I visit Jared Ginsburg at his studio on a spring morning. There is a clean-edged crispness to the day: everything bright and clearly defined – the light, yes, but also sound. I notice the last in particular, the hum of heavy industry in the area beyond Atlantic House and the passing traffic on the nearby main road shifting into sharp clarity. Above this, a syncopated improvisation plays: car horns, an inconstant jackhammer, the repetitive cymbal of metal on metal. When I ask if I can record our conversation, Jared agrees only reluctantly. That the legibility of language sits uncomfortably with him is perhaps unsurprising to those familiar with his works on canvas – Jared has long made a practice of redacting or otherwise concealing the words he inscribes in paint. “I’ve found a way to make my utterances that is always ambiguous,” he offers in explanation. The space is largely empty of artworks when I visit, which seems to me further revealing of the artist’s effacing impulse. It isn’t – a body of work has recently left the studio for a show in New York.

The audio recording started, Jared suggests we walk to a café. A good hour of our conversation is all but drowned out by the sonic dissonance of coffee machine and local pop-music radio station. A second hour, spent back at Atlantic House, is differently undermined by the space Jared puts between us (his studio is generous in its proportions, any sounds at once brittle and oddly diffused in its double volume). If Jared’s vocation is the obscuring of the voice, mine is its antonym. He slyly evades my ambitions; I slyly work against his. Even as he walks across to the room to deliver a phrase to the far wall, seemingly out of earshot of my listening phone, I know I will find it in the rustling static, emerging as his images emerge from otherwise undefined fields of eclipsing pigment.

L.B. As a way of beginning, I want to ask you what can and can’t be known. Inhabiting unknowingness seems to me an essential part of your practice – how do you productively undermine any certainty you may develop over time? Or is the certainty simply knowing that if you wander in a given direction, you’ll find your way?

J.G. I was thinking about this just yesterday. It occurred to me that there is really only a part of what I do that I can know, and another, larger part that I cannot know. During the making, I do come to peek inside that second part, but I can’t seem to bring any of that knowledge back with me. I don’t believe it’s possible to.

I’ve had some hidden ambition to be a certain way, a certain kind of artist, an aspiration to be like the people I admire – and yet no matter how much I’d like to be that way and make that kind of thing, I really can’t seem to help but do this other thing. It’s impossible not to do my thing. I feel a kind of piety toward my practice in the way that there is an intuitive ethic of making.

Only recently have I realised how much time I spend alone, and how unusual that is. And it did make me wonder if the work is just a result of a temporary madness experienced each day in this chosen solitude. Rummaging around and pursuing these little quests, depicting things on canvas, rubbing them out, becoming very involved and attached and embedded in these material experiments.

In the end, I go into the studio to do something, moved by some kind of question of ‘what if’, and then things happen. Later, I look back and see if there is anything meaningful to me, or resonant, that feels honest.

L.B. How do you measure that, that honesty? How do you know, to your satisfaction, that you tried? That you tried and that the thing has integrity?

J.G. I know if it’s an honest line or a contrived line because they come from different places. I’m open to the possibility that one kind of line, the honest kind, will be legible within a community – or at least, that lines are legible. That we can read them much like we have an ear for someone who is fibbing. To some degree, that is what I’m testing.

I don’t yet have a very sophisticated language for it, but I look at my daughter’s line, a child’s line, and it so clearly carries a beauty. We all see it. We see the honest pursuit, the curiosity in the material. A desire to describe the world that is attentive and responsive to feedback.

L.B. A complete unconsciousness of the line. This perhaps calls back to what I said earlier, my sense of slippery certainty in your work – you know what you’re looking for, but at the same time, you can’t over-determine your mark-making.

J.G. It is so genuinely frustrating, this tension. I develop strategies, but the strategies fail. There has to be real and total abandonment of any sort of intended value to the line for it to function.

L.B. Maybe that’s why writing about your work, as you’ve previously expressed to me, feels antithetical to the labour of its making. There’s a finished quality to a sentence.

J.G. The fixedness of writing doesn’t help me, and I don’t like my voice. Perhaps that’s more the issue.

I don’t like this voice, the voice that speaks, which I know is common. I also don’t like my written voice, except for my love letters. But mostly when I look back at old work, I don’t mind the voice. Essentially, I’ve found a way to make my utterances that is always ambiguous.

