910s.”

b.1956, Soweto; d.2020, Johannesburg

“I am interested in the ambiguity of things,” the late photographer Santu Mofokeng wrote. “This comes not from a position of power, but of helplessness.” In many of his pictures, this ambiguity appears as a spreading opacity, a diaphanous pall of rising smoke, mist or dust. Mofokeng grew up, he wrote in his essay Caves, “on the threshing floor of faith…and while I feel reluctant to partake in this gossamer world, I can identify with it.” An agnostic observer attuned to the spiritual lives of others, the pervasive haze that softens so many of his pictures more often takes on a poetic significance. There is to all Mofokeng’s works a distinct quietude – the artist looking not to political drama but to life’s minutiae, those “things I ordinarily do or see.” The tumult of the times, Mofokeng believed, need not be made explicit in photographs. Rather, he suggested, “the violence is in the knowing,” latent in the very places and people he pictured. "His voice, his awareness of where he was in space and history, his ability to think around what he was doing,” Joshua Chuang said of the artist in conversation with Sean O'Toole at A4, “wasn’t predictable but open and raw and simultaneously hidden."