I’m terrified by the fixedness of writing because I fear being misunderstood. But it’s not only that – it’s also that I change my mind a lot.

L.B. There is that rare species of artists whose work arrives in the world with its writing, all very contained. But I find that most other artists work in wordlessness. They may not be able to speak to their work directly, but when you present them with a text, they have a strong sense that it’s precisely wrong. The writer has to work in that way, presenting them with interpretations, learning about the work by what it isn’t. Artists are so sure in their rebuttals.

J.G. I agree with that. If someone makes an assertion, I am certain in my response.

This is how what I do appears to me: I arrive at the studio. There are things on the go, and I continue pursuing those things. I don’t really talk about them with anyone. It’s just a private engagement and chaotic relationship to whatever’s going on, and I can only hope that, as I near the point when it’s necessary to know what’s happening, I’ll reach some kind of clarity. And thankfully, most often, I do. I’ll think, This is what’s going to happen, I’ll call the show this, and there’ll be a painting of a horse. I’m seeing it like this, and this is the group of work, this is the body. I’ll say all this to someone, go home and have a sleepless night, and wake up thinking, This is bullshit – then call the gallerist and say, Forget everything I told you. I’m telling you this because for me there’s something interesting and necessary at the moment of publishing- and exhibition-making. And by publishing, I might simply mean sharing my thoughts with someone. Only at that point can I get some critical distance from the work – and then I go back in. I make another arrangement.

L.B. When you say ‘make another arrangement’, do you mean you might pull out works and add others? Or that you conceive of the whole differently?

J.G. Both. This work is out; that’s out. This whole notion is out; this whole logic, out. New plan.

L.B. But then the logic wasn’t necessarily there to begin with.

J.G. No, no, it was – but it’s a logic I feel happy to discard.

Can I tell you how I make paintings? Incidentally, I didn’t initially set out to make them. I first made some soft sculptures out of canvas with a sewing machine and stuffing.

So I had leftover canvas. Then I had some wall paint leftover from painting my studio. I don’t precisely remember when I stretched the canvas onto the wall, but I did. For my exhibition Interludes at blank projects in 2017, I had thought, I’m going to build a theatre. It’s going to capitalise on all sorts of activities. I can make backdrops, and I can make sculptures that are the players. I can make a soundscape for the theatre. All this making will be bound by this logic and propelled by this question: can I make a theatre in a gallery? (The answer is no, by the way, you can’t. It necessarily returns to an art object, flattened by the white cube of the gallery.)

But before I came to this realisation, I made at least six huge backdrops that could be rolled up and unrolled during the various scenes.

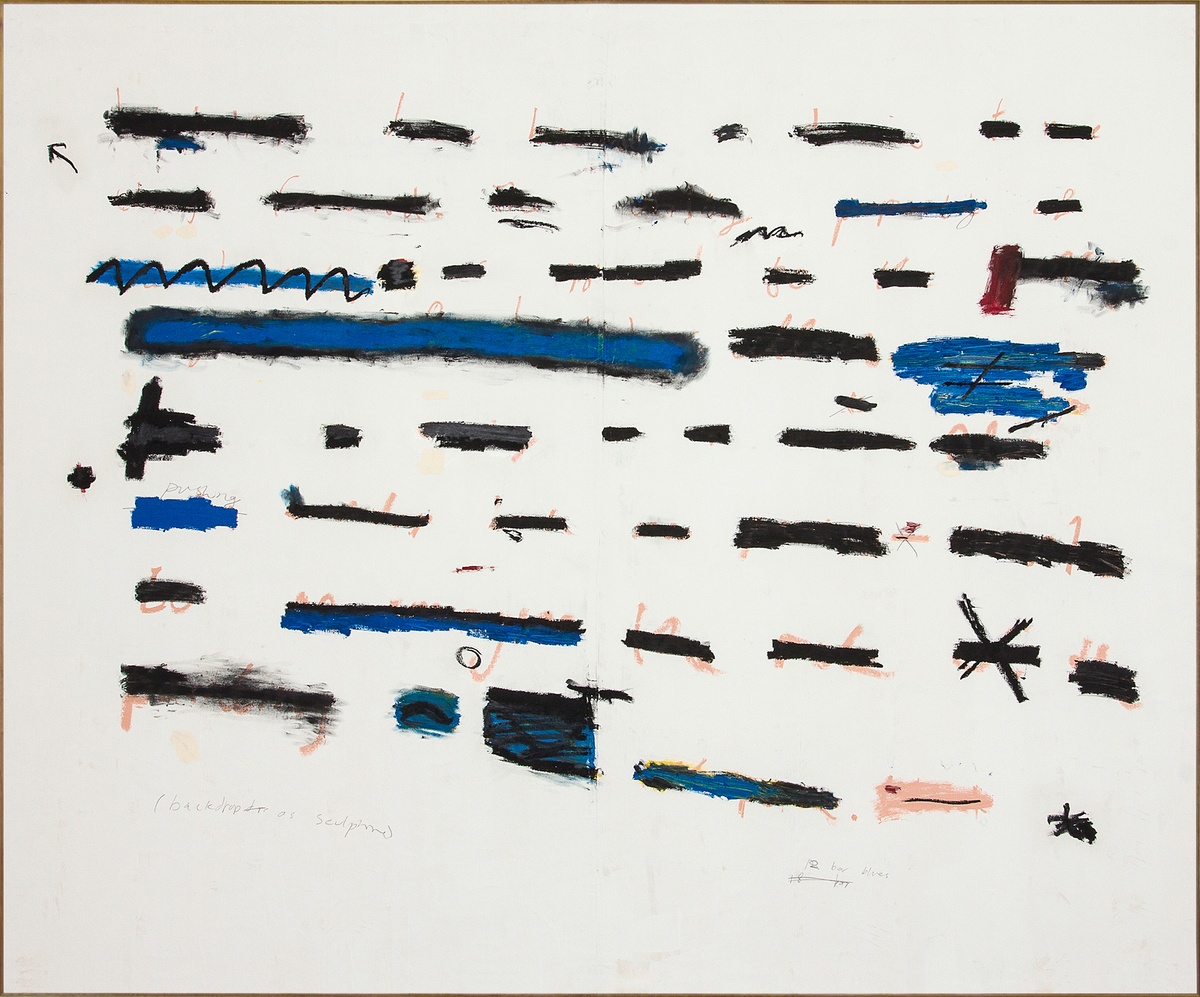

I had used the canvas stretched on the walls as large notepads. I was making notes around the making of the theatre, writing onto the canvas, often in big paint sticks or pencil, whatever I had on hand. There was a feedback loop going on. The making was instigating ideas around the making that were then being recorded as notes, guiding the making.

At a point, the text would be obliterated, redacted, concealed – and this kicked off an act of composing and balancing. These paintings were useful in different ways. They were backdrops, yes, but also very effective studio tools.

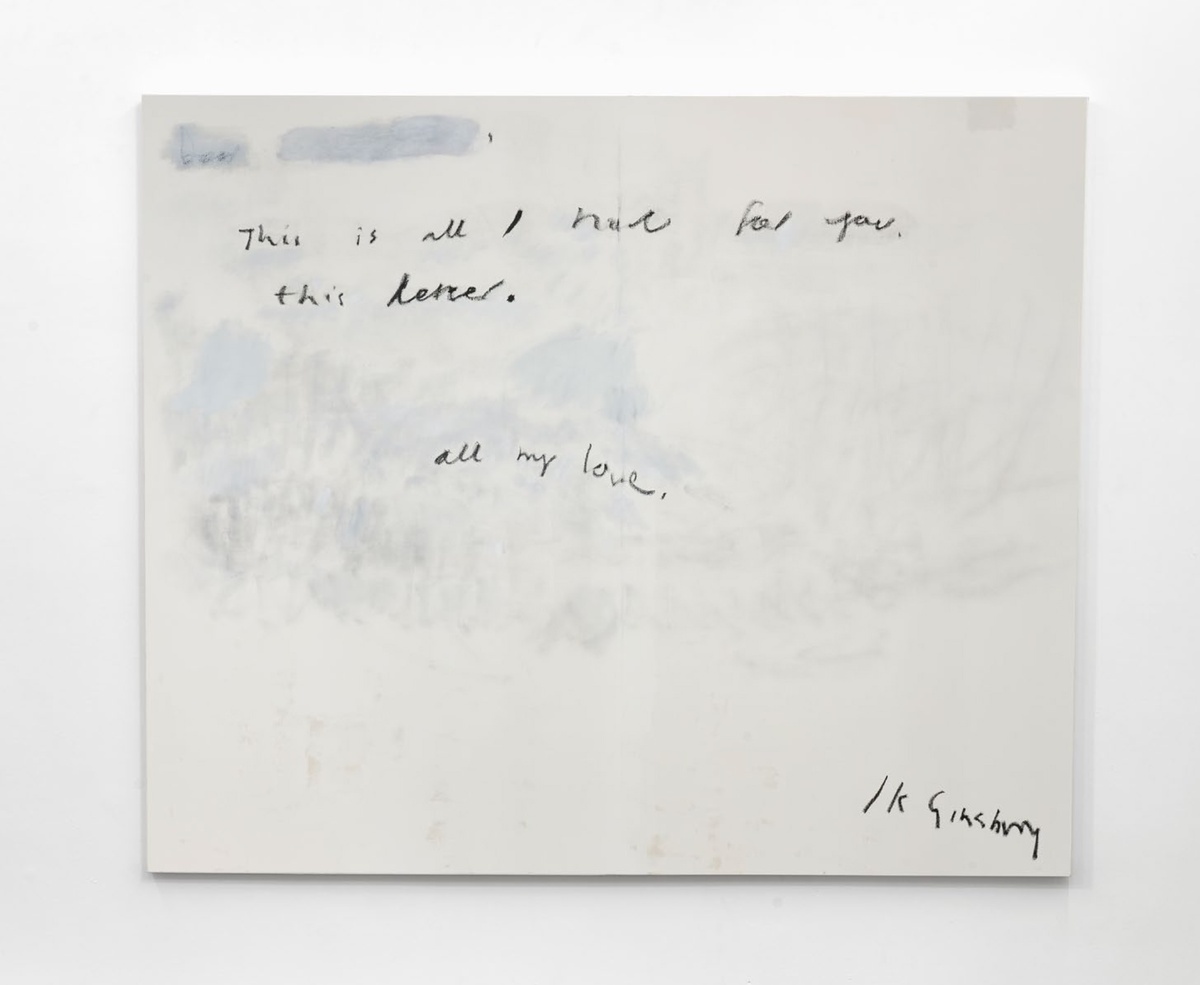

My gallerist later suggested we stretch these works; we tried one, and loved how it transformed. Imagine these scruffy canvases now stretched around a frame, all sharpened up. I thought, Okay, cool, I know how to do this now. But then I didn’t make another painting for two years because I didn’t have the analogue – I didn’t have the need for a backdrop, and it was so frustrating. I wanted to be catalysed into making paintings again, but I couldn’t find a way in, a good reason. Then Covid came, and everyone was feeling so disconnected, and I decided to write letters to people close to me. The first letter was to Jonathan, my gallerist. It went, Dear Jonathan, this is all I have for you, this letter. All my love, Jared. It was very sincere. I felt bad because I had committed to do a show, and this was all I had. An enormous letter, three metres high.

I later realised that these letters were not only a way to make paintings, but an excuse to express love to various people in my life. The most important thing that was being conveyed in this work was the only thing that needs to be conveyed in any exchange between two humans – an exchange of love, all of it, all my love.

Here’s a completely useless message – This letter is all I have – and it’s a lie, because what I’ve given you in the letter is everything. I really liked that.

Now, when I make paintings, I don’t call them other things. After ‘backdrops’, they were ‘letters’ and later ‘postcards’. Now I’m out of the closet – I make paintings.

I still go about making them in exactly the same way. I use the surfaces as places to write.

The writing is big and slow. It’s not a recording of a thought. Instead, it’s as if the thought is built. And because the writing is slow, because the surface is big, you have more time to get it right. And there’s absolutely no consequence to it, because it’s always going to be somehow obscured.

Later, I try to cover it up as best as I can – and then I wait for things to happen, for something to come from the thing. Here is A fine picture of a horse. I saw the horse and I painted it in.

Recently, I’ve been using a lot more colour. When colours are laid on top of each other, there’s so much complexity in their collision, in their relationship. This ground becomes extremely fertile for a different category of thing to emerge.

L.B. There’s the line that inscribes or describes – your letters and notes, any figurative drawings – and then there’s something of the inverse happening in these colour works.

J.G. When I'm making a painting, there are sections I naturally become attached to. It could be a certain blue because of its proximity to that red and that pink – an amazing setup of that blue, you’ve never seen such a nice blue. I worry sometimes about how permissible it is to care about such inconsequential things. At that point, the community that cares about them is limited to one person – me; no one else cares for it. When it’s declared finished, for example, as a painting, it’s then expected to enter into a greater economy of care, where someone beyond me could care about it, become attached to it or value it. But during the making, there are these points of value known only to me – a private economy of care.

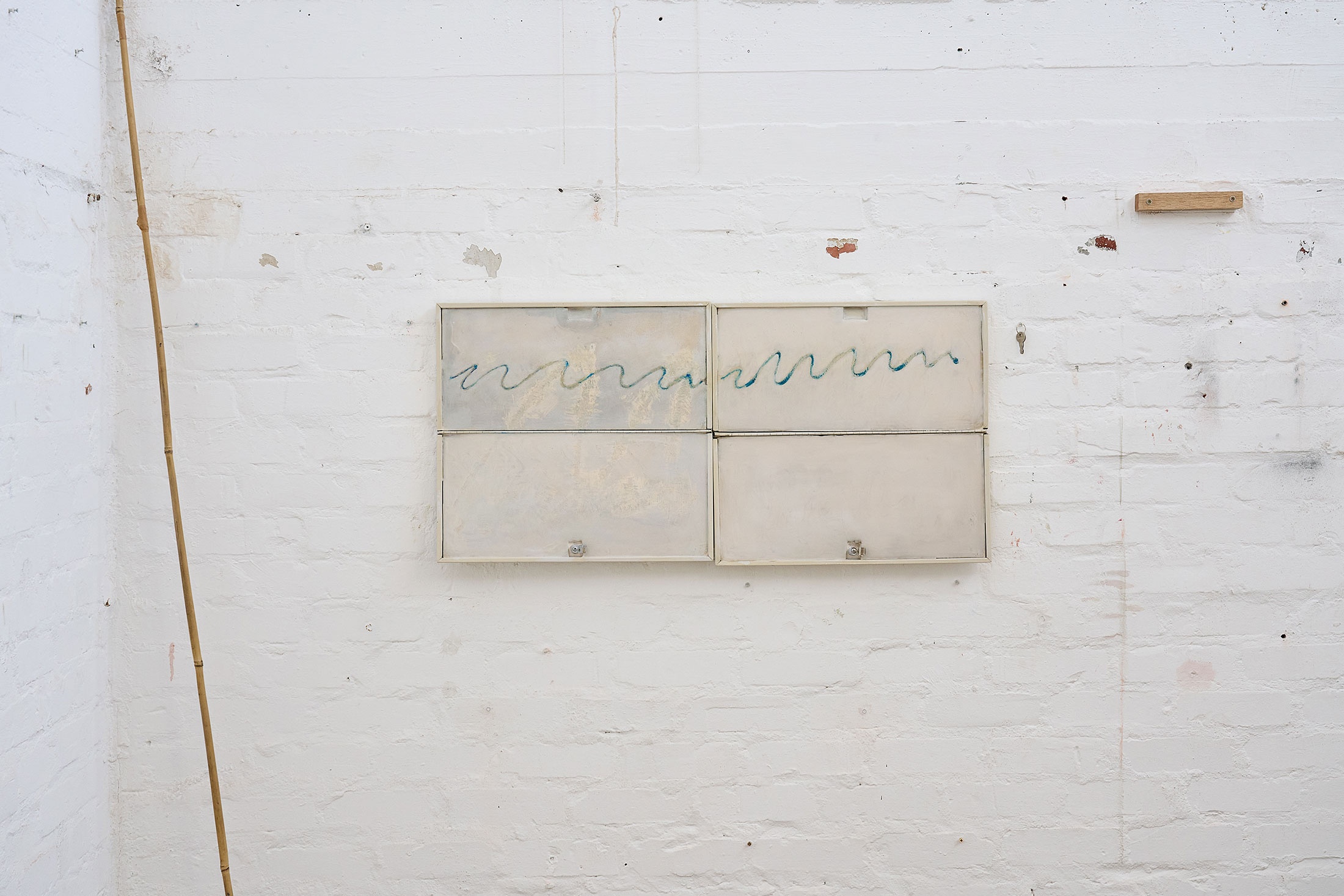

This reminds me of the cases I make for objects. There’s something fun and funny about taking a thing and making a literal case for it. That thing is suddenly being cared for. When I’m making a setting for a piece of bamboo, say, I’m forced to sympathise with the object, because I want to make a bed for it, and it must be soft. Suddenly, I have to be very attentive to this object, and by the end of the process, I almost always end up very attached to it.

L.B. So even if the thing didn’t initially resonate with you, you fabricate a resonance in the care with which you consider it?

J.G. Yes, I literally fabricate it – and it becomes real. Genuine. It often happens when I test things. I’m like, I’m not sure how to do this. I’m going to use something not precious to begin with, to test this idea, a scrap of wood – but by the time I’m finished, that’s the thing; I love this thing. Take anything, make its own little box, watch how our relationship to it changes.

L.B. Let’s return to the new colour paintings, which seem so different to your usually spare palette.

J.G. I’ve become so curious about colour and more confident in – there was a time when I wouldn’t have been able to have a conversation about colour. I had no experience with it, and so no relationship to it. But I’ve been interested in it secretly, and I realised recently how shy I was about my enjoyment of colour, how careful I was not to talk about it, because I didn’t feel any authority to discuss it. I felt that other people who dealt with it understood it in a way I didn’t.

L.B. Do your colour paintings also begin with writing?

J.G. They all do. Well, there are a few instances where they begin as drawings, and the drawings are enough, so I stop there. The writing serves two purposes: to record thoughts and to build thoughts, but also to make a problem that needs addressing. I’ve never let anyone actually read these things, but let’s see… This note says, “In the maroon painting that was turned into light blue, I realised I required a green in the top left.” The text was one honest way to put down colour. I had this feeling that a green bit within this blue section might resolve things. But now I can’t just put that colour there – and this is where it gets a little bit weird. Why can’t I do that? I don’t know why. But when I next have a thought that needs recording, I will take the colour and use it to write with, knowing that those marks will be true.

L.B. There’s something about intention and the arbitrary... the elaborate ruse.

J.G. Well, the problem can be fake, but the solution must be real.

Here it says, “True act to honestly attempt to conceal.” Okay, so that’s important, because I can get caught up in the naturally expressive part of this activity. But if I remind myself to just focus on the real attempt to conceal the text, then I’ll have a perfectly fine relationship with the residue, the result.

That’s the primary question in all this: how do I maintain this relationship to the acts, the actions? Is there a usefulness to it? Yes? Then it’s worth pursuing.

L.B. Even if its use is obscure even to you.

J.G. Yes, it’s the ladder – the ladder that you use to get to the thing, and then you can discard the ladder. The usefulness might only be a propulsion into another state or space. I need to know why I’m making the marks I make; they can’t just be flourishes.

Sometimes I hear painters talk about the process of painting and how they find solace in it. I don’t have that at all, but I really like solving a painting – winning them, like an argument.

L.B. Until that moment, does the activity feel quite punishing?

J.G. It feels unsettling. I don’t like that feeling, but then again, I’m quite happy to have something to do. I know what the task is. Continue, continue, continue.

There’s a blank canvas, and then for one reason or another, I end up marking it with text or a drawing, a sketch for a sculpture, whatever. And now the canvas is not empty. Now I’ve kicked off a conversation.

There’s an energy exchange; it’s asking something of me, though I’m never sure what. Over time, I try a few things, make the problem even bigger, feel lost. In the end, if I am lucky, it stops asking something of me and begins to return something. That’s the point I must be open to.

Here’s an example – a painting that felt weird and foreign. It was a perfectly fine painting, but it was disturbing, overworked. Eventually, it was just so weird that I had to hide it around the corner. Then one day, I dragged it back into the arena and, with a big brush, blocked out all the information of the image, returning it to zero. As I walked off, going to wash my hands, I looked back, and – I don’t think I’ve ever felt this way about a thing I’ve made. I just had this admiration for it. There was this moment of blue, a little section that the whole work was supporting. And I loved it.

I select particular paintings to be exhibited because they resonate with me in a way that I can’t deny, and I feel compelled to see how they operate in the world. I have to reveal or put forward the object; the results of this experiment need to be shared.

L.B. The work demands a life beyond you.

J.G. That’s when I start to learn things about the work in a new way. All of a sudden, I’m standing here with you, looking at the palette, looking at the connections. Thinking, Look, you’ve drawn another pair of legs. A figure, a foot, a face – how good we are at discerning ourselves in abstraction.

Here’s another note you might appreciate. It says: “A line is a sentence.” And like writing, if the line is made in a way that it is truly descriptive, it will likely have a rhythm to it. There’s a particular syntax to a good, honest line.